New Virtual World Sansar Is Ready to Pick Up Where Second Life Left Off

Share

On its 14th birthday, a reflection on Linden Lab’s groundbreaking Second Life, and how their next project Sansar hopes to go even further.

In May 2006, Bloomberg’s Businessweek ran a cover story detailing the business empire of real estate millionaire Anshe Chung. What caught the world’s attention, however, is that Anshe Chung wasn’t a real person—she was an online avatar—and the properties she sold were computer-generated images rendered in the virtual world Second Life. It was the first time someone had generated such staggering real-world wealth by selling digital stuff in a virtual space.

Following the article’s publication, Second Life’s popularity exploded. The platform represented all that our future lives inside virtual worlds could be.

Users were able import virtual items, buy and sell virtual goods, design and personalize avatars, and hang out in nightclubs, shopping centers, and art galleries—each created by Second Life’s residents themselves. Major companies like IBM and American Apparel opened offices and stores, and Reuters even stationed a bureau chief to cover the virtual happenings there.

By October of 2006 the site welcomed its millionth citizen, and then millions more joined in 2007. But by 2008, the shine began to wear off, and user growth stopped.

A decade later, a common narrative is that Second Life, the “once massively hyped virtual world,” failed. That assessment, however, presumes that to be successful, it needed to take over the online world.

While Second Life never reached a level of mainstream adoption in the way a platform like Facebook has, it’s worth noting how groundbreaking it was—and still is today.

The in-world economy of Second Life, the one that supposedly 'failed' to take off, still outranks some small countries in gross domestic product.

“Last year [2016] the GDP of Second Life was half a billion dollars,” Ebbe Altberg, Linden Lab’s CEO, casually tells me while at their offices in San Francisco several weeks ago.

By that figure, the in-world economy of Second Life, the one that supposedly “failed” to take off, still outranks some small countries in gross domestic product. And for many users, operating a business there is still incredibly profitable.

“Users took home a collective income of $60 million last year,” Peter Gray, a senior spokesperson for Linden Lab, later tells me by phone. “Being a virtual landlord continues to be among the most financially successful businesses in Second Life. People are making money renting land, selling avatar fashion accessories, giving musical performances, providing services like hosting events, and for quite a few people, this is their primary source of income.”

Today, users are still logging in from almost every country on planet Earth, and clearly a vibrant world still hums there. There are approximately 800,000 monthly active users—only slightly down from a one-time peak of 1.1 million in 2007. That Second Life has maintained such a stable core of engaged users, despite never finding a way to continue their growth beyond 2008, remains one of the mysteries in the Second Life story.

A story which continues to add some fascinating anecdotes.

In one instance, researchers at Texas A&M designed a virtual chemistry lab and found that the virtual students there outperformed the real world students in certain tasks while also maintaining higher retention rates. In another, a user developed a series of stress-reducing environments so that Parkinson’s patients could virtually ice skate, dance, swim, and do other activities that might be difficult in the real world. And one user based in Amsterdam even re-created an entire historical replica of Berlin from the 1920s where daily happy hours and other social events still take place.

Even as Second Life remains active, Linden Lab is gearing up to release their next project—a social VR platform called Sansar—and they believe it could go beyond what Second Life was able to achieve and deliver on the promise of widespread use of virtual worlds.

Beyond Second Life: Sansar Is Ready to Take Off

Several weeks ago, I headed to the Linden Lab offices in San Francisco to get a demo and hear about the ways Sansar is taking a new approach.

When I arrived, Altberg brought me to a room with an Oculus Rift and Sansar fired up on a computer. The first virtual space we entered was a breezy outdoor basketball court in a sunny beach location. The visuals were crisp, and off to the side, music was coming from a boom box. There were also some virtual basketballs lying on the court, and I was pleased to find that I could bounce and throw them using my touch controllers.

When Altberg headed down the hall to settle into his own Rift, a pudgy devil mascot with his voice coming from it suddenly spawned next to me. The first thing I noticed was that his character’s lips moved in the way I’d expect them to if he were speaking in real life. Sansar uses a facial animation technology that syncs an avatar’s lip movement with the user’s actual speech in real time, something I had not seen in other social VR platforms and which added realism.

