Blindness might just be the first major disability to disappear, at least if our high-tech future takes more a utopian than dystopian bent. A bionic eye is already on the market in the United States, and stem cell therapy has been shown to restore sight in mice. Now British scientists have successfully printed retinal cells.

Researchers have used 3D printing — an essential part of the effort to produce viable tissue and organs to replace what is damaged — with body cells before, but the process is more successful with some types of cells than others.

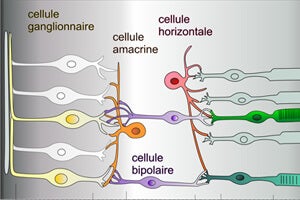

In the study, adult retinal ganglion and glial cells of rats were printed using a piezoelectric printer. Most cells emerged undamaged, and the researchers were able to culture the printed cells as successfully as they did cells that had not gone through the printer. Of the cells that first appeared lost in the process, most turned out to be clinging to the printer head.

The Cambridge researchers, Barbara Lorber and Keith Martin, took on a kind of worst-case scenario, using fragile adult cells rather than hardier embryonic cells and a harsher piezoelectric printer rather than its more commonly used cousin, the thermal inkjet.

Glial cells, properly part of the nervous system, are important to study as part of regenerative approaches to blindness because, when activated following injury, they release growth factors that help rewire the connection between the ganglia and the optic nerve, according to the study.

One key test for a printing approach to eye repair is whether cones and rods can also be printed, and the Cambridge researchers will turn their attention to that next.

One key test for a printing approach to eye repair is whether cones and rods can also be printed, and the Cambridge researchers will turn their attention to that next.

If they succeed, “printing of a functional retina for the cure of some forms of blindness could be within reach,” they conclude. Even if it proves out of reach, printing the ganglion and glial cells in their normal anatomical structure would allow researchers to further study how cells proliferate and how drug treatments affect the retina.

Images: Sergey Nivens via Shutterstock.com; Pancrat via Wikimedia Commons; RepRap; cover photo Dzenanz via Wikimedia Commons