Nissan and NASA Are Teaming Up to Make a Metal-Free Solid-State Battery

Share

The slow but steady transition to renewable energy was already underway when Russia invaded Ukraine in February, and since then the global energy market has been turned on its head. We’re likely to witness more upheaval as the geopolitical energy landscape sees power shift away from countries rich in oil and gas towards those rich in materials critical for making batteries, electric cars, solar panels, wind turbines, and the like. In fact, the push for clean energy is already contributing to a trend toward protectionism, and this trend is only going to continue as the stakes get higher.

Rather than waiting to be squeezed by tariffs or supply shortages, some organizations are pre-emptively making moves to be as self-sufficient as possible in what will likely be a volatile market. Two such organizations are Nissan and NASA. The carmaker and the space agency may not appear to have a ton in common, but one interest they do share is cheap, scalable, energy-dense batteries. Last week they announced a partnership aimed at developing solid-state batteries.

The lithium-ion batteries used today in everything from smartphones to electric vehicles rely on a liquid electrolyte to move lithium ions between a graphite anode (the negative electrode) and a cathode (the positive electrode), which can be made from various materials.

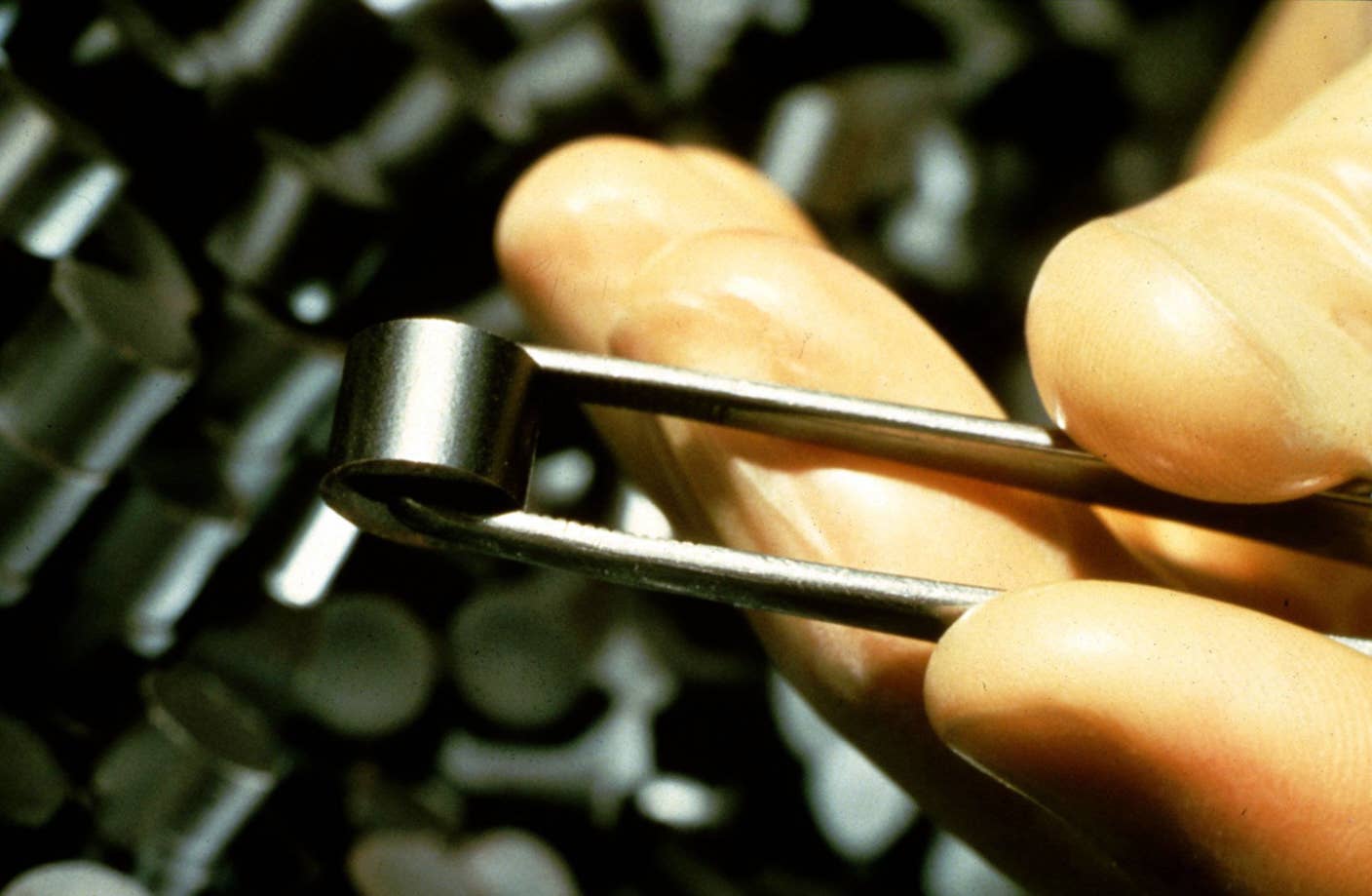

Solid-state batteries swap the liquid electrolyte out for—you guessed it—a solid one, increasing the energy density two-fold or more. Efforts to develop these batteries have been plagued by complications, including finding an effective replacement for the separator (the component that keeps the anode and cathode apart while allowing lithium ions to pass through), and solving problems like oxidative degradation and dendrite formation (needle-like projections from the lithium anode that can pierce the separator).

The Nissan-NASA initiative is similar to one announced over two years ago by IBM and Mercedes-Benz; the computing powerhouse and the carmaker planned to use both classical and quantum computing to design solid-state batteries, including simulating the properties of molecules for solid-state lithium-sulfur batteries. In late 2019 they unveiled a “heavy-metal-free” battery whose materials could supposedly be extracted from sea water.

