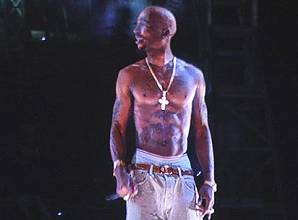

Just a week after Easter, Coachella music festival was shaken by the ghostly visage of slain rapper Tupac Shakur, resurrected to strut the stage for five surreal minutes, leaving the crowd stunned. It is now well known that this hip-hop apparition was a product of both state-of-the-art computer graphics and antiquated stage tricks. However, the source of the erstwhile rapper’s unmistakable voice – which shouted “what the f*** is up Coachella?!” to a festival that didn’t exist until three years after his 1996 murder – is still unclear. It’s possible that ‘Pac’s pronouncements were invoked by way of speech synthesis, digital mimicry of the human voice. “The underlying technology is somewhat freely available and with enough time, I believe it would be possible to synthesize a new song by hand,” says Alan Black, Associate Professor at Carnegie Mellon’s Language Technologies Institute. “I sort of think that’s what happened here.”

Experimenters have sought to recreate and control the sounds of speech for centuries, processing snippets of recorded voices, manipulating signals, and modeling the human vocal tract – sometimes with unsettling results. These days, a common approach involves building digital libraries of recorded phonemes (‘Shakur,’ for example, can be broken into five phonemes: ‘Sh,’ ‘a,’ ‘k,’ ‘u,’ and ‘r’), which are recombined and treated with vibrato, pitch, and breath to synthesize human utterances. This is called “concatenative synthesis,” and the process is refined enough that a new translation program by Microsoft can do it automatically. After an hour of getting familiar, the software will translate a user’s words among 26 languages, in their speaking voice.

A similar process also drives the daily conversations between iPhone users and Siri, Apple’s chatty digital assistant. The source voice of Siri is undisclosed except in the UK, but wide public acceptance of conversational tech reveals how ready we are to recognize the personalities of even artificial speakers. The sound of the dated synthesizer that allows famed astrophysicist Stephen Hawking to communicate is so inevitably tied to his public identity, his technician was reluctant to upgrade to more realistic synthetic voices now available.

Meanwhile, the speech patterns of dearly departed voices are being painstakingly recreated, as with the beloved Japanese entertainer Hitoshi Ueki, aspiring for total realism in vocaloid form. Years before Coachella, holographic superstars have been performing fan-generated songs to sold-out arenas in Japan and the States, a full-blown pop phenomenon powered by voice synthesis. Chart-topping “E-Diva” Hatsune Miku is the most popular of this growing troupe of singing, dancing vocaloids, whose digital intonations stir fans as surely as Lady GaGa or Katy Perry (themselves arguably examples of speech synthesis).

When IBM’s DeepQA computer Watson was equipped with a soothing voice synth and let loose on Jeopardy, we were offered a glimpse at the potential power of a computer brain with the ability of human speech. Even the game show’s counter-intuitive format and questions ripe with puns and wordplay rarely tripped up Watson, always addressed by name, always listening and ready to speak up. Talking to machines can seem downright natural when we feel that we are exchanging more than mere data, even if the sense of true communication is, at this point, only illusory.

When crowds are brought to their feet by what basically amounts to an overhead projector, and frustration peaks as we and our devices misunderstand one another, granting machines our most fundamental form of communication is leading to a more complicated relationship, and may indeed signal a burgeoning conversation. While we might not expect thrilling repartee with a synthetic voice for some time, it’s clear that as our computers learn their first words we are beginning to recognize their voices.

About The Author: Doug Bierend is a Los Angeles based writer interested in technology, culture, and where they intersect