How to Plan a Revolution (an Excerpt from Abundance)

Share

How did a simple Facebook group mobilize 12 million people in 40 countries in just one month?

That's exactly what Oscar Morales accomplished when, in 2008, he created a Facebook group called A Million Voices Against FARC.

I wrote about his story in Abundance -- the excerpt follows.

You've heard me say that technology is a resource-liberating force, check out the human-resources liberated by this!

One Million Voices, an excerpt from Abundance

In 2004, while doing graduate work as a Rhodes scholar at Oxford University, Jared Cohen decided that he wanted to visit Iran. Since Iran's stance against the United States is based partially on US support of Israel, Cohen -- a Jewish American -- didn't think he stood much chance of getting a visa. His friends told him not to bother applying. Experts told him he was wasting his time. But after four months and sixteen trips to the Iranian Embassy in London, he received permission to travel to, as Cohen later recounted in his book Children of Jihad: A Young American's Travels Among the Youth of the Middle East, "a country that President Bush had less than two years ago labeled as one of the three members of the 'axis of evil.'"

The purpose of Cohen's trip was to expand his knowledge of international relations. He wanted to interview opposition leaders, government officials, and other reformers, but after successful conversations with the Iranian vice president and several members of the opposition, the government's Revolutionary Guard sauntered into his hotel room late one night, found his potential interview list, and foiled his plans. But rather than leaving Iran and flying back to England defeated, Cohen decided to explore the country and see what kinds of friends he made along the way.

He made plenty of friends, most of them young. Two-thirds of Iran is under the age of thirty. Cohen dubbed them "the real opposition," a massive, not-especially-dogmatic youth movement hungry for Western culture and suffocating under the current regime. He also discovered that technology was allowing this movement to flourish -- a lesson that crystallized for him at a busy intersection in downtown Shiraz, where Cohen noticed a half dozen teens and twentysomethings leaning up against the sides of buildings, staring at their cell phones.

He asked one boy what was going on and was told this was the spot everyone came to use Bluetooth to connect to the Internet.

"Aren't you worried?" asked Cohen. "You're doing this out in the open. Aren't you worried you might get caught?"

The boy shook his head no. "Nobody over thirty knows what Bluetooth is."

That was when it hit him: the digital divide had become the generation gap, and this, Cohen realized, opened a window of opportunity. In countries where free speech was wishful thinking, folks with basic technological savvy suddenly had access to a private communication network. As people under thirty constitute a majority in the Muslim world, Cohen came to believe that technology could help them nurture an identity not based on radical violence.

These ideas found a welcome home in the US State Department. When Cohen was twenty-four years old, then Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice hired him as the youngest member of her policy planning staff. He was still on her staff a few years later when strange reports about massive anti-FARC protests started trickling in. The FARC, or Revolutionary Armed Force of Colombia, a forty-year-old Colombia-based Marxist-Leninist insurgency group, had long made its living on terrorism, drugs, arms dealing, and kidnapping. Bridges were blown up, planes were blown up, towns were shot to hell. Between 1999 and 2007, the FARC controlled 40 percent of Colombia. Hostage taking had become so common that by early 2008, seven hundred people were being held, including Colombian presidential candidate Íngrid Betancourt -- who'd been kidnapped during the 2002 campaign. But suddenly, and seemingly out of nowhere, on February 5, 2008, in cities all over the world, twelve million people poured into the streets, protesting the rebels and demanding the release of hostages.

Nobody at State quite understood what was going on. The protestors appeared spontaneously. They appeared to be leaderless. But the gathering seemed to have been somehow coordinated through the Internet. Since Cohen was the youngest guy around -- the one who supposedly "spoke" technology -- he was told to figure it out. In trying to do that, Cohen discovered that a Colombian computer engineer named Oscar Morales might have been responsible. "So I cold-called the guy," recounts Cohen. "Hi. How are you? Can you tell me how you did this?"

What had Morales done to bring millions of people into the streets in a country where, for decades, anyone who said anything against the FARC wound up kidnapped or dead or worse? He'd created a Facebook group. He called it A Million Voices Against FARC. Across the page, he typed, in all capital letters, four simple pleas: "NO MORE KIDNAPPING, NO MORE LIES, NO MORE DEATH, NO MORE FARC."

