Gene Therapy Helps Parkinson’s Patients, But Is It Simply A Placebo?

Even with promising results in humans paired with dramatic results in earlier tests in primates, a gene therapy treating Parkinson's disease, first developed in 1997, is heading back to the drawing board. Here's why.

Share

Since the heady days of the initial human genome sequencing, doctors have pointed to the prospect of administering the “right” version of a gene to patients suffering from genetic diseases to affect miracle cures like those seen in “Awakenings” — but permanent.

A genetic treatment for Parkinson’s disease shows just how close and, at the same time, how far medicine now is from such miracle cures.

The same drug seen in the 1990 movie — L-dopa, which the body converts into the neurotransmitter dopamine — now serves as the gold-standard for Parkinson’s disease. Because it treats the symptoms rather than the underlying cause, its effects eventually dwindle in the face of progressing neurological damage. It can also cause tics and involuntary movements.

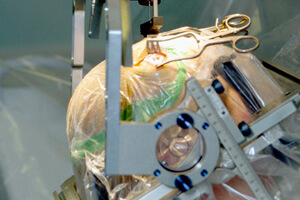

The genetic therapy pioneered by Nicholas Mazarakis, of the Imperial College in London, has sought to offer patients relief without the side effects by prompting the body to make its own dopamine. Doctors inject genes, wrapped in a lentivirus, that drive dopamine production into the region of the brain that controls movement. The drug is being commercialized by Oxford BioMedica as ProSavin.

The method was recently tested for the first time on 15 human patients suffering from advanced Parkinson’s disease, and all saw improvements on a standard test measuring movement-related symptoms, with a mean decline of 30 percent. PET scans showed more dopamine production, and none of the patients experienced major adverse reactions. Results of the trial, funded by the company seeking to market the therapy, were published in The Lancet.

“I’m very pleased that it has appeared to work in the clinic. It has the potential to move to the next phase. It needs to be done in more people; we have to find the most effective dose, to further increase efficacy, and prove beyond doubt that this is not a placebo effect,” Mazarakis said in a news release.

Be Part of the Future

Sign up to receive top stories about groundbreaking technologies and visionary thinkers from SingularityHub.

Mazrakis’s enthusiasm was muted because the improvements observed in the trial were “within the placebo range reported in other clinical trials for Parkinson’s disease using surgical techniques,” according to the study. It’s therefore not clear whether the therapy, which requires brain surgery, worked or not.

“All the participants knew they were receiving the treatment, and it is well known that surgical treatments create a large placebo effect that can last for more than 12 months. Simply placing lesions in the basal ganglia regions of the brain can help the motor symptoms of Parkinson’s and it is possible that the improvement seen was a result of the surgical procedure itself rather than the novel gene therapy,” the Parkinson’s Disease Foundation stated about the findings on its website.

Even with promising results in humans paired with dramatic results in earlier tests in primates, ProSavin, first developed in 1997, is heading back to the drawing board. Researchers will tweak the dosage and the delivery method in hopes of proving in subsequent randomized human trials that its effects exceed those of a placebo.

Meanwhile, an alternative gene therapy that delivers the GAD gene is also moving through clinical trials, and electronic stimulation to the brain is emerging as a way to augment the effects of levodopa to control the devastating symptoms of a disease that affects more than 7 million people worldwide.

Photos: Imperial College, Paul Hudson via Flickr, Thomasbg via Wikimedia Commons

Cameron received degrees in Comparative Literature from Princeton and Cornell universities. He has worked at Mother Jones, SFGate and IDG News Service and been published in California Lawyer and SF Weekly. He lives, predictably, in SF.

Related Articles

Single Injection Transforms the Immune System Into a Cancer-Killing Machine

This Light-Powered AI Chip Is 100x Faster Than a Top Nvidia GPU

This Week’s Awesome Tech Stories From Around the Web (Through December 20)

What we’re reading