Patients who are paralyzed usually have to be catheterized, eroding their quality of life and placing an additional burden on their caretakers.

Catheterization leads to infections and other complications, and it doesn’t entirely eliminate accidents. The only way to definitively prevent them is with surgery that slashes the dorsal nerve — and destroys all sexual response. The options aren’t good.

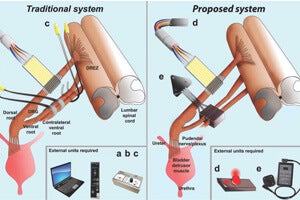

But a study published recently in Science Translational Medicine suggests that it may be possible to give paralyzed patients control over their bladders while avoiding both catheterization and the nerve-slashing surgery. Instead, doctors could craft insulated packets of nerves and connect them to an electrical probe that allows patients to urinate with the touch of a button, according to the study.

But a study published recently in Science Translational Medicine suggests that it may be possible to give paralyzed patients control over their bladders while avoiding both catheterization and the nerve-slashing surgery. Instead, doctors could craft insulated packets of nerves and connect them to an electrical probe that allows patients to urinate with the touch of a button, according to the study.

In proof-of-concept surgery performed on 50 rats, lead author Daniel Chew, of the University of Cambridge Center for Brain Repair, connected packets of nerves to the bladder and to an electric probe. The device could detect and override nerves firing to signal that the bladder was filling.

If the bladder became full enough to potentially empty on its own, the electrical device emitted a signal that overrode that signal and kept the bladder from contracting. But when a button was pressed on a portable device connected to the internal probe, it magnified the full signal, telling the bladder it was time to go.

“This work opens a new avenue for the design of a neuroprosthesis for bladder control after spinal cord injury,” the journal editors wrote of Chew’s efforts.

Many other neuroprosthetic man-machine interfaces have been proposed to help the paralyzed. The field has expanded in recent years, thanks largely to the hundreds of millions of grant dollars distributed by the Christopher and Dana Reeve Foundation. The University of Cambridge Center for Brain Repair is one of many research centers to receive such funding.

According to the Reeve Foundation, 1 in 50 Americans suffers from paralysis of some sort. (Similar global data is not readily available.)

According to the Reeve Foundation, 1 in 50 Americans suffers from paralysis of some sort. (Similar global data is not readily available.)

But the developments have been limited to “few but impressive clinical successes, and multiple breakthroughs in animal models,” according to an overview of the field published alongside Chew’s paper.

In one major clinical success, a paralyzed man walked again with the help of an electrical implant. In another success, rewiring nerves in the arm of a paralyzed man allowed him to regain some basic use of his hands.

Robotic exoskeletons are also being developed to help paralyzed patients.

Photos: Steven Frame via Shutterstock.com, Chew et al via Science Translational Medicine