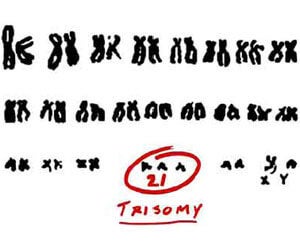

Simple Blood Test Now Detects Prenatal Down Syndrome

Share

Things are definitely on the move in the field of fetal screening. Researchers at the Cyprus Institute of Neurology and Genetics have developed a test that analyzes maternal blood between 11 to 14 weeks of gestation for the presence of fetal trisomy 21, the occurrence of an extra chromosome primarily responsible for Down syndrome. Not only is it an improvement on other methods, it is noninvasive, eliminates screening by amniocentesis, and is 100% accurate. If the results of an early trial can be replicated, a commercial test may be available in a couple of years. This is a welcome addition to the growing arsenal of technologies aimed at turning the tide against genetic disease.

Thankfully, we’re getting closer to the day when those 5-inch needles can be a thing of the past.

Genetic disorders are a broad and complex set of abnormalities in an individual’s DNA that can be evident in the womb or lay hidden until a later point in life. Down syndrome is one of the former and is the most common chromosomal condition, affecting one in every 691 babies. While it is most commonly associated with a characteristic physical appearance, other aspects of the syndrome can vary significantly from one individual to another, such as developmental delays, impairments in physical growth, and a range of other health issues, some life threatening. Nowadays, expectant mothers are warned about the possibility of Down syndrome especially because the risk for Down syndrome rises abruptly with age. In fact, the incidence rate increases from 1 in 1,250 at age 25 to 1 in 106 at age 40, and by age 49, that risk is 1 in 11.

It is now standard to recommend midtrimester amniocentesis for women over the age of 35 and some doctors are urging all pregnancies to be screened for trisomy 21. And that’s where the problem comes in. Inserting a needle into the amniotic sac to withdraw fluid turns out to be kind of risky (who would have thought?). Infection can occur, the fetus could be punctured, or labor could be induced. These risks accumulated into a miscarriage rate of about 1 out of every 200 pregnancies, although current studies suggest that improvements in procedure and the use of ultrasound has lowered that number to 1 in 1,600 pregnancies. Still, everyone can agree that a screening procedure shouldn’t be as risky as the condition it is testing for.

Clearly, Dr. Philippos Patsalis and his colleagues in Cyprus felt that there was a better way, so they started with a discovery 15 years ago that significant amounts of fetal DNA (3-6%) circulates within a pregnant woman’s blood. The presence of an extra 21st chromosome could be important if they could find signatures within it that could be contrasted against the mother’s DNA. Fortunately, the researchers found eight sites on the extra chromosome that have higher degrees of cytosine methylation. By amplifying the fetal DNA, screening for the higher methylation and running statistical analysis, they were able to detect trisomy 21 in maternal blood in two groups (one control and one blind) of 40 pregnant women with 100% sensitivity and 100% specificity. Additionally, the blood was obtained between 11 and 14 weeks of gestation, which is up to a month earlier than a reliable amniocentesis can be performed. And here’s another cool thing: the methodology uses techniques that are common to many diagnostic laboratories, and that means a low implementation and a low cost. Admittedly, this was a small trial and Dr. Patsalis has stated that a larger clinical trial is needed, but clearly this is moving in the right direction.

Be Part of the Future

Sign up to receive top stories about groundbreaking technologies and visionary thinkers from SingularityHub.

This new methodology not only reflects the power and potential of genetics screening, but it adds to the arsenal of prenatal knowledge that healthcare professionals and parents are gaining access to and at an earlier stage in gestation. A few years ago, we highlighted some of this progress with preimplantation genetic diagnosis for IVF embryos, but for parents who’ve gone about making babies the low tech way, earlier detection is important for making decisions about lifestyles. Let’s face it: raising a child with a genetic disorder can be daunting and many who discover the presence of trisomy 21 opt to terminate the pregnancy, as much as 92 percent in the UK. Ethics aside, this new test for Down syndrome will hopefully become part of the multitude of prenatal genetic conditions that are currently part of standard screens. Considering that 1 in 5 women have their first children after age 35, a new test can’t come soon enough.

[Image: National Institute of General Medical Sciences]

[Source: March of Dimes, National Down Syndrome Society, Nature Medicine, NY Times]

David started writing for Singularity Hub in 2011 and served as editor-in-chief of the site from 2014 to 2017 and SU vice president of faculty, content, and curriculum from 2017 to 2019. His interests cover digital education, publishing, and media, but he'll always be a chemist at heart.

Related Articles

This Week’s Awesome Tech Stories From Around the Web (Through March 7)

Autonomous AI Agents Have an Ethics Problem

Thousands of Everyday Drone Pilots Are Making a Google Street View From Above

What we’re reading