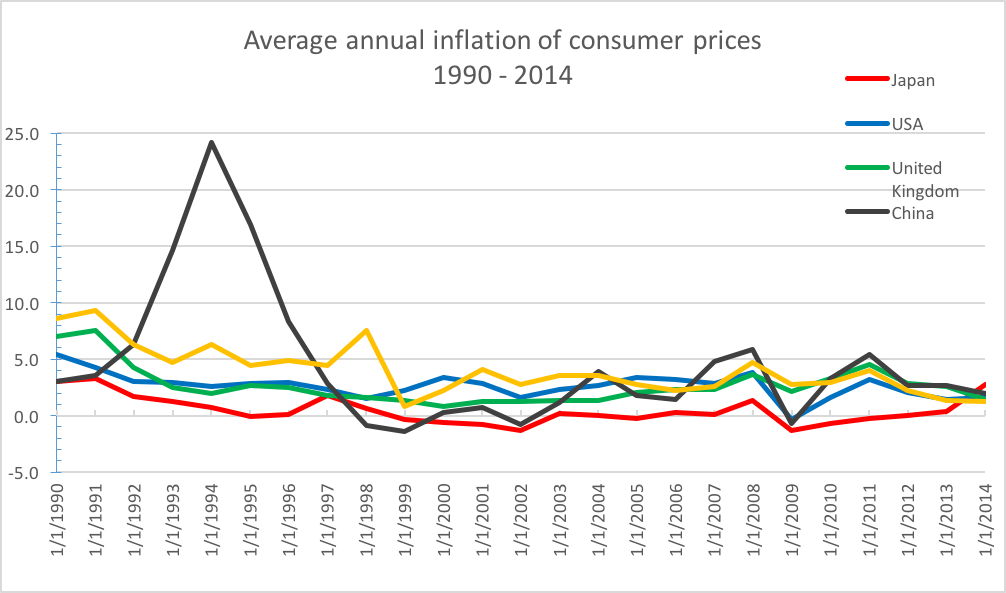

In the post-war years and into the 80s, no economy could match Japan’s for sheer speed and growth. Since then, however, Japan has struggled to overcome slower growth and stubborn deflation.

The country’s struggling economy even seems to be defeating Prime Minister Shinzo Abe’s once lauded ‘Abenomics’ stimulus program.

Worse still, there doesn’t seem to be a clear reason why the good ship Japan Inc. is listing.

One favored explanation is that Japanese consumers are clinging to every yen, fearful of the future. As a result, Japan’s companies and government get less revenue and taxes.

Some financial experts disagree. The issue, they say, is that Japan finds itself in the grips of a perfect, tech-generated storm. A situation made worse by central institutions failing to fully appreciate the magnitude of what is happening.

“Exponential technologies are disrupting industries, economies and central banks. It actually started decades ago,” says Brian Barnier who is head of research at ValueBridge Advisors.

“I see Japan’s economy as greatly influenced by these developments. In a lot of ways, the country is ahead of the curve, but the rest of the world is not far behind.”

If Barnier is correct, a rethink on the central economic doctrine and strategy followed by the world’s monetary powers—that deflation should be fought at all costs—is needed. Exponential technologies are simply too strong a deflationary force.

This not only applies to Japan, but to the whole world, which may be heading straight for the same choppy economic waters that Japan appears to be caught in.

Why (moderate) inflation = good and deflation = bad

A quick Econ 101 primer:

Steady inflation is considered a sign of a healthy economy. Imagine there isn’t enough of a product or service that people want. Historically, supply doesn’t shift much in the short run, so high demand equals rising prices. Inflation also means that money becomes worth less over time, which makes consumers spend and invest money now, rather than later.

Deflation is the opposite—and is nearly universally feared.

Initially, it might sound counterintuitive. Wouldn’t we rather pay less for stuff? However, why would we spend or invest a dollar today if it will buy more tomorrow? Deflation leads to falling investment and demand, making it hard for companies to sell their goods and pay workers—who in turn can’t buy anything. Sometimes we get deflationary cycles, which are thought to be self-reinforcing and difficult to break.

Welcome to Japan’s false nightmare

The Japanese government and central bank have been fighting deflation—and deflationary cycles—for many years.

The current government, under the leadership of Prime Minister Shinzo Abe, instigated a policy program commonly referred to as Abenomics. It involves three ‘arrows’ aimed at, among other things, creating jobs, stimulating economic growth and battling deflation.