"At the time, I didn't care if only five people joined me," said Morales. "What I really wanted to do was stand up and create a precedent: we young people are no longer tolerant of terrorism and kidnapping."

Be Part of the Future

Sign up to receive top stories about groundbreaking technologies and visionary thinkers from SingularityHub.

Morales finished building his Facebook page around three in the morning on January 4, 2008, then went to bed. When he woke up twelve hours later, the group had 1,500 members. A day later it was 4,000. By day three, 8,000. Then things got really exponential. At the end of the first week, he was up to 100,000 members. This was about the time that Morales and his friends decided that it was time to step out of the virtual world and into the real one.

Only one month later, with the help of 400,000 volunteers, A Million Voices mobilized some 12 million people in two hundred cities in forty countries, with 1.5 million taking to the streets of Bogotá alone. So much publicity was generated by these protests that news of them penetrated deep into FARC-held territory, where news didn't often penetrate. "When FARC soldiers heard about how many people were against them," says Cohen, "they realized the war had turned. As a result, there was a massive wave of demilitarization."

Cohen was fascinated. He flew down to Colombia to meet with Morales. What surprised him most was the structure of the organization. "Everything I saw had the structure of a real nongovernmental organization -- but there was no NGO. There was the Internet. You had followers instead of members, volunteers instead of paid staff. But this guy and his Facebook friends helped take down the FARC." For Cohen and the rest of the State Department, it was something of a watershed moment. "It was the first time we grasped the importance of social platforms like Facebook and the impact they could have on youth empowerment."

This was also about the time that Cohen decided technology needed to be a fundamental part of US foreign policy. He found willing allies in the Obama administration. Secretary of State Clinton had made the strategic use of technology, which she termed "twenty-first-century statecraft," a top priority. "We find ourselves living in a moment in human history when we have the potential to engage in these new and innovative forms of diplomacy," said Secretary Clinton, "and to also use them to help individuals empower their development."

Toward this end, Cohen had become increasingly concerned about the gap between local challenges in developing nations and the people who made the high-tech tools of the twenty-first century. So, wearing his State Department hat, he started bringing technology executives to the Middle East, primarily to Iraq. Among those invited were Twitter founder Jack Dorsey. Six months after that trip, when Iranian postelection protestors overran the streets of Tehran, and a government news blackout threatened all traditional lines of communication, Cohen called Dorsey and asked him to postpone a routine maintenance shutdown of the Twitter site. And the rest, as they say, is history.

Twitter, of course, soon became the only available pipeline to the outside world, and while the Twitter revolution didn't topple the Iranian government, in combination with Morales's efforts and other Internet-based activism campaigns, all of these events paved the way for what we would soon be calling the Arab Spring.

"It didn't happen intentionally," says Cohen. "Bluetooth was a technology invented so people could talk and drive -- nobody who built it expected their peer-to-peer network would be used to get around an oppressive regime. But the message of the events of the past few years are clear: modern information and communication technologies are the greatest tools for self-empowerment we've ever seen."

Please send your friends and family to AbundanceHub.com to sign up for these blogs -- this is all about surrounding yourself with abundance-minded thinkers. And if you want my personal coaching on these topics, consider joining my Abundance 360 membership program for entrepreneurs.

[Image credits: courtesy of diamandis.com and Shutterstock]

We are a participant in the Amazon Services LLC Associates Program, an affiliate advertising program designed to provide a means for us to earn fees by linking to Amazon.com and affiliated sites.

Diamandis is the founder and executive chairman of the XPRIZE Foundation, which leads the world in designing and operating large-scale incentive competitions. He is also the executive founder and director of Singularity University, a global learning and innovation community using exponential technologies to tackle the world’s biggest challenges and build a better future for all. As an entrepreneur, Diamandis has started over 20 companies in the areas of longevity, space, venture capital, and education. He is also co-founder of BOLD Capital Partners, a venture fund with $250M investing in exponential technologies. Diamandis is a New York Times Bestselling author of two books: Abundance and BOLD. He earned degrees in molecular genetics and aerospace engineering from MIT and holds an MD from Harvard Medical School. Peter’s favorite saying is “the best way to predict the future is to create it yourself.”

