In late December 2019 Dr. Li Wenliang, an ophthalmologist at Wuhan Central Hospital, sent a WeChat message to his medical school alumni group telling them that seven people with severe respiratory and flu-like symptoms had recently been admitted to the hospital. One thing they had in common, besides their symptoms, was that they’d all visited a local wet market at some point in the previous week.

The illness bore an uncanny resemblance to SARS, but with a novel aspect as well; could it be an outbreak of a new disease? If so, what should be done?

But before any of the doctors could take action or alert local media outlets, the chat thread was shut down by the Wuhan police and Li was accused of spreading rumors. Mind you, the chat wasn’t in a public forum; it was a closed group exchange. But the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) is able to monitor, intercept, and censor any and all activity on WeChat; for the Chinese people, there’s no such thing as a private conversation.

The police gave Li an affidavit stating he’d spread false information and disturbed public order. He was instructed to sign this document retracting his warning about the virus and to stop telling people it existed, otherwise he’d be put in jail.

So he did. A little over a month later, on February 7, Li died of the novel coronavirus in the same hospital where he’d worked—he’d been infected with the virus while trying to treat sick patients, who’d continued pouring into the hospital throughout the month of January.

By this time the CCP had leapt into action, unable to deny the existence of the virus as hundreds then thousands of people started getting sick. Travel restrictions and quarantines went into effect—but it was already far too late. As of this writing, the virus has spread to 168 countries and killed almost 21,000 people. Schools and businesses are closed. We’re in lockdown mode in our homes. And the economy is taking a massive hit that could lead to a depression.

How different might our current situation be if the CCP had heeded Li’s warning instead of silencing it—or if the virus had first been discovered in a country with a free press?

“People are arguing that China has done a good job of handling the virus. I disagree,” said Alex Gladstein, chief strategy officer at the Human Rights Foundation. “The reason we have this global pandemic right now is because of Chinese censorship and the government’s totalitarian nature.”

Last week at Singularity University’s virtual summit on COVID-19, Gladstein pointed out what we can learn from various governments’ responses to this pandemic—and urged us to keep a close eye on our freedoms as this crisis continues to unfold.

Open, Competent, or Neither?

The rate at which this disease has spread in different countries has varied wildly, as have the numbers of deaths vs. recoveries. Western Europe houses some of the wealthier and more powerful countries on Earth, but now isn’t a great time to be living there (and we’re not doing so hot in the US, either). And though Singapore is known for its rigidity, it was a good place to be when the virus hit.

“Given a half-century of research, the correlation is strong: democracies handle public health disasters much better than dictatorships,” Gladstein said, citing a February 18th article in The Economist that examines deaths from epidemics compared to GDP per person in democracies and non-democracies.

Taiwan has also fared well, as has South Korea, though their systems of government function quite differently than Singapore’s. So what factors may have contributed to how fast the virus has spread and how hard the economy’s been hit in these nations?

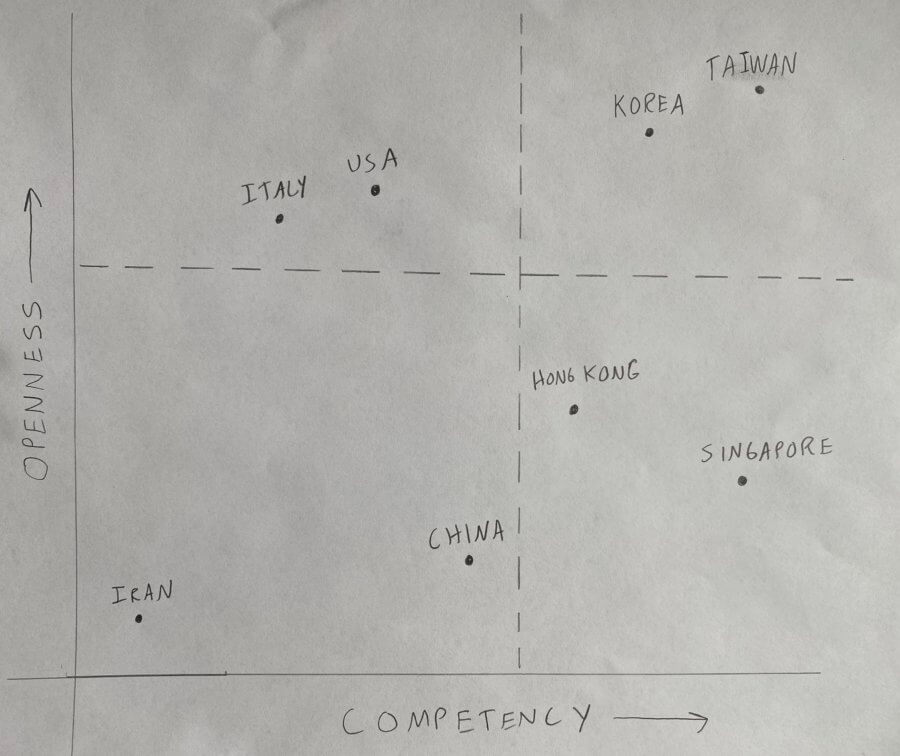

There are two axes that are relevant, Gladstein said. One is the openness of a society and the other is its competency. An open but less competent government is likely to perform poorly in a public health crisis (or any crisis), as is a competent but closed government.

