“Good” Cholesterol Not So Good After All, New Study Shows

Share

The revelation that high-density lipoprotein, or HDL, is the “good cholesterol” has suffered a major blow. A meta-study involving over a hundred thousand participants used two different strategies to see if genetic mutations that increased levels of HDL also decreased risk for heart disease. In both cases the answer was a resounding no. The researchers were shocked when they saw the data. Now it’s their turn to shock HDL proponents and drug companies looking to cash in on the HDL craze.

The study, which was published recently in The Lancet, is causing quite a stir in the field. As Dr. James de Lemos, from the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, told the New York Times, “I’d say the HDL hypothesis is on the ropes right now.” Dr. de Lemos was not involved in the study.

So what’s the story here? How is it possible that LDL/HDL dichotomy has propagated so powerfully through conventional wisdom that even the CDC refers to them as “good” and “bad” cholesterols and pharmaceutical companies like Abbot Laboratories are working hard to get in on the HDL cash cow?

Past studies have shown that much of what increases our risk for heart disease, like obesity, lack of exercise, smoking, and insulin resistance, is correlated with low HDL. It was a logical conclusion, then, that by increased HDL levels we could decrease those risks. But correlation doesn’t mean causation, and the takeaway conclusion from the current study is that decreased HDL is simply a sign of increased risk for heart disease but the level of HDL doesn’t actually affect heart disease.

In the most recently published study researchers used genetic, lipoprotein, and heart attack outcome data from some thirty odd studies to see if a genetic mutation known to increase HDL levels decreased the chance of heart attack. They focused on the gene for endothelial lipase. Past research has shown that when endothelial lipase has certain single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) it leads to increased levels of HDL. Looking at study data from 116,000 participants, they saw that 2.6 percent of them had the SNPs and confirmed that their HDL levels were significantly higher than average. But when they compared the incidence of heart attack between the two groups they found no difference whatsoever.

The second part of the study took a similar approach, but instead of limiting analysis to one gene the researchers looked at 14 gene variants know to affect HDL levels and asked if the variations affected cardiovascular health. Again, the amount of HDL did not affect whether or not a person suffered a heart attack.

But even with such a high sample size, it’s possible that the methodology of the study was somehow flawed. Using low-density lipoprotein (LDL) - the so-called bad cholesterol - as a control, the researchers analyzed gene variants among the participant pool and confirmed that decreased levels of LDL lessened the chance of a heart attack, validating their analysis of the HDL data.

Be Part of the Future

Sign up to receive top stories about groundbreaking technologies and visionary thinkers from SingularityHub.

This may come as a shock to many, but another study published last year suggested that HDL was not so “good” after all. The trial tested the effects of niacin, a drug that increases a person’s HDL levels, on over 3,000 patients at risk for heart disease. Because niacin stimulates the production of HDLs they were expected to improve the cardiovascular outlook of these high-risk patients. Two years into the study researchers confirmed that the group’s HDL levels were increased. At three years, however, the study was stopped prematurely due to “lack of efficacy.”

But while the research may be “on the ropes,” not everyone’s throwing in the HDL towel just yet. Dr. Steven Nissen who is the Cleveland Clinic’s chair of cardiovascular medicine and conducts HDL research himself told the New York Times that he is “hopeful,” reasoning that HDL is “complicated.” In 2010 the Cleveland Clinic received a $11.6 million grant to study the benefits of HDL, so it’s easy to see how the current study would indeed “complicate” things.

Cardiovascular disease is the world’s number one killer. Responsible for 30 percent of all deaths globally, it claimed the lives of nearly 16 million people in 2008. The pharmaceutical giants all have their own version of cholesterol-lowering statin: Merck’s Zocor, AstraZeneca’s Crestor, and Pfizer’s Lipitor, which has become the most profitable drug of all time at sales of over $130 billion. It’s no wonder then that companies have been busy trying to reap the rewards of HDL-boosting niacin.

Abbott Laboratories, which offers a version of niacin called Niaspan, responded to the halted trial by saying it might not work for the chronically high-risk, but it remains to be seen if others won’t benefit. But like Dr. Nissen, I suppose Abbott can take momentary solace in the fact that these are, after all, just two studies – albeit one a very large study. But if others begin to confirm the current findings, the “good” in HDL will become “good riddance.”

