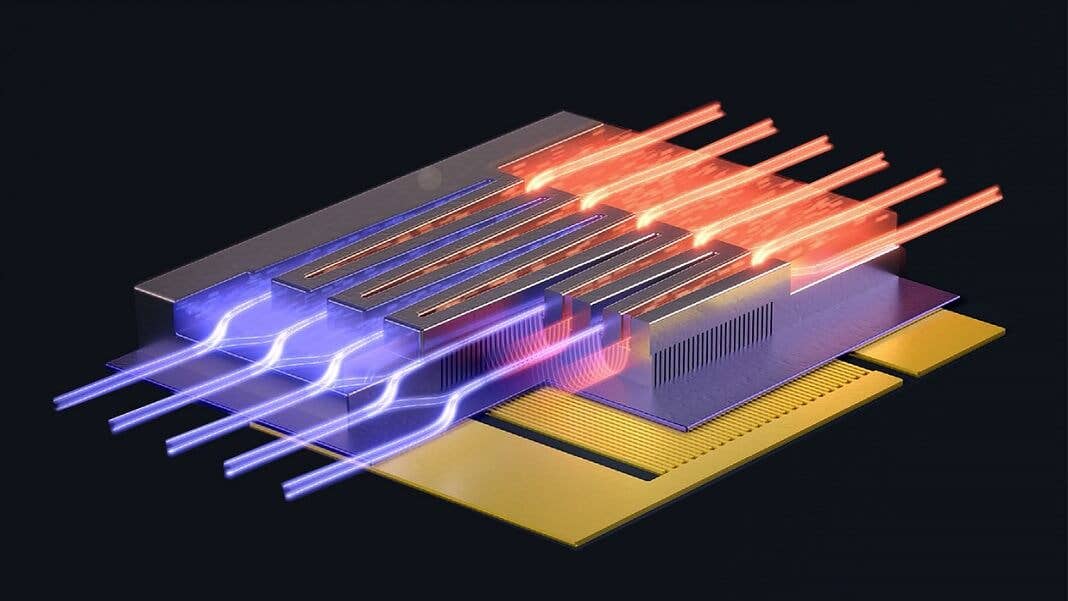

This Microchip Has Its Own Built-In Cooling System

Share

As we pack electronics into ever smaller packages, dealing with the heat they produce is becoming a growing challenge. Now researchers have developed a liquid cooling system integrated directly within a microchip that dramatically outperforms previous approaches.

For decades the way we’ve boosted the power of computers and other electronics has been to squeeze more and more transistors on each chip. But each of these components gives off heat as they carry out their tasks, which quickly adds up as they are packed ever closer together.

If chips get too hot they malfunction, so this is already a major obstacle for further miniaturizing electronics, and it’s also an unsustainable resource drain on big technology companies with lots of hardware. Data centers in the US consume 24 terawatt-hours of electricity and 100 billion liters of water a year, which is equivalent to the residential requirements of the city of Philadelphia.

A new approach that builds microfluidic cooling channels into chips could provide dramatically better cooling using far less water. The design, reported in a paper in Nature, is capable of 50 times the performance of state-of-the-art alternative cooling systems, according to the authors.

"This cooling technology will enable us to make electronic devices even more compact and could considerably reduce energy consumption around the world," study leader Elison Matioli from École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne in Switzerland said in a press release.

Most chips today are cooled by using thermal materials to transfer heat from components to a large metal heat sink that dissipates the energy to the air, possible with the help of a fan. This is highly inefficient, and therefore overheating is still a major problem for most electronics.

Using liquid to cool chips is much more efficient, but most attempts so far have involved retrofitting some kind of radiator-like device onto the chip as an afterthought. The key to the new approach is that the cooling system has been designed into the chip right from the start to maximize heat transfer.

"We placed microfluidic channels very close to the transistor's hot spots, with a straightforward and integrated fabrication process, so that we could extract the heat in exactly the right place and prevent it from spreading throughout the device," said Matioli.

Be Part of the Future

Sign up to receive top stories about groundbreaking technologies and visionary thinkers from SingularityHub.

Their approach relies on a novel process for etching channels directly into the chip substrate. To demonstrate its effectiveness they built a circuit that can convert AC current to DC current and showed that it could easily cope with heat fluxes of 1,700 watts per square centimeter.

Normally this kind of circuit would require a fist-sized heat sink, but the team was able to squeeze it onto a USB stick-sized piece of circuit board and cool it with a water flow of less than a milliliter per second.

So far, the researchers have only implemented their approach on power electronics devices, which are responsible for controlling and converting electricity and are quite different from the data-processing circuits found in computers. And there are reasons to believe it would be quite a challenge to replicate their approach in other kinds of chips.

For a start, power electronics are generally built from gallium nitride semiconductors rather than silicon. But more importantly, these chips are far simpler than general-purpose processors. Writing in Ars Technica, John Timmer points out that aligning the coolant channels with all the components in a much more complex chip—whose activity could fluctuate based on the task—would be very tricky.

Nonetheless, these power circuits are present in all kinds of electronics, from data centers to electric vehicles, so boosting their efficiency could still slash a significant chunk off our cooling bills. It should also help cut the size and weight of these crucial components, which could help us pack far more electronics into constrained platforms like drones or wearables.

Image Credit: Vytautus Navikas/EPFL

Related Articles

Scientists Send Secure Quantum Keys Over 62 Miles of Fiber—Without Trusted Devices

This Light-Powered AI Chip Is 100x Faster Than a Top Nvidia GPU

How Scientists Are Growing Computers From Human Brain Cells—and Why They Want to Keep Doing It

What we’re reading