Crucially, the Nissan-NASA partnership is also focusing on batteries that don’t rely on rare metals, like cobalt (of which more than half the global supply is in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, as highlighted in an episode of the New York Times Daily podcast last month), nickel, or manganese.

Be Part of the Future

Sign up to receive top stories about groundbreaking technologies and visionary thinkers from SingularityHub.

But getting rid of those metals means finding materials with comparable properties to replace them, which will be no simple task. Here’s where NASA’s computing chops will lend the partnership a much-needed hand. They plan to create an original material informatics platform—that is, a massive database that runs simulations of how various materials interact with one another. When the platform narrows countless options and combinations down to a few prime candidates, researchers can then start testing them.

Nissan has targeted 2028 as the year to roll out its proprietary solid-state batteries. How realistic that timing turns out to be remains to be seen (Toyota is even more ambitious, aiming to have its own vehicles with solid-state batteries on the market by 2025), but Nissan is putting its money where its mouth is with plans to open a pilot plant in Japan in 2024. How this plays out will be revelatory, as scaling up manufacturing of solid-state batteries has produced unexpected complications in the past. Encouragingly, startup Solid Power has also targeted 2028 for commercializing its solid-state batteries.

We don’t yet know how long it will take, but one thing is looking pretty certain: as the scramble to secure reliable energy supplies continues over the following months and years, we’re likely to see many more efforts to bring batteries and related technology in-house.

Image Credit: bixusas / 43 images

Vanessa has been writing about science and technology for eight years and was senior editor at SingularityHub. She's interested in biotechnology and genetic engineering, the nitty-gritty of the renewable energy transition, the roles technology and science play in geopolitics and international development, and countless other topics.

Related Articles

Meta Will Buy Startup’s Nuclear Fuel in Unusual Deal to Power AI Data Centers

Your ChatGPT Habit Could Depend on Nuclear Power

Hugging Face Says AI Models With Reasoning Use 30x More Energy on Average

What we’re reading