They’re Alive! Watch These Mini 3D Printed Organs Beat Just Like Hearts

Share

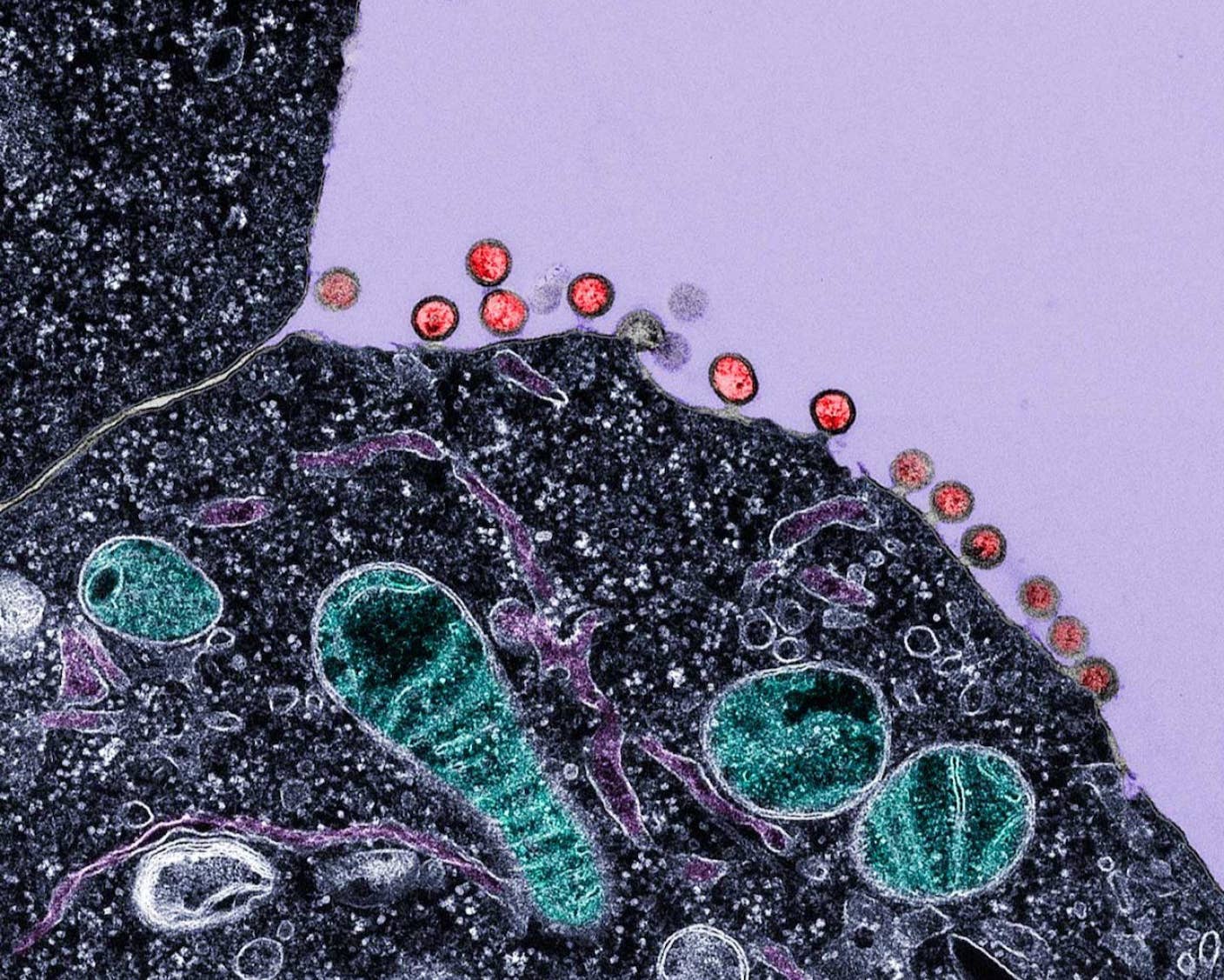

There’s something almost alchemical going on at the Wake Forest Institute for Regenerative Medicine. Scientists there have genetically transformed skin cells into heart cells and used them to 3D print mini-organs that beat just like your heart. Another darker organoid fused to a mini-heart mimics your liver.

The work, developed by Anthony Atala and his Wake Forest team for the “Body on a Chip” project, aims to simulate bodily systems by microfluidically linking up miniature organs—hearts, livers, blood vessels, and lungs—and testing new drug treatments and chemicals or studying the effects of viruses on them.

The research may reduce reliance on animal testing—a method that, in addition to being slow and costly, doesn’t necessarily yield results pertinent to humans. By screening drugs on human organoids prior to clinical trials, we may accelerate treatment discovery and increase the odds trials will prove successful.

Atala has been working on regenerative medicine for over 20 years. But he recently added 3D bioprinting to his arsenal. In a 2011 TED talk, he 3D printed a non-functioning kidney onstage (some 90% of patients on donor lists await a kidney). In addition to 3D printing, scientists like Atala are now able to genetically reprogram a patient's cells (often skin cells) to grow new tissue sourced directly from their own body.

Atala's team isn't alone in their quest. Others are working to make tissues and organs using 3D printers and cultured cells. Organovo, for example, is 3D printing miniature strips of human liver, and a University of Louisville team aiming to construct an entire human heart has begun printing valves and vasculature.

The holy grail, still years away, is the creation of fully functional organs comprised of a patient’s own cells. These could end long waits on organ donor lists and eliminate transplant rejections in one fell swoop.

Be Part of the Future

Sign up to receive top stories about groundbreaking technologies and visionary thinkers from SingularityHub.

Jason is editorial director at SingularityHub. He researched and wrote about finance and economics before moving on to science and technology. He's curious about pretty much everything, but especially loves learning about and sharing big ideas and advances in artificial intelligence, computing, robotics, biotech, neuroscience, and space.

Related Articles

Single Injection Transforms the Immune System Into a Cancer-Killing Machine

New Gene Drive Stops the Spread of Malaria—Without Killing Any Mosquitoes

New Immune Treatment May Suppress HIV—No Daily Pills Required

What we’re reading