Related Articles

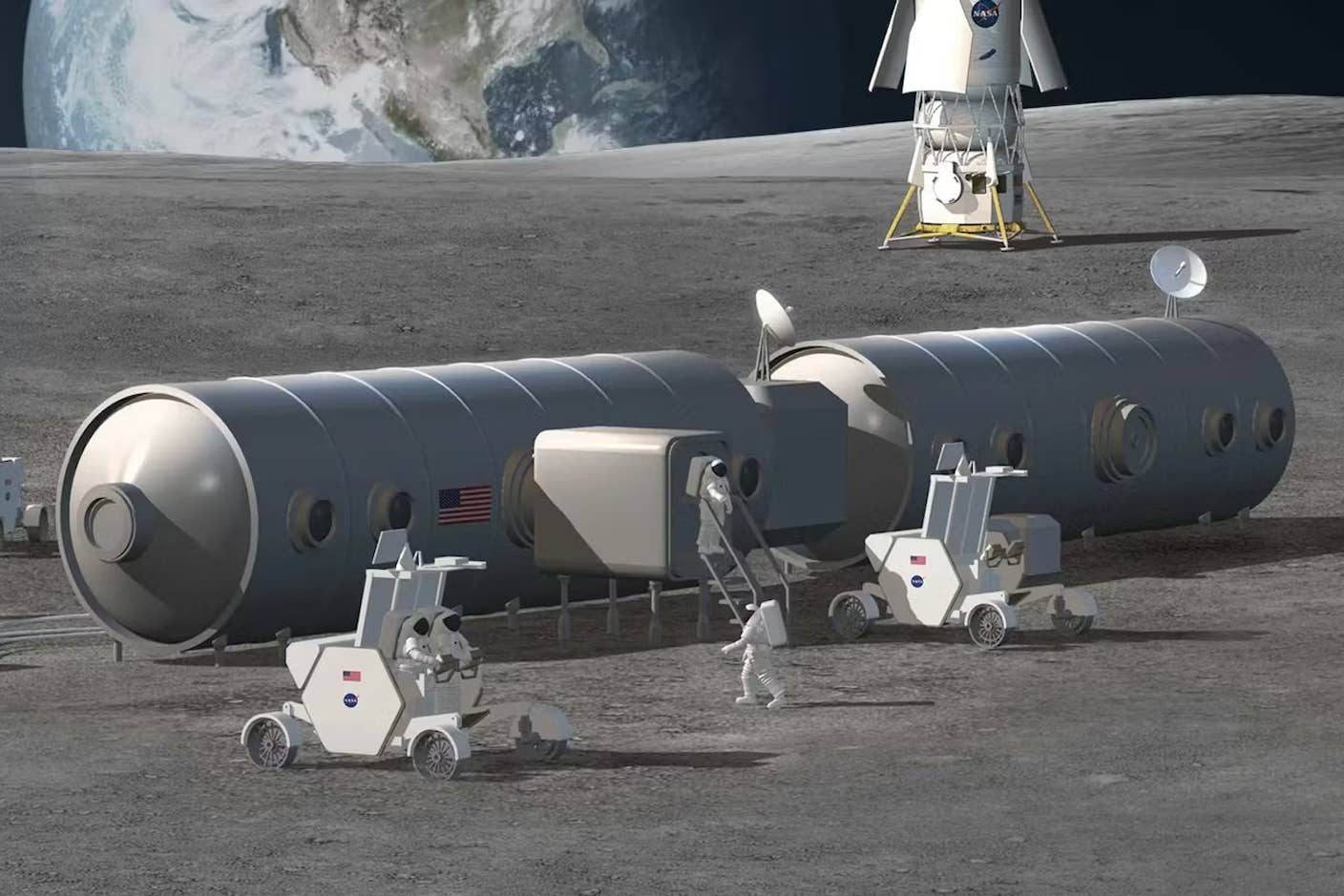

NASA Is Planning to Build a Permanent Moon Base by 2030. Here’s What It Will Take.

In a First, Researchers Use Stem Cells and Surgery to Treat Spina Bifida in the Womb

Hackers Are Automating Cyberattacks With AI. Defenders Are Using It to Fight Back.

What we’re reading