For the government, it has involved large-scale investment in public construction projects and education, lowering corporate taxes and increasing the number of women workers. So far, the programs are falling somewhat short.

The Bank of Japan (BoJ) has been supporting the goals of Abenomics by trying to leverage monetary policies to generate a minimum 2% annual inflation—with rather limited success.

The situation is extra worrisome, as Japan faces many debt-related challenges.

Apples to apples

An explanation for Japan’s continued woes blames Japanese consumers. This view holds that they aren’t buying enough, including from Japanese companies, which has a negative effect on both the companies (who sell less) and the government (who gets less tax revenue).

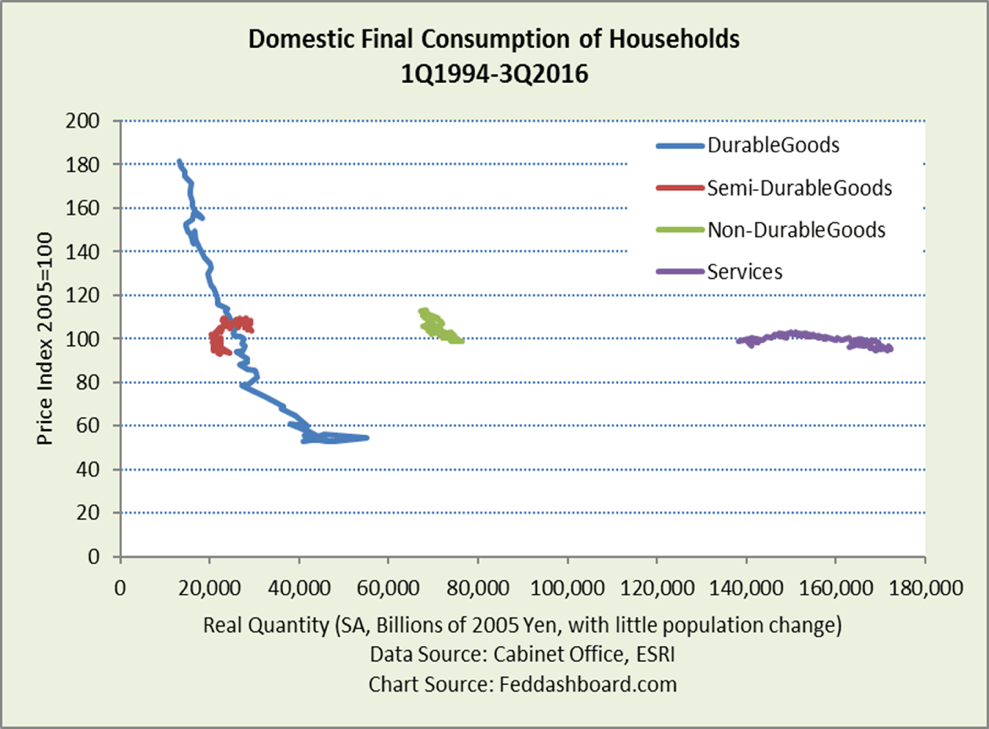

But Barnier, looking at Japanese economic data, finds evidence this assumption is wrong. The problem, he says, lies in the measures of economic growth (Gross Domestic Product or GDP) and inflation (Consumer Price Index or CPI).

GDP measures quantity of consumption and investment across households, non-profit organizations, government and business. CPI measures prices on a selected set of products for a selected set of consumers. Barnier argues both miss what is actually happening.

“It is a basic data science mistake, as the result is not an ‘apples-to-apples’ comparison,” he says.

“It’s more appropriate to use quantity and price for the same product category from the same shopper category, like for example domestic households and consumer durables such as tech, audio and video.”

Such a comparison shows that Japanese spending per consumer is actually strong.

In graph form (below), the data might look a little like an etch-a-sketch run amok. However, the squiggly lines, which represent how price and quantity move over time, show Japanese consumers have been buying more of especially durable goods (tech, audio, video, photographic, household appliances) and services as prices fall. In durables, Japanese consumers are actually buying more individual product units than their US peers.

In this video, Barnier explains a similar trend using animated US data to more clearly show these changes over time. As prices have been flat or have fallen dramatically over the last few decades in tech products, demand has continued to grow.

Technology at heart of mystery

So if consumers are buying more, why is it so hard to return Japan to the safe harbor of inflation? And why should you care? This is a problem, but just for Japan, right?

