The Psychology of Olympians and How They Master Their Minds to Perform

Share

Participating in the Olympic Games is a rare achievement, and the pressures and stressors that come with it are unique. Whether an athlete is battling to win the breaststroke or powering their way to gold in the modern pentathlon, psychology will play a vital role in their success or failure in Paris this summer.

In recent Olympics, we have seen the mental toll that competing at the highest level can have on athletes. US gymnast Simone Biles withdrew from five events at the 2020 Tokyo Olympics to protect her mental health, and 23-time gold medal winner Michael Phelps has described the mental crash that hits him after competing in the Games.

When even small errors can cost them a medal, how do athletes use psychological principles to master their minds and perform under pressure?

Resilience

The ability to recover from setbacks, such as disappointing performances or injury is crucial. The role of mental processes and behavior such as emotional regulation (recognizing and controlling emotions such as anxiety) allows Olympians to maintain focus and determination amid the global scrutiny that comes with competing on the world’s biggest stage.

Resilience is not a fixed trait but rather a dynamic process that evolves through an interplay between individual characteristics, such as personality and psychological skills, and environment, such as an athlete’s social support. A 2012 study made in the UK investigating resilience in Olympic champions highlighted that a range of psychological factors such as positive personality, motivation, confidence, and focus as well feeling like they have social support helped to protect athletes from the potential negative stressors caused by competing in the Olympics. These factors helped to increase an athlete’s resilience and the likelihood they would perform at their best.

Social support means that athletes don’t have to feel like they are going it alone. If they can call on strong networks of family, friends, and coaches, it provides them with additional emotional strength and motivation.

Resilience empowers Olympians to draw upon individual skills and traits and protects them from the negative effects of stressors that inevitably come with competing in the Olympics. For example, a rower may need to solve problems such as changing weather conditions. Resilience allows them to maintain composure and adjust to the conditions, for instance by modifying their stroke technique.

Being Present

Staying in the present can help athletes avoid being overwhelmed or consumed by the significance of their event or distracted by the disappointment of past failures and the pressure of high medal expectations.

To help them remain in the present moment, athletes may use a variety of strategies. Mindfulness-based meditation and breathing exercises can help athletes feel calm and focused. They may also use performance visualization to rehearse specific movements or routines. Think of a basketball player visualizing a free-throw shot.

Be Part of the Future

Sign up to receive top stories about groundbreaking technologies and visionary thinkers from SingularityHub.

Similarly, many athletes will have well-rehearsed pre-performance routines which can create a sense of normality and control. For example, a tennis player may bounce the ball a certain number of times before serving. Staying in the present will help reduce athletes' anxiety, maintain focus on the task, and allow them to fully experience (and hopefully enjoy) the atmosphere.

Protecting Their Mental Wellbeing

Failure can be devastating and athletes can have complicated relationships with winning. For example, some athletes experience post-Olympic blues, which is often described as the feeling of emptiness, loss of self-worth, and even depression following an Olympic Games, even if the athlete has won a medal. British cyclist Victoria Pendleton wrote for The Telegraph in 2016 describing this phenomenon: “It’s almost easier to come second because you have something to aim for when you finish. When you win, you suddenly feel lost.”

Olympians may be champions, but like the rest of us, they will need to prioritize the fundamentals such as getting adequate sleep and downtime to recharge mentally. An Australian study conducted in 2020 highlighted the relationship between maintaining mental wellbeing and increased athletic performance. To ensure this, Olympians will be working closely with support staff such as performance nutritionists who will ensure they have a balanced diet which meets the physical needs of their event, helping to protect both physical and mental health.

They will also be working with sport and exercise psychologists throughout their training in preparation for the Olympics to manage challenges as and when they experience them. If an athlete starts struggling with performance anxiety ahead of the Games, they may practice mindfulness or cognitive restructuring, which are techniques that help people to notice and change negative thinking patterns.

Olympians and their support team will need to take care of both the person and the athlete to protect their wellbeing. When they protect their wellbeing, they are offering the best chance of both achieving their best performance during the Games themselves and avoiding the post-Olympic blues when they are over.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Image Credit: Jacob Rice / Unsplash

Mike is program lead and senior lecturer in sport and exercise psychology at Keele University. He is also a HCPC registered sport and exercise psychologist and chartered psychologist with the British Psychological Society (BPS). Mike joined Keele University in January 2024. Prior to this he worked as a senior lecturer in sport and exercise psychology at Edge Hill University. As an applied practitioner, Mike has extensive experience working with elite athletes and high-performance teams across a range of sports, specializing in football, cricket, darts, and golf. Mike is also currently an associate editor for the International Journal of Sport Psychology and committee member for the Division of Sport and Exercise Psychology (DSEP).

Related Articles

This Brain Pattern Could Signal the Moment Consciousness Slips Away

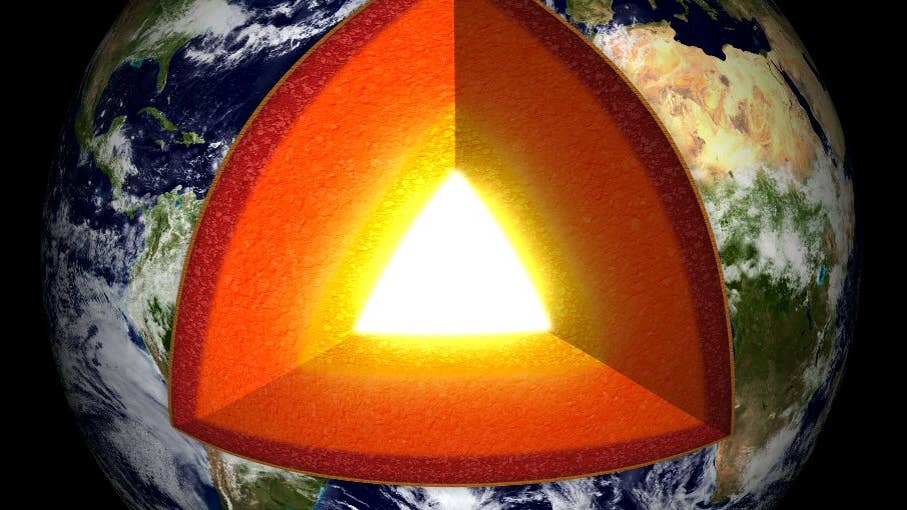

Vast ‘Blobs’ of Rock Have Stabilized Earth’s Magnetic Field for Hundreds of Millions of Years

Your Genes Determine How Long You’ll Live Far More Than Previously Thought

What we’re reading