Kids With Spinal Muscular Atrophy Show Dramatic Improvement With FDA-Approved Gene Therapy

Once only available for children under two, a one-and-done treatment is now approved for older kids too.

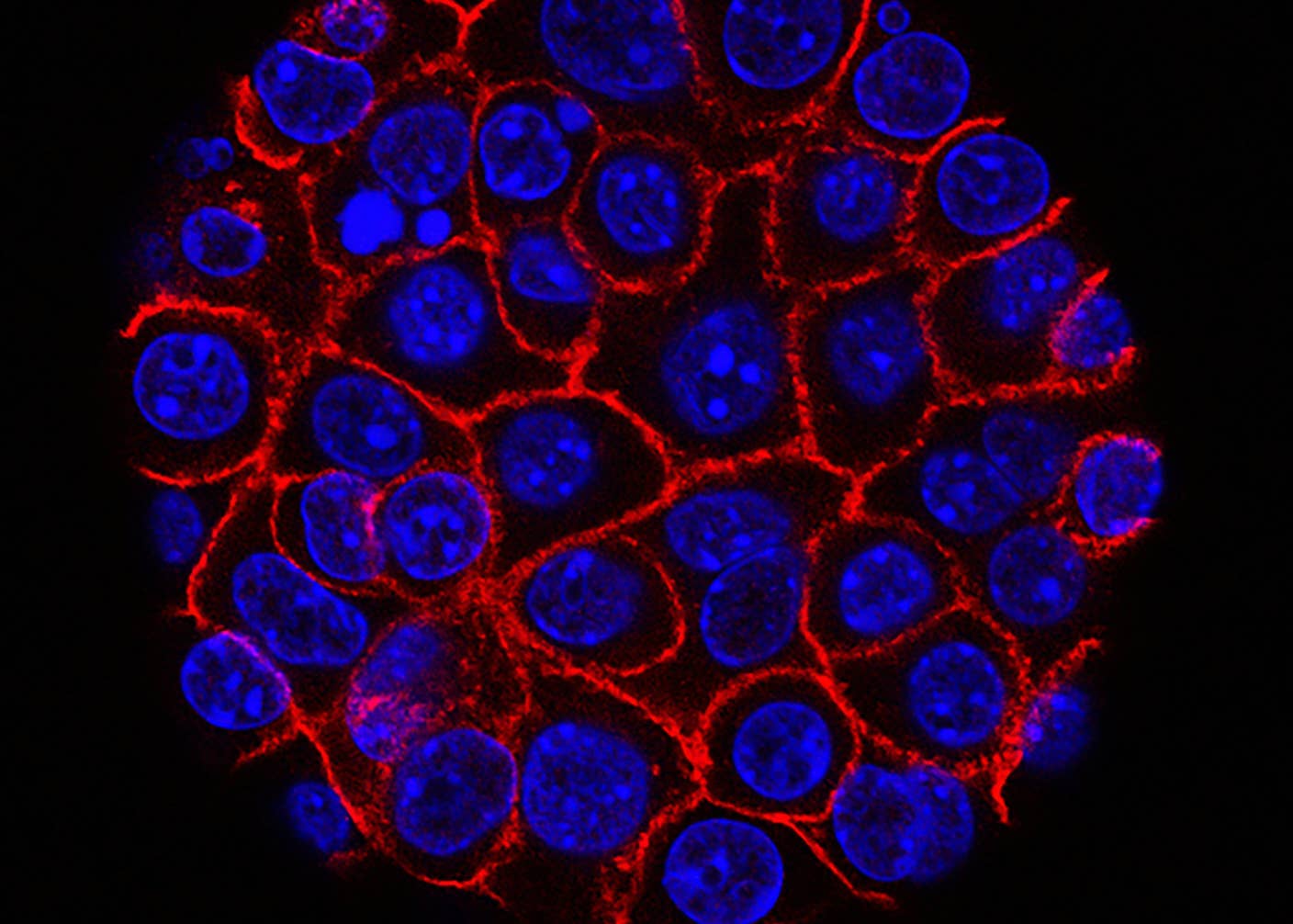

Image Credit

Arturo Esparza on Unsplash

Share

Waking up, hopping out of the bed, and stumbling to the kitchen for a cup of coffee: It’s an everyday routine most people don’t think twice about.

But for children with spinal muscular atrophy, simply propping themselves up in bed is an everyday struggle. The inherited disease is caused by mutations in the SMN1 gene. Without a working copy of the gene, motor neurons—cells that control muscles—rapidly wither.

Symptoms occur early in life. In the most severe cases, six-month-old babies can’t sit up without help. Others struggle to crawl or walk. The disease doesn’t affect learning and other cognitive abilities. Babies with the condition soak in their surroundings, and their brains develop normally. All the while, the disease cruelly destroys their bodies.

Left untreated, muscle weakness expands to the lungs, potentially causing deadly breathing problems. If there’s a silver lining, it’s that the disease has a clear genetic foe to target. Thanks to gene therapy, three treatments, approved by the FDA, can halt the disease in its tracks—if a patient is under two years old.

There’s a reason for the age limit. After two, the disease has already damaged motor neurons to such a degree that the therapy is no longer helpful.

