Virtual Arm Eases Amputee’s Phantom Limb Pain

Swedish researchers created an augmented reality system in which myoelectric electrodes on an amputee patient's stump indicated his attempted muscle movements for the missing arm, and an arm image on screen reflected those movements back to him. The patient reported that his chronic phantom limb pain diminished dramatically.

Share

It would be hard enough to learn, as a patient in a hospital, that doctors would have to amputate a limb. But imagine losing the limb only to have it replaced by constant chronic pain. Phantom limb pain affects up to 7 in 10 amputees.

One such amputee, a 72-year-old Swedish man had experienced constant pain from his missing arm since it was amputated below the elbow following a traumatic injury in 1965. He was regularly jolted from sleep by the pain. Drugs, acupuncture, hypnosis: None worked.

The patient, unnamed in the study but identified by the BBC as Ture Johanson, also underwent mirror therapy, an approach that emerged in the 1990s to help patients create new nerve sensations for their amputated limbs using mirrors to make it appear to them that they were moving both limbs when they moved their remaining limb.

The mirror therapy didn’t work for Johanson. And it can't work for double amputees.

In recent years, researchers have looked to computers to build on the ideas first introduced by mirror therapy. Virtual reality allowed doctors to move beyond the limitations of carefully aligned mirror boxes. Still, the therapy relied entirely on visual suggestion.

Max Ortiz Catalan and others from Sweden's Chalmers University of Technology took an additional step with Johanson and created an augmented reality system in which myoelectric electrodes on his stump indicated his attempted muscle movements for the missing arm, and an arm image on screen reflected those movements back to him. If he moved his torso, the virtual arm moved with him on the screen.

Johanson was asked to perform particular movements with the phantom limb. He even drove a racecar by moving the muscles at the end of his existing arm to show intent of moving his missing hand.

"Our method differs from previous treatment because the control signals are retrieved from the arm stump, and thus the affected arm is in charge," said Ortiz Catalan.

Be Part of the Future

Sign up to receive top stories about groundbreaking technologies and visionary thinkers from SingularityHub.

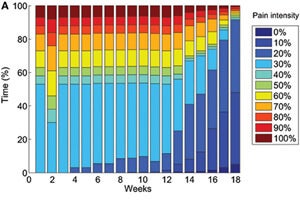

Over 18 weeks, the patient reported longer periods with no pain and shorter periods of intense pain (figure). Johanson said that the default position of his phantom hand relaxed from a tight fist to a half-open position, the neutral position shown by the virtual hand.

It goes without saying that such results will have to be repeated with more patients, but the work offers an example of innovative medical applications for augmented reality.

The same myoelectric signals that controlled the AR hand in the Swedish study have also been used to control prosthetic hands, such as the BeBionic. At least one study suggests that this type of prosthesis can ease phantom limb pain, according to Ortiz Catalan.

But Johanson wears a body-controlled prosthetic hand, in which muscles are somewhat arbitrarily assigned to control limited movements of the device. Simply seeing the prosthesis move did not relieve the pain, while controlling the AR hand with more natural muscle movements did.

It will be interesting to see how prosthetics controlled by neural impulses affect phantom limb pain as they become commercially available. Recently a prosthetic hand that sends sensation back to the brain was studied on a human patient. Although phantom limb pain isn’t well understood, many believe that it stems from neurons in the brain that were once assigned to the amputated limb falling into disuse. If the neural impulses from a prosthesis in fact draw on the same brain resources that once controlled the patient’s natural limb, it’s theoretically possible that they could relieve phantom limb pain.

"This is very likely," Ortiz Catalan told Singularity Hub. But "there is no data on that because there is no prosthesis today controlled by nerve impulses, at least not outside short experiments within the laboratory environment."

Images courtesy Max Ortiz Catalan & Frontiers in Neuroscience

Cameron received degrees in Comparative Literature from Princeton and Cornell universities. He has worked at Mother Jones, SFGate and IDG News Service and been published in California Lawyer and SF Weekly. He lives, predictably, in SF.

Related Articles

This Light-Powered AI Chip Is 100x Faster Than a Top Nvidia GPU

How Scientists Are Growing Computers From Human Brain Cells—and Why They Want to Keep Doing It

These Brain Implants Are Smaller Than Cells and Can Be Injected Into Veins

What we’re reading