What kind of movement would Facebook creator Mark Zuckerberg, Twitter founder Jack Dorsey, Gabe Newell of Valve, and Microsoft’s Bill Gates all back enthusiastically? A call for more computer programmers, specifically really young ones.

The nonprofit organization Code.org recently commissioned a short film titled What Most Schools Don’t Teach that profiled some of the most recognizable names in technology, along with musician will.i.am and Chris Bosh of the Miami Heat, to put out a call to get kids excited about something that is shrouded in geekitude: computer programming. In the short video, each technophile takes their turn diffusing some misconceptions about learning to program and relating what coding means to them personally.

For example, Zuckerberg relays his own programming in his early days: “Learning how to program didn’t start off as wanting to learn all of computer science, or trying to master this discipline, or anything like that. It just started off because I wanted to do this one simple thing: I wanted to make something that was fun for myself and my sisters.” He added, “I wrote this little program and then basically added a little bit to it. When I needed to learn something new, I looked it up in a book or on the Internet, and just added a little bit to it.”

The film strongly drives home two main messages: coding is not as hard/geeky/foreign as you think and it’s as vital to your future career as any subject in school (perhaps more so). Considering how rapidly automation is replacing jobs, coding offers both a way for future generations to stay competitive as well as contribute to the revolution that will make new technologies like robots commonplace.

Check out the video to see for yourself:

Code.org has the solitary mission of “growing computer programming education,” and toward this end, getting superstar endorsements is an important marketing strategy. In fact, the video is only a sampling of people in the world of technology, politics, and entertainment that have given their support to code.org’s cause. The front page of the site includes a long list of quotes reiterating the importance of teaching a generation of kids to program. The site also allows teachers to sign up in order to find ways to bring programming courses to their schools.

Fortunately, learning to code is now easier than ever. Beyond the numerous tutorials that are freely available for programming languages, such as Python, numerous sites have sprung up to teach coding, such as the kid-friendly Scratch, the lessons from Codecademy, and the ever popular Khan Academy. Additionally, new approaches for learning to code include Code Racer, which uses a racing game to teach coding.

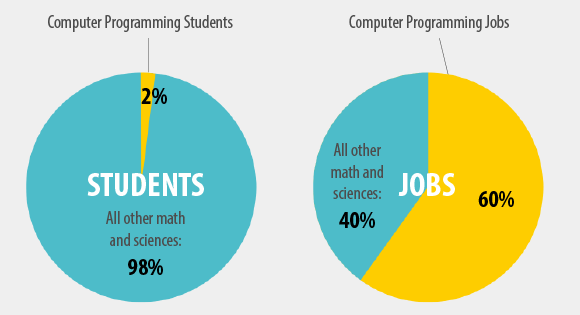

Access to programming education is vital because, as the video drives home, the demand for computer programming skills will only be increasing in the future. Code.org estimates that by 2020 there will be a surplus of a million computer jobs beyond what the approximately 400,000 computer science students will occupy. At the same time, only one in 10 schools offers computer programming classes.

Though it is helpful to see the deconstruction of each of these tech leaders’ experience with coding, it is also noteworthy that many got introduced to the subject in school, but at some point started down a path of self learning. It is one of the challenges of modern education to emphasize teaching a subject that the superstars will inevitably learn mostly out of the classroom.

Perhaps the real problem with how educators view computer programming is that it is framed within the context of computer science. Coding, in many ways, is much more like a language course, except that one learns to communicate with a computer rather that a person. Because a computer only thinks and expresses itself in certain ways, learning to speak to it involves breaking down what you want it to do in logical instructions, and then looking for feedback from it to make sure it comprehends.

At its heart, coding is an amalgam of skills that are rarely taught directly, but students pick up from various formal coursework or from simply learning it themselves through trial-and-error, much as other creative types like writers and artists do.

Computer science, on the other hand, falls into more traditional courses of mathematics and science and crosses into areas like electronics (physics), organizational patterns (biology), number crunching (statistics), and computer architecture (engineering). That isn’t to say coding and computer science don’t overlap — obviously, they are interdependent disciplines — but it is to say that when people talk about the “art of coding,” they are referring to a much different way of thinking than is emphasized in science and math education.

The proliferation of technology in future decades suggests something even more pressing: coding even at the most basic level may be a prerequisite to being a member of society. After all, if machines in various forms will be abundant, then the communication concepts within programming will be exercised as part of daily life.

The coming age of robots will be a lot like an alien race that suddenly moved to Earth to co-habitate with us. If we know in advance that this is going to happen, it only makes sense that we should learn how to speak to them and soon.