New Inexpensive Skin Test in Development to Diagnose Malaria in an Instant

Efforts to devise better, cheaper tests are nothing new, but Rice University researcher Dmitri Lapotko has developed the first bloodless, instant test for the disease. According to a recent paper in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, Lapotko's test is accurate enough to detect a single infected red blood cell in 800 with no false positives.

Share

Malaria is a disease untamed by modern medicine. There’s no vaccine; tests are slow and inaccurate. The disease, meanwhile, kills with terrifying efficiency, sometimes in as little as 24 hours. Hundreds of millions of people fall ill with malaria every year, and roughly 600,000 die.

Efforts to devise better, cheaper tests are nothing new, but Rice University researcher Dmitri Lapotko has developed the first bloodless, instant test for the disease. According to a recent paper in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, Lapotko's test is accurate enough to detect a single infected red blood cell in 800 with no false positives.

“Ours is the first through-the-skin method that’s been shown to rapidly and accurately detect malaria in seconds without the use of blood sampling or reagents,” said Lapotko.

Researchers have just begun testing the new method on human patients.

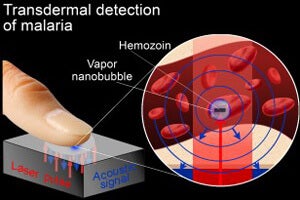

Here’s how it works. A laser burst through the skin of the ear or finger heats the hemozoin iron crystals that malaria parasites carry as a byproduct of digesting hemoglobin. The heating hemozoin creates a tiny bubble, which eventually pops. The test identifies the visual and acoustic signatures of that pop. (Because the popping bubble only occurs as a result of laser stimulation, there are, researchers say, no false positives.)

The method — dubbed hemozoin-induced vapor nanobubbles, or H-VNB — successfully identified mice with just 0.00034 percent of their cells infected with malaria, Lapotko reported in PNAS. Infected human blood cells were also successfully detected in vitro.

Be Part of the Future

Sign up to receive top stories about groundbreaking technologies and visionary thinkers from SingularityHub.

The laser seemed to cause no pain to the mice or damage to their ears, and when tested on human ears, it also appeared safe and painless.

The benefits over previous testing methods are marked. Because no medical personnel are required to perform the test, it would be more accessible to more people, and it gives instant results. It appears less likely than current tests to be deceived by the low malaria loads that mark the early stages of the disease. And it can detect the malaria parasite at any point in its lifespan in its host, another cause of potentially deadly false negatives.

The total cost per test would be roughly 50 cents. The laser is tough enough to withstand harsh conditions — such as those in semi-rural Africa and Latin America, where malaria is most common — with little maintenance. It can even run on a car battery.

If the H-VNB method works on humans as well as it worked on mice, it may bring instant, accurate malaria tests to hundreds of thousands of people.

Images: CDC via Wikimedia Commons, Dmitri Lapotko

Cameron received degrees in Comparative Literature from Princeton and Cornell universities. He has worked at Mother Jones, SFGate and IDG News Service and been published in California Lawyer and SF Weekly. He lives, predictably, in SF.

Related Articles

This Week’s Awesome Tech Stories From Around the Web (Through December 20)

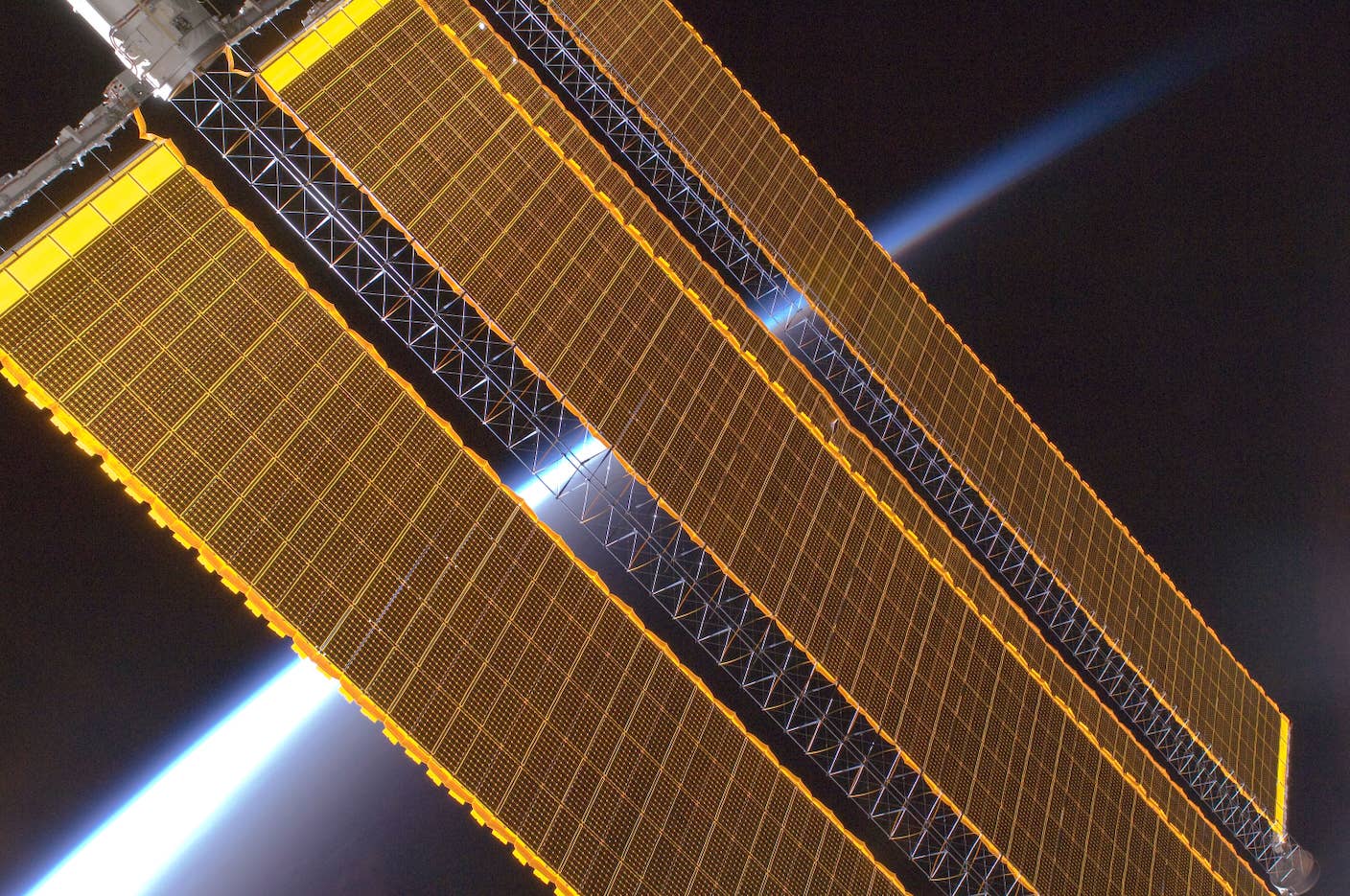

Data Centers in Space: Will 2027 Really Be the Year AI Goes to Orbit?

New Gene Drive Stops the Spread of Malaria—Without Killing Any Mosquitoes

What we’re reading