[image credits: Healthy Living, DoctorSaputo.com, and Benefits of Niacin]

images: Healthy Living, DoctorSaputo.com, and Benefits of Niacin

Peter Murray was born in Boston in 1973. He earned a PhD in neuroscience at the University of Maryland, Baltimore studying gene expression in the neocortex. Following his dissertation work he spent three years as a post-doctoral fellow at the same university studying brain mechanisms of pain and motor control. He completed a collection of short stories in 2010 and has been writing for Singularity Hub since March 2011.

Related Articles

This Week’s Awesome Tech Stories From Around the Web (Through February 7)

Scientists Want to Give ChatGPT an Inner Monologue to Improve Its ‘Thinking’

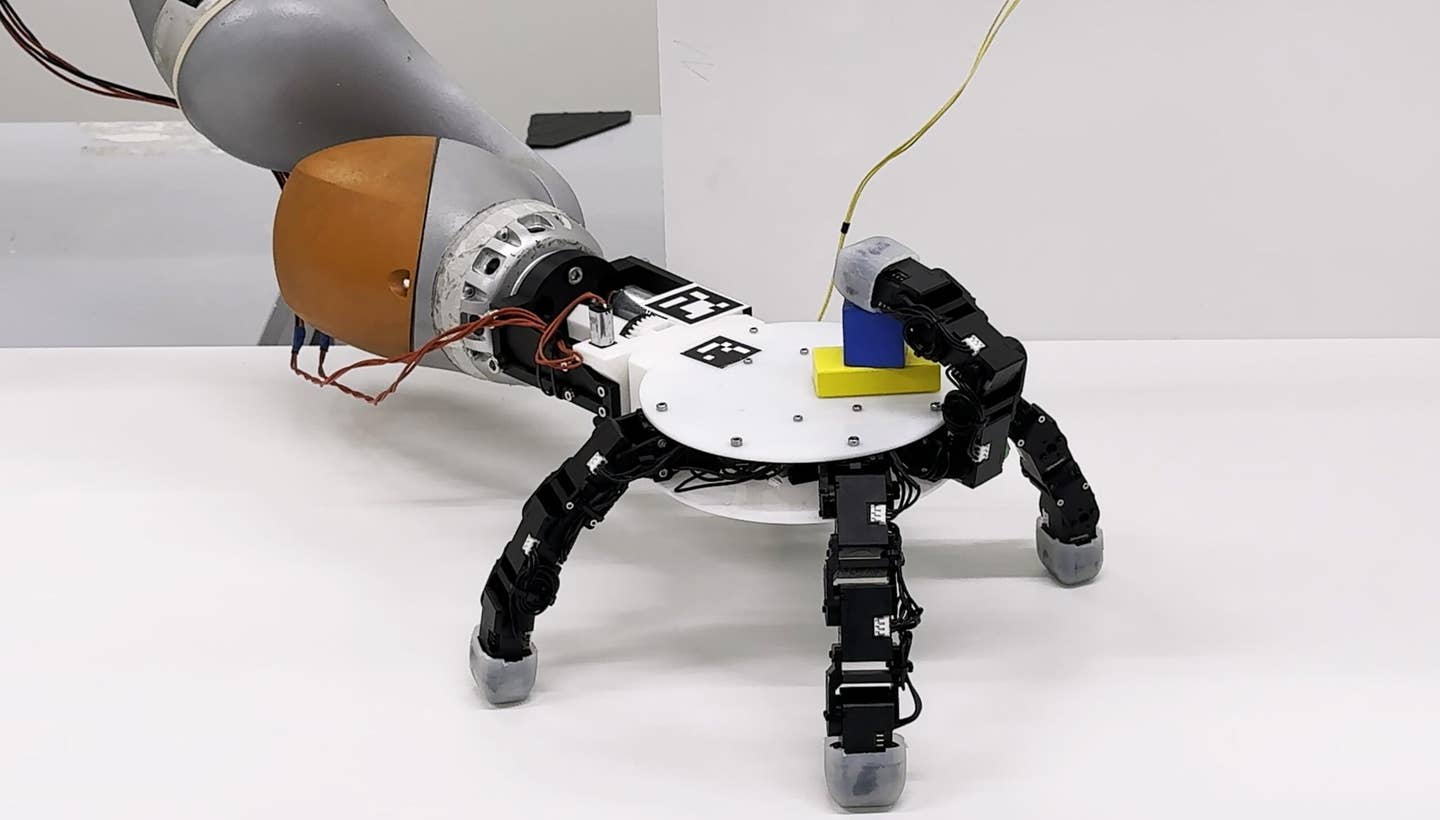

This Robotic Hand Detaches and Skitters About Like Thing From ‘The Addams Family’

What we’re reading