NASA Twins Study Provides New Insight Into How Space Travel Affects Human Health

Share

Thanks to 18 years of humans continuously working on the International Space Station (ISS), we already have a basic idea of what happens to our Earth-grown bodies in zero gravity. Our hearts morph in shape, lowering the amount of oxygen the blood can absorb and carry. Our bones and muscles wither without gravitational challenge. Fluids rush towards our heads, increasing pressure in the eyes.

Many of these symptoms seem to worsen the longer humans remain in space. Yet with space missions often only lasting six months, how our bodies and minds adapt to long-term space flight—that is, if we can at all—remains a complete mystery.

Until now. This week, an ambitious collaboration organized by NASA of over 80 scientists across ten teams published the most comprehensive study yet of what happens to humans in space—and upon return to our pale blue dot.

The news is good. Overall, the data “demonstrated on the molecular level the resilience and robustness of how one human body adapted to the spaceflight environment,” said Dr. Jenn Fogarty, chief scientist of the NASA Human Research Program. “This study was a stepping stone to future biological space research focusing on molecular changes and how they may predict health and performance of astronauts.”

Landmark Effort

The actual results aren’t even the most impressive parts of the study. Rather, the technical tour-de-force stands out in its sheer scope and study subjects.

For 25 months, the teams examined astronauts before, during, and after a year of spaceflight. By analyzing multiple time points, they were able to construct stop-motion “movies” that track changes in their biology over time in exquisite detail. The results span nearly the entire spectrum of biomedicine: at the micro-level, from gene expression, DNA damage, and cellular metabolism to changes in the microbiome and immune system; at the macro-level, shifts in cognition, body weight, eyesight, and cardiovascular functions.

It marks the first time NASA examined multiple layers of biological data, or “multi-omics” for space travel.

But perhaps more unique were the study subjects: astronauts Scott and Mark Kelly, a pair of identical twins. Although Mark had previously spent short bouts in space, he remained on Earth for the duration of this study—aptly named the NASA Twin Study—while Scott spent 340 days on the ISS. Because the astronauts share the same basic genetic blueprint, “nature,” scientists had an exceptional opportunity to tease out the effect of “nurture”—space travel.

The caveat is that the results and conclusions may not entirely hold for others. “We really can’t say if any of the results are due to space travel or coincidence,” the team acknowledged. However, their data does indicate areas to focus on in future studies involving other astronauts, which could eventually allow them to understand and counteract the negative health effects of space, they said.

With commercial spaceflight ramping up, a return to the moon in the works, and a three-year venture to Mars within sight, we’re eagerly scattering into the final frontier. Guided by the Twin Study, these future projects will offer new opportunities to further “contextualize” our physiology in long-term spaceflight, the authors said.

Limited Changes in Store

When it comes to specific bodily changes the conclusions get murkier.

First, the genes. Radiation is a known trigger for DNA damage, and the teams found extensive changes in Scott’s DNA expression—how his genes make proteins—compared to his brother.

Some of the changes were expected: those involved in bone repair and DNA repair, for example, which kept up even after Scott returned to Earth, suggesting his genome was relatively unstable. The teams also found changes in his mitochondrial genes, which could control how cells generate energy, as well as several genes related to his immune system . Whether those genetic changes actually affected his immune system is unclear; a flu vaccine given to Scott in space worked as intended.

"Gene expression changed dramatically," said Mason, whose team worked on genomics. "In the last six months of the mission, there were six times more changes in gene expression than in the first half of the mission."

However, over 91 percent of expression changes reverted back to baseline for Scott within six months after he returned home. “Overall, these data show plasticity and resilience for many core genetic…and biological functions,” the team concluded.

Dr. Andrew Feinberg and Dr. Lindsay Rizzardi explains why studying twin astronauts helps tease out health factors related to spaceflight. Credit: Johns Hopkins Medicine

More startling were Scott’s telomeres, the “end caps” that protect chromosomes when they replicate. The guardians of the genome, telomeres are known to shorten with age, which could explain why our genome becomes more unstable as we age. Shockingly, Scott’s telomeres became longer in space—generally considered a protective response.

Be Part of the Future

Sign up to receive top stories about groundbreaking technologies and visionary thinkers from SingularityHub.

"We were surprised, that was the first reaction," said Dr. Susan Bailey at Colorado State University, who led the study.

Susan Bailey explains her findings about telomere changes in space and upon returning to Earth. Credit: Colorado State University.

However, within months of returning, the team found more “frayed” chromosome ends, suggesting that some of Scott’s telomeres had disintegrated to the point of complete loss. The health effects aren’t immediately clear; short telomeres correlate with age-related diseases such as heart disease and cancer, for example, but whether Scott is now at higher risk for these health problems remains anyone’s guess. Nevertheless, telomere shortening is a clear field for scientists to keep exploring.

Second, the body. Similar to previous cases, Scott had problems with his eyes due to fluid buildup, and some of the issues remained even coming home, whereas his Earth-bound brother experienced no eye problems during the study. In flight, Scott’s cardiovascular system also suffered, resulting in “puffy face” syndrome, and his immune system ramped up, suggesting that his body was under a state of stress. His kidney function also changed in a way to could lead to dehydration and kidney stones, although he didn’t have any issues.

