The Digitalization of Prosthetics Is Transforming How Wounded Service Members and Veterans Recover

Share

Sitting on Dr. Peter Liacouras’s desk is a razor, a stick of deodorant, and a partially built prosthetic arm. Behind him, several 3D printers buzz away, creating contraptions in plastic, nylon, and titanium. Today he is working on creating a custom device that will allow a wounded service member to get ready in the morning by themselves. We take it for granted, but this can be a daunting and consuming task for those who have lost a limb. As the director of service for the 3D Medical Applications Center at Walter Reed National Military Medical Center, Liacouras uses cutting-edge technologies to improve people’s quality of life by pushing the fields of prosthetics and orthotics forward.

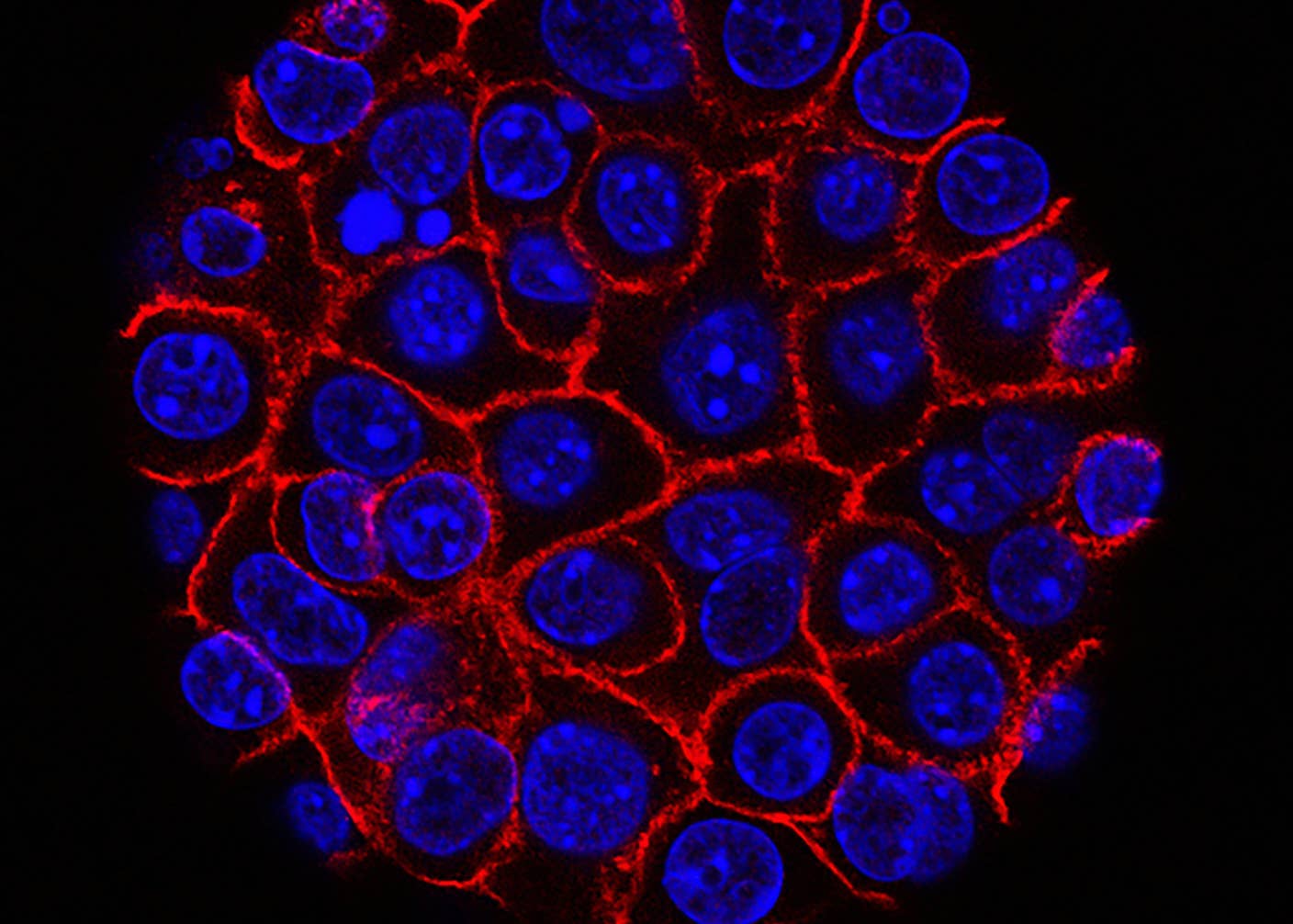

Image Credit: UNYQ

His goal is simple: to allow wounded service members to do the things that they used to do before getting injured. A provider recently asked if he would like to help an injured veteran play ice hockey again, and he gladly accepted. To do this he will have to study the biomechanics of the activity, examine how body weight shifts while skating, create anatomical models with a CT scanner, and then involve his whole team to brainstorm ways to give each individual patient the best possible outcome. As Liacouras detailed, these procedures allow for the creation of a customized treatment for each service member, “in amputee care we’ve created all sorts of different devices that allow them to go fishing again, rock climbing again, skating again, kayaking again. These are a different type of patient from the past; these are young, active patients that like to take part in complex activities. And this has really filled that gap of where normal prosthetics stop, and specialty prosthetics start.”

