How Plate Tectonics, Mountains, and Deep-Sea Sediments Have Maintained Earth’s ‘Goldilocks’ Climate

Share

For hundreds of millions of years, Earth’s climate has warmed and cooled with natural fluctuations in the level of carbon dioxide (CO₂) in the atmosphere. Over the past century, humans have pushed CO₂ levels to their highest in two million years—overtaking natural emissions—mostly by burning fossil fuels, causing ongoing global warming that may make parts of the globe uninhabitable.

What can be done? As Earth scientists, we look to how natural processes have recycled carbon from atmosphere to Earth and back in the past to find possible answers to this question.

Our new research published in Nature shows how tectonic plates, volcanoes, eroding mountains, and seabed sediment have controlled Earth’s climate in the geological past. Harnessing these processes may play a part in maintaining the “Goldilocks” climate our planet has enjoyed.

From Hothouse to Ice Age

Hothouse and icehouse climates have existed in the geological past. The Cretaceous hothouse (which lasted from roughly 145 million to 66 million years ago) had atmospheric CO₂ levels above 1,000 parts per million, compared with around 420 today, and temperatures up to 10℃ higher than today.

But Earth’s climate began to cool around 50 million years ago during the Cenozoic Era, culminating in an icehouse climate in which temperatures dropped to roughly 7℃ cooler than today.

What kickstarted this dramatic change in global climate?

The Earth evolved from a hothouse climate in the Cretaceous period (left) to an icehouse climate in the following Cenozoic era (right), leading to inland ice sheets. Image Credit: F. Guillén and M. Antón / Wikimedia Commons

Our suspicion was that Earth’s tectonic plates were the culprit. To better understand how tectonic plates store, move, and emit carbon, we built a computer model of the tectonic “carbon conveyor belt.”

The Carbon Conveyor Belt

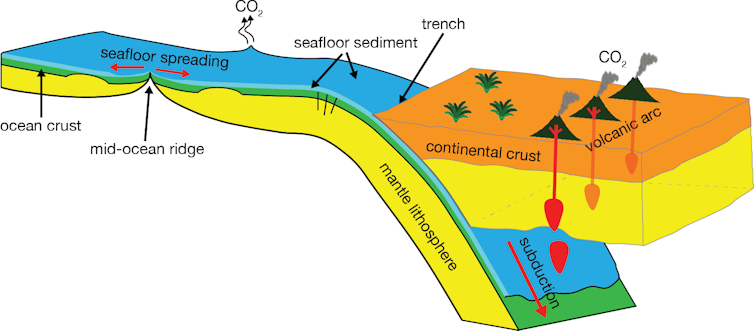

Tectonic processes release carbon into the atmosphere at mid-ocean ridges—where two plates are moving away from each other—allowing magma to rise to the surface and create new ocean crust.

At the same time, at ocean trenches—where two plates converge—plates are pulled down and recycled back into the deep Earth. On their way down they carry carbon back into the Earth’s interior, but also release some CO₂ via volcanic activity.

The Earth’s tectonic carbon conveyor belt shifts massive amounts of carbon between the deep Earth and the surface, from mid-ocean ridges to subduction zones, where oceanic plates carrying deep-sea sediments are recycled back into the Earth’s interior. The processes involved play a pivotal role in Earth’s climate and habitability. Image Credit: Author provided

Our model shows that the Cretaceous hothouse climate was caused by very fast-moving tectonic plates, which dramatically increased CO₂ emissions from mid-ocean ridges.

In the transition to the Cenozoic icehouse climate, tectonic plate movement slowed down and volcanic CO₂ emissions began to fall. But to our surprise, we discovered a more complex mechanism hidden in the conveyor belt system involving mountain building, continental erosion, and burial of the remains of microscopic organisms on the seafloor.

The Hidden Cooling Effect of Slowing Tectonic Plates in the Cenozoic

Tectonic plates slow down due to collisions, which in turn leads to mountain building, such as the Himalayas and the Alps formed over the last 50 million years. This should have reduced volcanic CO₂ emissions, but instead our carbon conveyor belt model revealed increased emissions.

We tracked their source to carbon-rich deep-sea sediments being pushed downwards to feed volcanoes, increasing CO₂ emissions and canceling out the effect of slowing plates.

Be Part of the Future

Sign up to receive top stories about groundbreaking technologies and visionary thinkers from SingularityHub.

So what exactly was the mechanism responsible for the drop in atmospheric CO₂?

The answer lies in the mountains that were responsible for slowing down the plates in the first place and in carbon storage in the deep sea.

As soon as mountains form, they start being eroded. Rainwater containing CO₂ reacts with a range of mountain rocks, breaking them down. Rivers carry the dissolved minerals into the sea. Marine organisms then use the dissolved products to build their shells, which ultimately become a part of carbon-rich marine sediments.

As new mountain chains formed, more rocks were eroded, speeding up this process. Massive amounts of CO₂ were stored away and the planet cooled, even though some of these sediments were subducted with their carbon degassing via arc volcanoes.

The limestone of the White Cliffs of Dover is an example of carbon-rich marine sediment, composed of the remains of tiny calcium carbonate skeletons of marine plankton. Image Credit: I Giel / Wikimedia, CC BY

Rock Weathering as a Possible Carbon Dioxide Removal Technology

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) says large-scale deployment of carbon dioxide removal methods is “unavoidable” if the world is to reach net-zero greenhouse gas emissions.

The weathering of igneous rocks, especially rocks like basalt containing a mineral called olivine, is very efficient in reducing atmospheric CO₂. Spreading olivine on beaches could absorb up to a trillion tons of CO₂ from the atmosphere according to some estimates.

The speed of current human-induced warming is such that reducing our carbon emissions very quickly is essential to avoid catastrophic global warming. But geological processes, with some human help, may also have their role in maintaining Earth’s “Goldilocks” climate.![]()

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Image Credit: David Mark from Pixabay

I am an Earth scientist interested in assimilating the wealth of geological and geophysical data into a four-dimensional Earth model (through space and deep time), connecting solid Earth to surface processes. I received my undergraduate degree in geology/geophysics from the Christian-Albrechts University of Kiel, Germany, and my PhD in Earth Science from the Scripps Institution of Oceanography, UC San Diego, California. After joining the University of Sydney in 1993 I built the EarthByte Research Group. The EarthByters are pursuing open innovation, involving the collaborative development of open-source software as well as open-access global digital data sets and virtual globes. Our fundamental aim is data synthesis through space and time, assimilating the wealth of disparate geodata into a virtual experimental planet.

Related Articles

This Brain Pattern Could Signal the Moment Consciousness Slips Away

Vast ‘Blobs’ of Rock Have Stabilized Earth’s Magnetic Field for Hundreds of Millions of Years

Your Genes Determine How Long You’ll Live Far More Than Previously Thought

What we’re reading