We spent a few minutes tossing the basketballs and wandering the space. Within moments, I felt immersed in the experience, like I was actually hanging out with someone at a basketball court.

“This whole thing was created by one of my team—a guy who’s not a 3D modeler or programmer,” Altberg tells me. I later learned that Sansar’s VP of Product, Bjorn Laurin, created the entire space with his six-year-old son in a single afternoon simply by dropping assets from the Sansar store into the scene.

And this—at the core—is the focus of Sansar: making it as easy as possible for anyone who wants to design, build, publish, share, and experience a virtual world.

“Sansar democratizes building social VR experiences, something that involves complex engineering, so it’s no longer limited to just professional developers. Much like creating a website was something that only engineering organizations could do many years ago—and now there are solutions like WordPress—that’s an analogy we sometimes use for Sansar. You can think of it like a ‘Wordpress for social VR’,” Altberg says.

And much like Second Life, where everything is made by the users themselves, Sansar will be a collection of worlds built by the people who use it. Developers will be able to upload and sell virtual items—things like palm trees, furniture, performance stages, whatever—that others can purchase and use in their space.

Be Part of the Future

Sign up to receive top stories about groundbreaking technologies and visionary thinkers from SingularityHub.

Image Credit: Sansar/YouTube

For Linden Lab, one major strategic update from Second Life is the business model they’ve selected.

“Second Life’s business model was primarily based on renting virtual land for people to build on, which for us, equates to renting them server space,” Altberg says.

Second Life users pay roughly $300 per month for a plot of land, and that’s a high cost for someone just trying to tinker about. Sansar, by contrast, plans to drop the hosting fees and make up for those costs by taking a cut of the transactions that occur between users.

Another change means that Sansar worlds will be discoverable with a regular internet search. “Second Life was and is a closed world,” Altberg said. “In order to discover an experience there, you needed to be a user logged into Second Life. With Sansar, our publishers will able to link to their experiences from other sites.”

And perhaps the biggest change coming to Sansar is the sheer scale available to developers.

A full region of land in Second Life is 256 meters by 256 meters, but in Sansar, every scene can be as large as four kilometers by four kilometers. “You can also interconnect those spaces together to develop scenes on a massive scale,” Altberg adds.

Society May Finally Be Ready for Virtual Living

So Sansar is preparing for release into a world in which technology has developed exponentially for fourteen years—a world where consumer VR headsets have finally arrived. And perhaps the primary reason Linden Lab might succeed in building a mainstream virtual world is that society in the real world may finally be ready. Cultural norms may have caught up to the idea of virtual life.

“When Second Life began, so many of the conceptual elements of virtual worlds were so foreign to people,” Gray says.

Fourteen years ago, the idea that people might digitally interact with other people they didn’t know in real life was entirely unfamiliar. Yet in the past decade, social media platforms like Facebook and Twitter have reshaped human behavior.

Behaviors that were once exotic have become entirely ordinary. Society has become native to virtual living.

“These are massive cultural changes that are still very recent,” Gray says. “User-created content was still in its infancy back when we started. It’s true that YouTube was getting off the ground around the same time we were, but it was certainly not at the volume that you have today. When Second Life started, Apple hadn’t even launched their app store, and so the idea that people might pay real money for digital items that they would never physically hold in their hands was still a crazy idea to many people.”

Now, behaviors that were once exotic have become entirely ordinary. Things like online shopping, paying for “apps,” and hanging out with friends online are unremarkable features of the modern age. Society has become native to virtual living.

Though Second Life achieved considerable success, it was born in an era that was never quite ready for it. Now, Linden Lab is preparing to release Sansar into a world that’s been forever reshaped by the effects of the social media age.

It could be that society is finally ready for life inside the virtual worlds of our own creation.

Sansar will be available to the public in beta this summer.

