Every year in the US, about five thousand babies are born with genetic or functional disorders that can be partly or completely treated through early detection. As amazing as it sounds, up until four years ago the United States had no standardized policy for proactively detecting and treating these thousands of children. Now, thanks to efforts from non-profit March of Dimes, every state in the country screens babies for at least 21 different diseases through a blood test the day they are born. This is nothing short of a revolution in human health and disease. Through a simple policy change, thousands of children’s lives have been vastly improved.

Of course the true goal is to eradicate genetic disorders before a baby is born, and technologies such as PGD that we have reported on earlier are allowing this to occur. But until this technology becomes widely available, early identification and treatment are our best options. According to a new report released by the March of Dimes, the last 4 years have seen a stunning improvement in this regard.”

“Today we announce that expanded screening is required by the states for nearly 100 percent of the more than 4 million babies born each year in the U.S.,” said Dr. Jennifer L. Howse, president of March of Dimes, in a press release last month.

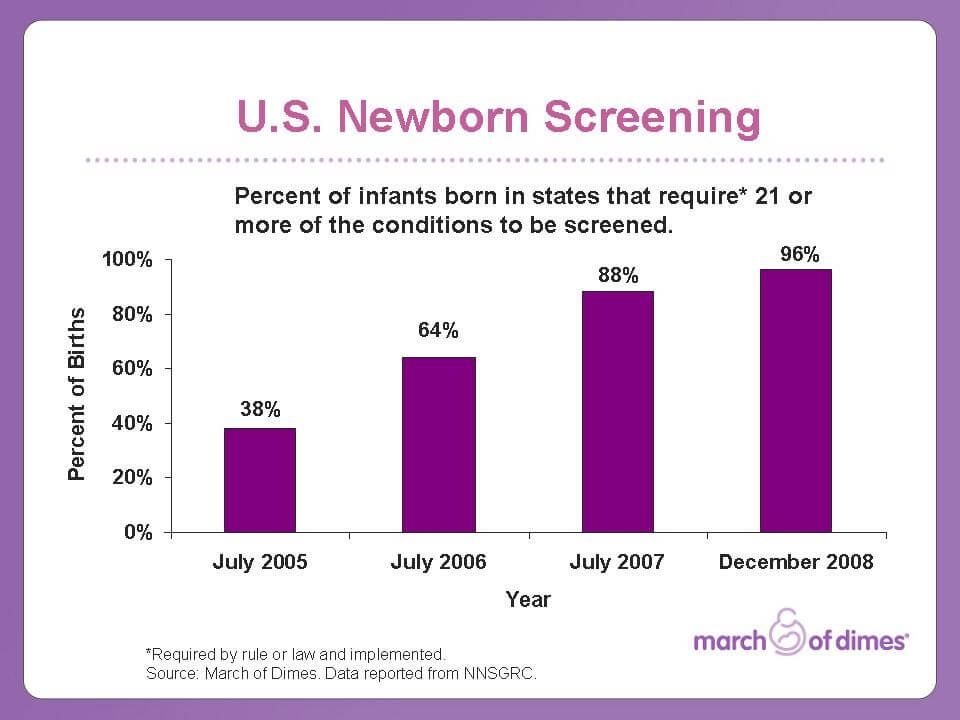

This is an outstanding achievement for public health policy. In 2005, the American College of Medical Genetics (ACMG) issued a report recommending mandatory screening for 29 “core” disorders. At that time, only 38 percent of newborns in the United States were screened for 21 or more of these disorders. Thanks largely to the advocacy of March of Dimes, every state now has laws or rules in place to require screenings of at least 21 of the disorders, though Pennsylvania and West Virginia have yet to fully implement their expanded programs. A full list of the disorders recommended for screening by the ACMG is available here.

Newborn screening is performed by taking a few drops of blood from an infant’s heel prior to discharging them from the hospital. Doctors test the blood for a variety of genetic and metabolic disorders that can pose serious risks to the infant’s health, including mental retardation, lifelong disabilities, and even death. Early detection means early treatment, which can dramatically improve the newborn’s health for a lifetime.

Most developed countries have newborn screening programs, though the list of disorders tested for varies widely across the globe. Many developing countries lack screening programs altogether. Thousands of children could benefit from the expansion and standardization of screening procedures internationally, especially given that some disorders can be treated with simple dietary changes. Imagine the lives that could be saved or improved throughout the world thanks to a simple blood test.

While newborn screening can diagnose a disease, it cannot undo it. New procedures like preimplantation genetic diagnosis (PGD) allow for genetic screening prior to implantation or fertilization. PGD is already used to prevent many of the same disorders diagnosed by newborn screening. As these procedures become more advanced, it will be possible to catch many disorders before a baby is born.

The success stories of newborn screening speak to its value, and the importance of consistent guidelines to make such an important technology available in every state.

The March of Dimes is a nonprofit organization dedicated to preventing birth defects and infant mortality. The March of Dimes will continue its role as a watchdog on screening, publishing report cards on states’ implementation of this vital practice. Parents can find further information on newborn screening here.