Finally, when subjected to a battery of cognitive tests, Scott performed worse in nearly all of them except for spatial orientation after his space flight, and both his speed and accuracy of reasoning seemed to suffer for at least half a year upon returning home. Scientists aren’t quite sure if space is to blame: the trauma of re-entering Earth and the demand for astronauts to participate in research studies and media events could have taxed his mental reservoir during the exam, resulting in poor performance.

Above and Beyond

The Twin Study, although remarkable, is only the beginning.

To gather data in space, the teams developed a bank of new tools, such as a portable DNA sequencing technique that works aboard the ISS. Although not used in this study, the sequencer could eventually allow astronauts to “read” their own DNA in microgravity during longer spaceflights without relying on home command.

And looking ahead, a year in space isn’t that long. A round trip to Mars is projected to last three years, during which astronauts would be exposed to even more radiation as they travel beyond the protection of Earth’s magnetic field. We’ll need more studies examining the health impact of even longer spaceflight in the future.

But this effort is a foundation-building start.

“Undoubtedly, the study…represents more than one small step for mankind in this endeavor,” concluded Löbrich.

Image Credit: Andrey Armyagov / Shutterstock.com

Dr. Shelly Xuelai Fan is a neuroscientist-turned-science-writer. She's fascinated with research about the brain, AI, longevity, biotech, and especially their intersection. As a digital nomad, she enjoys exploring new cultures, local foods, and the great outdoors.

Related Articles

Elon Musk Says SpaceX Is Pivoting From Mars to the Moon

What If We’re All Martians? The Intriguing Idea That Life on Earth Began on the Red Planet

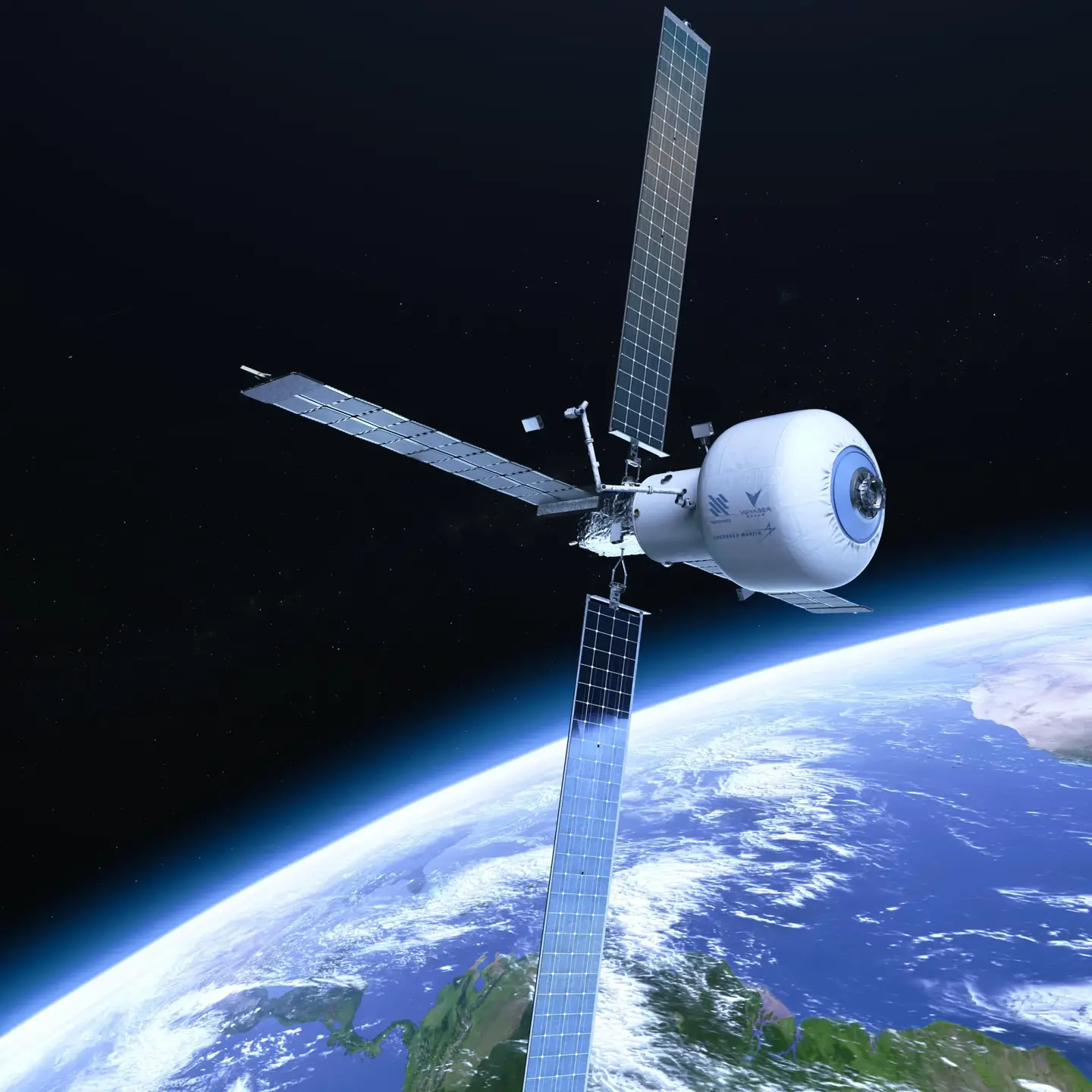

The Era of Private Space Stations Launches in 2026

What we’re reading