“Long-term, some of the best-performing societies are open, competent democracies like Korea and Taiwan,” Gladstein said. Taiwan is a somewhat striking example given its proximity to China and the amount of travel between the two.

Success Here, Failure There

With a population of 23 million people and the first case confirmed on January 21, as of this writing Taiwan has had 235 cases and 2 deaths. They immediately started screening people coming from China and halted almost all incoming travel from China within weeks of the outbreak, creating a risk-level alert system by integrating data from the national health insurance database with the immigration and customs databases (this did involve a degree of privacy infringement that we probably wouldn’t be comfortable with in the US; more on that later). High-risk people were quarantined at home, and the government quickly requisitioned the manufacture of millions of masks. “There was less panic and more belief in the government, and this paints a picture of what we should all aspire to,” Gladstein said.

Iran is on the opposite end of the spectrum in both competency and openness; they’ve recorded over 27,000 cases and over 2,000 deaths. “Thousands have died in Iran, but we’ll never know the truth because there’s no free press there,” said Gladstein.

Then there’s China. In addition to lockdowns enforced by “neighborhood leaders” and police, the government upped its already-heavy citizen surveillance, tracking people’s locations with apps like AliPay and WeChat. A color-coding system indicating people’s health status and risk level was implemented, and their movement restricted accordingly.

“They’ve now used the full power of the state to curtail the virus, and from what we know, they’ve been relatively effective,” Gladstein said. But, he added, this comes with two caveats: one, the measures China has taken would be “unthinkable” in a democracy; and two, we can’t take their data at face value due to the country’s lack of a free press or independent watchdogs (in fact, the New York Times, Wall Street Journal, and Washington Post were expelled from China on March 17; this may have been a sort of retaliation for the US State Department’s recent move to cap the number of Chinese journalists allowed to work in the US for a handful of Chinese state media outlets).

Surveillance = Success?

South Korea and Singapore, the world’s other two containment success stories, both used some form of surveillance to fight the virus. In Korea, the 2015 MERS outbreak resulted in a law that lets the government use smartphone and credit card data to see where people have been then share that information (stripped of identifying details) on apps so that people they may have infected know to go get tested.

In Singapore, besides launching a contact tracing app called TraceTogether, the government sent text messages to people who’d been ordered to stay at home and required them to respond with their live GPS location. As of this writing, Singapore had reported 631 cases and 2 deaths.

Does the success of these countries and their use of surveillance mean we need to give up some of our privacy to fight this disease? Would Americans and Europeans be willing to do so if it meant this terrible ordeal would be over sooner? And how do we know where to draw the line?

Would you be willing to sacrifice some of your privacy and personal liberties, such as having your whereabouts more closely tracked (via GPS on your phone and your credit card transactions) and input into a public database, if it meant coronavirus would be stopped sooner?

— Singularity University (@singularityu) March 26, 2020

Temporary May Be Tricky

To Gladstein, the answer is simple. “We don’t need a police state to fight public health disasters,” he said. “We should be very wary about governments telling us they need to take our liberties away to keep us safe, and that they’ll only take those liberties away for a limited amount of time.”

A lot of personal data is already being collected about each of us, every day: which ads we click on, how long we spend on different websites, which terms we search for, and even where we go and how long we’re there for. Would it be so terrible to apply all that data to stemming the spread of a disease that’s caused our economy to grind to a halt?

One significant issue with security measures adopted during trying times is that those measures are often not scaled back when society returns to normal. “During the 2008 Olympics in Beijing, the government said the new security measures were temporary, but they turned out to be permanent,” Gladstein said.

Similarly, writes Yuval Noah Harari in a Financial Times piece (which you should read immediately in its entirety if you haven’t already), “Temporary measures have a nasty habit of outlasting emergencies, especially as there is always a new emergency lurking on the horizon.” Many of the emergency measures enacted during Israel’s War of Independence in 1948, he adds, were never lifted.

Testing, Transparency, Trust

This is key: though surveillance was a critical part of Taiwan, Korea, and Singapore’s success, widespread testing, consistent messaging, transparency, and trust were all equally critical. In an excellent piece in Wired, Andrew Leonard writes, “In the United States, the Trump administration ordered federal health authorities to treat high-level discussions on the coronavirus as classified material. In Taiwan, the government has gone to great lengths to keep citizens well informed on every aspect of the outbreak.”

In South Korea, President Moon Jae-in minimized his own communications with the public, ceding the sharing of information to those who actually knew it: health officials updated the public on the state of the pandemic twice a day. Singapore’s government provided consistent, clear updates on the number and source of cases in the country.

Gladstein re-emphasized that democracies are better suited than dictatorships at handling public health crises because people need to be able to innovate and collaborate without fear.

But despite a high level of openness that includes democratic elections, some of the heaviest emphasis on individual rights and freedoms in the world, and a free press, the US response to coronavirus has been dismal. As of this writing, more than 25 US states have ordered residents to be on lockdown. But testing, trust, and transparency are all sorely lacking. As more people start to fall seriously ill in the coming days and weeks, what will the US do to stem Covid-19’s spread?

“Secrecy, lies, and censorship only help the virus,” Gladstein said. “We want open societies.” This open society is about to be put to the test—big-time.

For more from Gladstein on this topic, read his recent opinion piece in Wired.

Image Credit: Brian McGowan on Unsplash