A Self-Driving Truck Got a Shipment Cross-Country 10 Hours Faster Than a Human Driver

Share

Self-driving cars are taking longer to come to market than many expected. In fact, it’s looking like they may be outpaced by pilotless planes and driverless trucks, with self-driving technology already coming in handy on long-haul trucking routes, as a recent cross-country trip showed.

Last month TuSimple, a transportation company focused on self-driving technology for heavy-duty trucks, shipped a load of watermelons from Arizona to Oklahoma using an autonomous system for over 80 percent of the journey. The starting point was Nogales, at Arizona’s southern end right on the border with Mexico. A human driver took the wheel for the first 60 miles or so, from Nogales to Tucson—but from there the truck went on auto-pilot, and not just for a little while. It drove itself all the way to Dallas, 950 miles to the east (there was a human safety driver on board the whole time, but not controlling the truck).

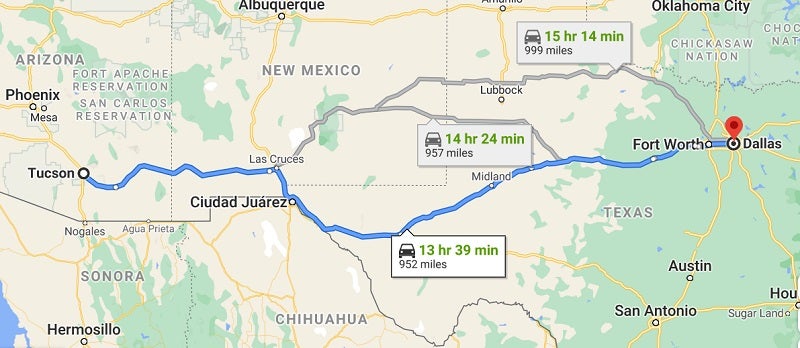

Tucson to Dallas via I-10 and I-20

If you look at the most direct route, it’s pretty straightforward: there’s one fork where I-10 splits off and merges with I-20, but other than that, it’s straight on through ‘til morning. Literally, in this case; the truck drove the route in 14 hours and 6 minutes, as compared to the given estimate of the average time it takes a human to drive the same route—24 hours and 6 minutes.

That’s a 42 percent savings on time. But the 24-hour estimate is pretty conservative, if you ask me, depending how fast you’re going and how much coffee you’re drinking. Not too long ago I drove 960 miles—almost the exact same distance—in 14 hours and 20 minutes. Did it take my body days to stop aching afterwards? Yes. Did I get a $120 speeding ticket in eastern Iowa? Yes. Was it worth it? Sort of/not really. But you get my point.

Trucks are slower than cars, admittedly. And perhaps most importantly, there's actually a law that limits truck drivers from being on the road for longer than 14 consecutive hours; within that span of time they can be driving for 11 hours, and they have to have been off-duty for at least 10 hours prior. It's pretty self-explanatory, but the rule exists to keep overtired drivers off the road and prevent accidents. So even if a driver is willing and able to drive for, say, 16 hours straight (with bathroom and fuel breaks, and an abundant supply of easy-to-eat-with-one-hand meals and snacks), they're technically not allowed to do so.

From Dallas, the human driver took over again and drove the final 200 miles to a distribution center in Oklahoma City. There the watermelons were inspected—nothing to see here, they were in better shape than they would’ve been with a human driving the whole time—then distributed to stores all over the state.

The reason the watermelons were in better shape was because they were a day fresher. This is one angle TuSimple is hoping will boost its business. “We believe the food industry is one of many that will greatly benefit from the use of TuSimple's autonomous trucking technology," said Jim Mullen, the company’s chief administrative officer. “Given the fact that autonomous trucks can operate nearly continuously without taking a break means fresh produce can be moved from origin to destination faster, resulting in fresher food and less waste.”

The watermelon delivery trial was done as part of a partnership with Giumarra, a network of produce growers and distributors, and Associated Wholesale Grocers, the biggest cooperative food wholesaler for independently-owned supermarkets in the US.

Last summer, TuSimple announced plans to build a nationwide network of self-driving trucks, complete with digitally-mapped routes, terminals, and a central operations system. They already operate seven routes between Phoenix, Tucson, El Paso, and Dallas, and are in the process of adding routes to Houston and San Antonio.

Be Part of the Future

Sign up to receive top stories about groundbreaking technologies and visionary thinkers from SingularityHub.

They haven’t had to jump too many legal hurdles, at least not at a federal level; federal regulations don’t cover automated driving systems at present, with responsibility left to individual states. Texas is an optimal state in which to carry out tests like this: tons of space, good weather, huge highways running both north-south and east-west, and a 2017 bill allowing vehicles to operate without a driver.

A hearing in mid-May, however, (titled, dramatically yet vaguely, “Promises and Perils: The Potential of Automobile Technologies”) had a committee discuss rules for driverless vehicles and incentives for growing the industry.

If regulation is one looming question around automating freight, another is technological unemployment: what about all the human drivers who’ll be left without jobs when computers take over hauling produce from state to state?

What may actually happen is that autonomous driving tech helps fill a shortage of labor in long-haul trucking, which is seeing increasingly high turnover, particularly with entry-level drivers. An episode of NPR’s Planet Money from August 2020 discussed how the job has gotten harder on workers. And humans will still be a big part of the equation for many years to come, acting as safety and last-mile drivers—and their jobs will be a lot easier than they are now.

TuSimple is well-positioned to start putting more trucks on the road, safety drivers and all: the company’s initial public offering in April raised over $1 billion, and was valued at almost $8.5 billion. They’ve got their work cut out for them; the company is aiming for its trucks to operate without safety drivers on board by the end of 2024.

Image Credit: TuSimple

Vanessa has been writing about science and technology for eight years and was senior editor at SingularityHub. She's interested in biotechnology and genetic engineering, the nitty-gritty of the renewable energy transition, the roles technology and science play in geopolitics and international development, and countless other topics.

Related Articles

This Week’s Awesome Tech Stories From Around the Web (Through February 21)

What the Rise of AI Scientists May Mean for Human Research

This ‘Machine Eye’ Could Give Robots Superhuman Reflexes

What we’re reading