Not so fast, two international teams of physicians and scientists wrote in December.

The teams published highly promising results from separate trials testing an experimental gene therapy, called Itvisma, in kids between 2 and 18 years of age. The new therapy is based on a previously approved version made by the drug company Novartis. Both have the same gene-correcting ingredient but are administered differently. The original relies on a shot into the bloodstream. Itvisma is delivered directly into the spinal cord.

The two recent trials brought significant improvement in participants’ ability to move over the course of a year. From not being able to walk, treated kids were able to roll into a sitting position from lying down and climb stairs, compared to children who did not receive treatment.

The results “demonstrate clinical benefits across a broad…population with a wide range of ages and baseline motor functions,” wrote Richard Finkel at St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital and team, on behalf of a broader STEER Study Group that conducted one of the trials.

The FDA agreed. In late November, the agency approved Itvisma for the disease, making it the only gene replacement therapy for people two years and older on the market.

“This achievement is not only a significant step forward for SMA [spinal muscular atrophy]–it also signals new possibilities for the broader field of neurological disorders and genetic medicine,” said John Day at the Stanford University School of Medicine in a Novartis press release.

Transformative Shot

Like its predecessor, Itvisma uses a harmless virus to carry a healthy version of the SMN1 gene into the body. The virus shuttles its cargo into cells but doesn’t tunnel into the genome. This makes it relatively safe, as it doesn’t raise the risk of unintended vandalism to the cell’s native DNA.

The previous therapy was a one-and-done shot into the bloodstream. The virus hitched a ride to motor neurons and restored their connection to muscle fibers. The liver and heart also received an unintentional dose, which could potentially cause side effects. Researchers carefully monitored children given the therapy for liver problems. These were relatively mild and easily treated.

The results were dramatic. Most treated infants were able to sit up, roll around in their cribs, and some could even crawl. But the treatment was only approved for children aged two years or younger.

Two problems hampered its broader use. One was timing: The disease rapidly eats away at motor neurons, causing long-term damage that’s difficult to restore. The other was safety. Gene therapies injected into blood are tailored to the recipient’s body weight—the higher the weight, the larger the required dose. Higher doses raise the risk of dangerous side effects, potentially causing the immune system to hyperactivate or cause damage to the liver.

For a toddler or teenager, the risk-benefit calculation didn’t work in the gene therapy’s favor.

Be Part of the Future

Sign up to receive top stories about groundbreaking technologies and visionary thinkers from SingularityHub.

Never Too Late

Itvisma took an audaciously different approach by injecting the gene therapy directly into the fluid surrounding the spinal cord.

The procedure is much more invasive than a standard shot, but has a unique edge. Gene therapies delivered in this way don’t depend on body weight. Rather, their effectiveness can be carefully calibrated in a single off-the-shelf dose for anyone with the disease—toddlers, teenagers, or even adults. And because the therapy mostly circulates in liquids surrounding the spinal cord and brain, it rarely reaches other organs to cause unexpected mayhem.

Two clinical trials validated the daring new strategy.

One trial, STRENGTH, recruited 27 participants with the disease between the ages of 2 and nearly 18. The main goal was to test the treatment’s safety. The trial was single-armed, meaning that all participants received the gene therapy without a control group.

Overall, Itvisma was found to be safe. Some participants experienced cold-like symptoms, such as a runny nose and a sore throat. Others reported temporary headaches and stomach discomfort. A few suffered more severe problems, like a temporary spike in liver toxicity, fever, and motor neuron problems, which eventually went away.

Giving all participants a working treatment can lead to placebo effects. So, a second trial, STEER, followed the “gold standard” of clinical trials: double-blind, randomized, and placebo-controlled. The trial recruited 126 participants from 14 countries but separated them into two groups. One received the gene therapy; the other went through the same injection procedure but without the treatment. Neither the patients, their families, nor their doctors knew who got an active dose.

A year later, patients given the gene therapy could stand up from sitting on the couch, and some climbed stairs without support. Those who didn’t receive the treatment fared far worse. Once the trial was unblinded—in that both patients and doctors knew who received what treatment—the control participants also got a dose of the gene therapy.

Results from both studies prompted the FDA to approve Itvisma for people older than two.

The “approval shows the power of gene therapies and offers treatment to patients across the…disease spectrum” including various ages, symptoms, and motor function levels, said Vinay Prasad, the FDA’s chief medical and scientific officer in an announcement.

Itvisma is the latest in a burgeoning field of one-and-done gene therapies this year. From tackling a devastating genetic disease that torpedoes normal metabolism to broadening gene editors for rare inherited diseases and slashing cholesterol to protect heart health, gene therapy is finally tackling diseases once deemed unsolvable. The momentum is only building.

Dr. Shelly Xuelai Fan is a neuroscientist-turned-science-writer. She's fascinated with research about the brain, AI, longevity, biotech, and especially their intersection. As a digital nomad, she enjoys exploring new cultures, local foods, and the great outdoors.

Related Articles

These Supercharged Immune Cells Completely Eliminated Solid Tumors in Mice

Souped-Up CRISPR Gene Editor Replicates and Spreads Like a Virus

Your Genes Determine How Long You’ll Live Far More Than Previously Thought

What we’re reading