Not quite, says Barnier. Japan today is coming to where you live—and soon.

The reason? Effects from the sheer speed of technological development.

Intel’s computer chip from 1971 compared to its 2016 chip is a great illustration. Not long ago, Intel CEO Brian Krzanich said that a 1971 VW Beetle upgraded at the same speed would now have a top speed of about 300,000 mph, get 2 million miles per gallon of fuel—and cost you the staggering sum of 4 cents.

In relation to durable goods think of the price (and performance) of a 1994 camera compared to one from today. The drop in price is what we see in the blue line in the graph above. A development similar to what we have seen in many other industries in countries around the world.

Similar advances are evident in sensors, genomics, networking and telecommunications technologies, to name but a few. All these are technologies that drive many global industries—from manufacturing to finance.

Consumers are buying more, and an increasingly global market has so far helped offset the effect, but we are struggling to keep up.

In ‘What Technology Wants’ Kevin Kelly famously cataloged all the things in his house. His family alone turned out to own more things than most kings of England had ever owned. The rhetorical question then becomes, do we need all of those things? The point is that there is simply a limit for how many socks, phones, washing machines or even seriously souped up 1971 VW Beetles you can buy before it becomes gross, unnecessary overindulgence.

Abundance waves goodbye to inflation

Exponential technological development means we are heading from scarcity towards an economy of abundance. This in turn, means that economic theories and strategies that economists and governments have long used to track and regulate the economy are fast becoming outmoded.

The shift is profound. In essence, it means goodbye to the concept of scarcity, which has been a cornerstone of economic theory for the last 200 years. About time, you could argue, as these theories are based on assumptions formulated back when most people toiled in mines, fields and factories.

In this economic reality, many traditional measures and policies used to regulate a country’s economy have little—or only short-term—effect.

“It means that policies aimed at increasing purchases per shopper are misguided. For consumption, it’s almost all about population. For production, the need is for innovation. These are some of the lessons that Japan—as well as other countries—must heed if they are going to be ready for the future economy,” Barnier says.

Today Japan, Tomorrow the world

There are several reasons why Japan finds itself ahead of the curve. And why other countries need to take note of what is happening here (I live in Tokyo).

Part of the problem for Japan is that it has focused too strongly on management and quality control techniques taught by W. Edwards Deming. It is worsened by Japan’s Ministry of International Trade and Industry targeting growth in industries like electronics, automation and computing.

As a result, Japan has historically been chasing efficiencies (one of the core aspects taught by Deming) in industries where exponential technologies have led to massive price drops. In other words, many of the country’s biggest companies are in industries where the price per unit sold has been taking skydiving lessons since the 1970s and ’80s.

Another issue is that Japan needs to import masses of Barry White and Marvin Gaye CDs.

“It simply needs to convince its population to go home and make babies. The problem with Japan is not one of consumption, but consummation, as it were. More seriously, the rapidly aging population is an issue that Japan needs to find a solution to if it is to succeed in the 21st century,” Brian Barnier says.

He lauds the current government for its policies in this regard, as well as an increased focus on promoting innovation and critical thinking in education, which in turn helps grow startups, entrepreneurship and maker movements. All areas where Japan is currently lagging behind many other countries.

However, Japan is far from reaching safe ground yet.

To get there it needs to move on from BoJ policies like quantitative easing and accept that deflation or near-zero inflation will be the likely scenario in certain areas, like prices of durable goods. Secondly, Japan needs to measure prosperity not just in metrics like GDP, which hide the strength of individual consumers. Thirdly, the country needs to focus on how it can use technology to promote innovation and encourage innovation of “Japan, Inc.” over focusing on efficiencies of more recent years.

Since Japan is experiencing the early onset of economic changes that will soon affect the rest of the world, such changes would lead to a golden opportunity. The current economic and demographic difficulties can help lower the resistance barriers towards fundamental change. Although, it should be noted, Japan’s resistance barriers to change, can be very high.

Successfully abandoning the economic tools of the last couple centuries and picking up their 21st century equivalents will help prepare the country for the coming century of exponential change, as well as avoid wasting massive amounts of money trying to fight what seems like inevitable change.

All lessons which, like the economic effects of exponential technologies, apply to not just Japan, but most of the world—maybe apart from the ‘begatting’.

Image Credit: Shutterstock