Can Bacteria Fight Obesity? Gut Bacteria From Thin Humans Can Make Obese Mice Slim

Why are some people fat? It’s not just a question that fat people ask themselves, but also one that drives much medical research because obesity increases the risk of serious illnesses, including heart disease and diabetes. The proposed causes of obesity range from diet plain and simple to hormonal conditions to genetics. A study recently published in Science adds to that list gut bacteria.

Share

Why are some people fat? It’s not just a question that fat people ask themselves, but also one that drives much medical research because obesity increases the risk of serious illnesses including heart disease and diabetes.

A study recently published in Science adds gut bacteria to the list of possible causes of obesity.

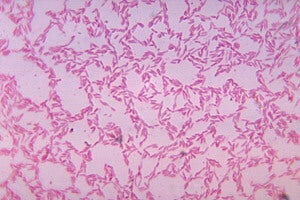

The intestine is home to trillions of microbes that help the body break down and use food. The particulars of the mix have been found to vary significantly from person to person, even among identical twins.

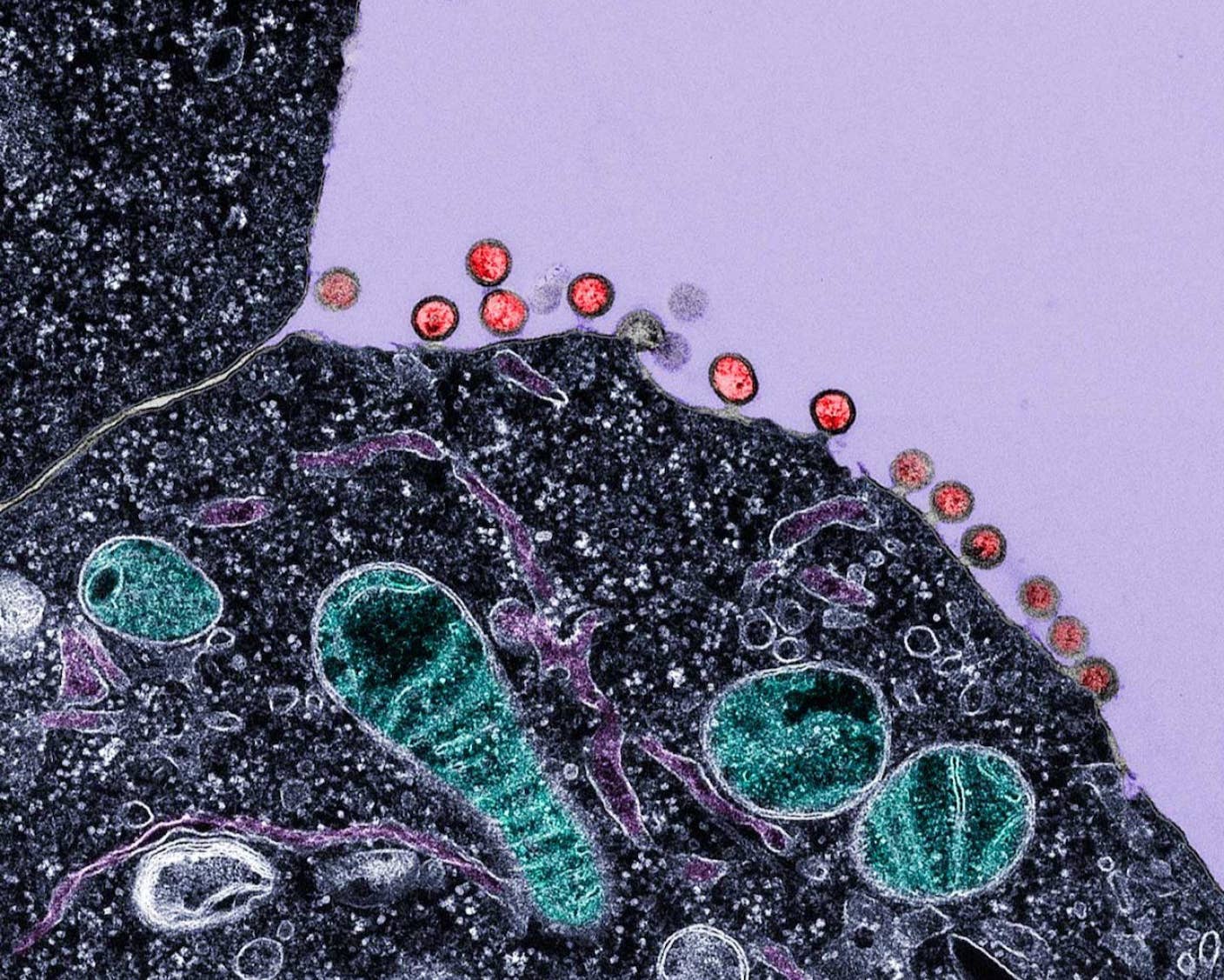

In an effort to isolate the contribution of gut bacteria to weight, researchers led by Jeffrey Gordon, of Washington University in St. Louis took the bacteria from pairs of identical and fraternal twins, each with one obese twin and one lean, and put it in previously germ-free cloned mice. (We glossed tastefully over the matter of the fecal transplant.)

The results indicate that bacteria does in fact play a powerful role: The mouse that got the obese twin’s bacteria grew fat and developed metabolic problems linked to insulin resistance, even when fed only low-fat mouse chow.

The researchers then housed the fat and thin mice together, allowing their gut bacteria to mix. (Mice housed in the same cage typically eat each other’s droppings.) The thin bacteria beat out the fat bacteria in the obese mice, and they became thin again.

So is obesity purely a question of gut bacteria? No such luck. The “thin” bacteria, specifically a group called Bacteroidetes, was only able to triumph when the fat mice were eating low-fat mouse chow. When they were fed a higher-fat food meant to mimic a typical American diet, obese mice kept the obese twin’s gut bacteria — and the excess weight.

Be Part of the Future

Sign up to receive top stories about groundbreaking technologies and visionary thinkers from SingularityHub.

“Eating a healthy diet encourages microbes associated with leanness to quickly become incorporated into the gut. But a diet high in saturated fat and low in fruits and vegetables thwarts the invasion of microbes associated with leanness. This is important as we look to develop next-generation probiotics as a treatment for obesity,” said Gordon.

It can’t be long before we see Bacteroidetes and other potentially thinning “probiotics” for sale in the supermarket next to green tea.

But, buyer beware, the mouse studies are far from conclusive. The next step for Gordon and his team will be growing microbes in the lab and mixing them to nail down which combinations have which metabolic effects.

“There’s intense interest in identifying microbes that could be used to treat diseases,” he said.

Especially diseases that make us fat.

Photos: Lexicon Genetics Incorporated via Wikimedia Commons; Gordon with graduate student and co-author Vanessa Ridaura, E. Holland Durando, Washington University of St. Louis; CDC via Wikimedia Commons

Cameron received degrees in Comparative Literature from Princeton and Cornell universities. He has worked at Mother Jones, SFGate and IDG News Service and been published in California Lawyer and SF Weekly. He lives, predictably, in SF.

Related Articles

Single Injection Transforms the Immune System Into a Cancer-Killing Machine

New Gene Drive Stops the Spread of Malaria—Without Killing Any Mosquitoes

New Immune Treatment May Suppress HIV—No Daily Pills Required

What we’re reading