Two decades ago, much of this would not have been possible—the technology just wasn’t available. 3D printing, also known as “additive manufacturing,” has come a long way since Walter Reed first started experimenting with it in 2003. The printers themselves have become cheaper, faster, and better able to handle stronger materials. The technology’s adoption in healthcare has taken off. Batteries have gotten smaller, and equipment lighter. Even the components inside the prosthetics now include microprocessors and advanced sensors. But more important than the technology itself, it’s what has been done with it that has pushed the boundaries of what anyone thought was originally possible.

Image Credit: UNYQ

“The majority of our active duty patients this week are in Colorado skiing as part of their therapy,” Dave Laufer, the director of Orthotic & Prosthetic Services at the Department of Rehabilitation, proudly told me. He has seen the field of prosthetics change and grow over time from a manual, artisan process to one that is becoming inundated with technology. While some of this is “technology for technology’s sake,” when digital methods do work effectively they can be extremely helpful. At best, these tools can make prosthetics less apparent and more intuitive. Microprocessors in artificial knees, for example, have allowed the injured to stand with minimal effort—a game changer in the field. 3D printing can allow for prosthetics to be comfortable and symmetrical to existing limbs, which can play a major factor in whether people actually use them.

These advances mark what Laufer calls “an unintended good consequence from an unfortunate occurrence.” More Americans are returning home from combat having survived severe wounds and injuries than at any point in the past. Since the conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan began in 2001, there has been an unprecedented amount of focus and attention to the plight of the disabled. In the past, disagreements with Medicare and private insurance companies over what should be reimbursable had led to some stagnation. But recently, the US Department of Defense has bolstered the industry with their search to find optimal solutions for wounded service members. There are more than a million visits to Walter Reed every year; it’s one of the largest treatment centers in the country. Whatever new solutions are developed will have to thrive under its intense requirements.

Image Credit: UNYQ

Taken as a whole, this marks a fundamental shift in the way treatment is done from disability management to something more like a sports medicine model, where patients are treated like professional athletes. Army Captain Nicole Brown, officer-in-charge of the MATC, explained that the main goal for a service member used to be that they could “get around in a wheelchair all day, now we have goals of patients running in marathons.” Treatment is tailored to each patient’s personal needs and can be adjusted on a day-to-day basis depending on what the therapist sees. Advancements in surgical techniques have been helpful, but what continues to amaze her is the sheer will of the service members she treats—“their fortitude, their ability to keep going in the face of adversity…they don’t take no for an answer.” It’s the patients who are setting the terms of their care—they are showing the industry how far it can go by shattering the limits of what they were “supposed” to be able to do.

Be Part of the Future

Sign up to receive top stories about groundbreaking technologies and visionary thinkers from SingularityHub.

This transformation has opened the door for experts and entrepreneurs to contribute as well. Late last year, Walter Reed hosted a pilot study to test a new type of 3D printed prosthetic leg cover that is able to withstand tough physical conditions. The product was the result of a partnership between UNYQ—a San-Francisco-and-Seville-based startup that focuses on making prosthetics fashionable and functional, led by bionics pioneer Eythor Bender—and Medical Center Orthotics & Prosthetics—a Maryland-based Department of Defense contractor that collaborates with leading technology manufacturers to create solutions for highly active patients, led by Mark McVicker, who has spent 20 years working in the field. McVicker sees the leg covers as the start of a series of products that aim to streamline the processes of helping an amputee to recover.

More than just a physical product, the leg covers they introduced marked a breakthrough of sorts. To begin with, the process of fitting the patient for a prosthetic leg is done with UNYQ’s smartphone app. All that’s required is eight photos for an above knee amputee, and UNYQ is able to use photogrammetry software to create a CAD file that can go straight to the printer. What was once done by a team of people using their eyes can now be done more precisely by machine in minutes. Future versions of the product can be easily outfitted with sensors to collect information about how long its been worn, how its being used, and how it can be improved—which the company is already doing with their new line of award-winning scoliosis braces. (Watch Eythor Bender discuss prosthetics challenges and solutions below.)

To everyone’s detriment, the emotional and aesthetic aspects have long been ignored in prosthetics, according to Bender. He believes what’s required in the industry is a change in mindset, where personalization is understood to be just as significant as function. What the industry has produced so far has been cold and clinical, which greatly impacts how amputees feel about themselves. He hopes to do this by creating a digitized, repeatable process that can free up the time of doctors and clinicians so they can focus on their patients — as he puts it, “less worry about making the leg and more focus on getting people up and walking as fast as possible.” For the first time, recovering service members and veterans will be able to participate in the creative process of making their own prosthetic limbs by choosing the color, design, and materials.

What Bender and others innovating in the space are doing is creating choice where none existed before. The service members and veterans who have sacrificed their health and wellbeing for their country are once again showing us the strength of the human spirit and how far people can go when enabled by technology. Through perseverance, they are leading a complete change in how we process, handle, and understand disability that will improve lives for generations to come.

Banner Image Credit: UNYQ

I am a researcher with the Hybrid Reality Institute, and Co-Founder and COO of AIC Chile. Identified, a book I've authored about the global rise of digital identification systems, will be out later this year. It analyzes the impact of the technologies that governments and companies use to see who we are. I track these systems over time to see how they are changing governments, institutions, social norms, and your daily life. Learn more, and sign-up for updates here. Follow me on Twitter — @twadhwa — or check out my website for more articles, talks, and updates.

Related Articles

Autonomous AI Agents Have an Ethics Problem

Thousands of Everyday Drone Pilots Are Making a Google Street View From Above

These Supercharged Immune Cells Completely Eliminated Solid Tumors in Mice

What we’re reading