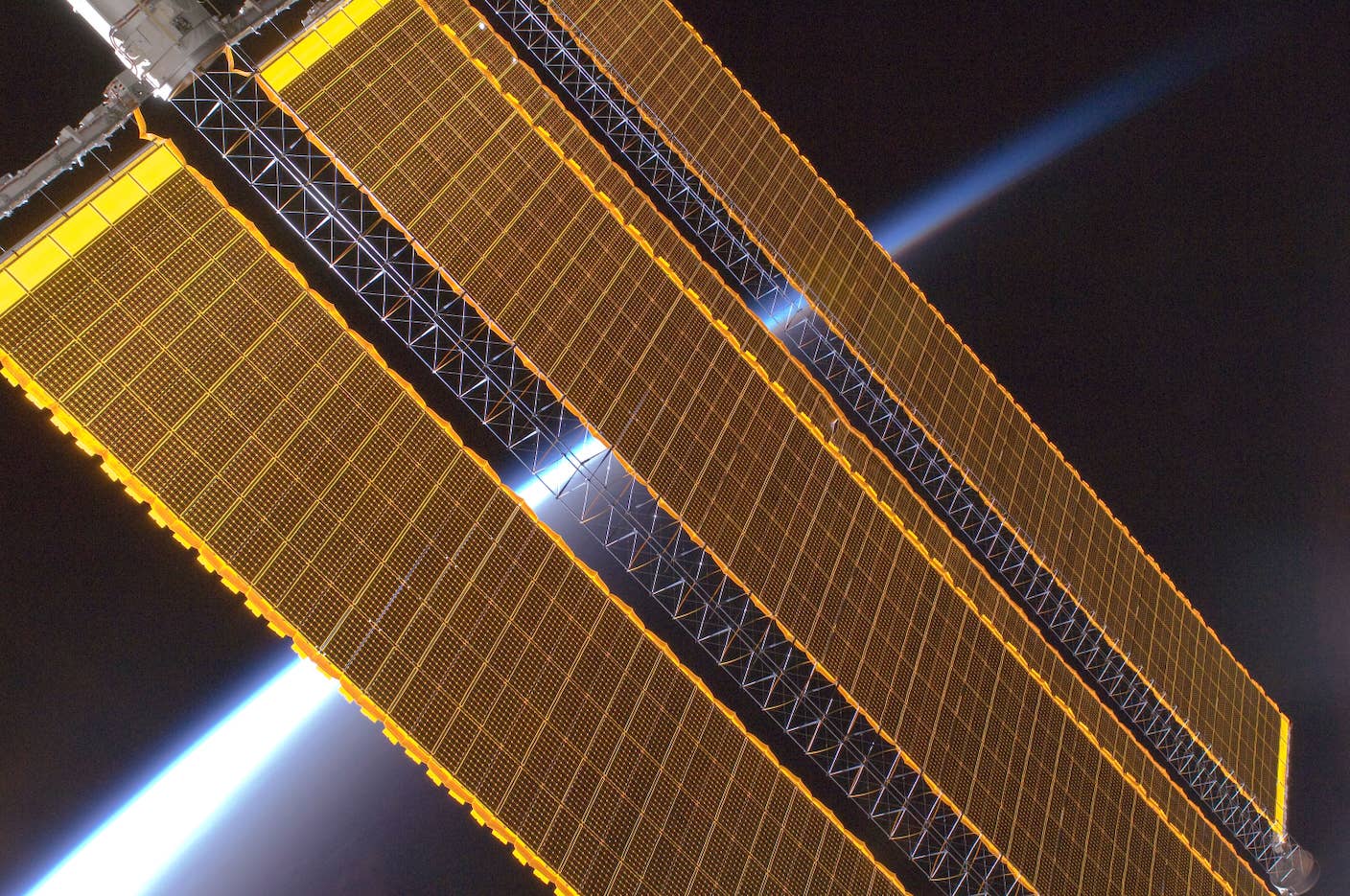

Image Credit: Linden Lab / Sansar

Aaron Frank is a researcher, writer, and consultant who has spent over a decade in Silicon Valley, where he most recently served as principal faculty at Singularity University. Over the past ten years he has built, deployed, researched, and written about technologies relating to augmented and virtual reality and virtual environments. As a writer, his articles have appeared in Vice, Wired UK, Forbes, and VentureBeat. He routinely advises companies, startups, and government organizations with clients including Ernst & Young, Sony, Honeywell, and many others. He is based in San Francisco, California.

Related Articles

Data Centers in Space: Will 2027 Really Be the Year AI Goes to Orbit?

New Gene Drive Stops the Spread of Malaria—Without Killing Any Mosquitoes

These Robots Are the Size of Single Cells and Cost Just a Penny Apiece

What we’re reading