How to 3D Print Instant Disaster Relief

Share

For the first time, late last year, astronauts 3D printed tools and replacement parts in space. It was a momentous occasion. Astronauts are at the mercy of resupply missions, and it can take weeks or even months for needed items to reach the space station.

3D printing, however, empowers astronauts to manufacture what they need onsite—and that power has revolutionary implications for space exploration in earth orbit and beyond.

But astronauts aren’t the only humans with a supply problem.

In the aftermath of a natural disaster or war, affected areas may as well be on the moon. And instead of a few astronauts making do without a broken spanner, tens of thousands must do without critical items, like medical supplies, as the outside world mobilizes.

Just as 3D printing promises to revolutionize space travel, it might be equally, if not more, significant back here on earth. But first a little background on the challenge we face.

Humanitarian supply chains are long, complicated and problem ridden.

At each step in the chain, agents, middlemen, functionaries and bureaucrats push and pull goods and services—all for a price. This standard supply chain has heavy lead times, requires good information systems, well-trained staff and should be attuned to the customer’s needs (disaster affected people and aid workers alike).

To date, the focus has been on stockpiling, distribution of cash and improving basic efficiencies, but there has been little done to transform the situation. And so it calls for disruption. Instead of relying solely on the supply chain—what if we could make much of what was needed onsite (or at least nearby)? If we can do it in space, we can do it here too.

My organization, Field Ready, for example, combines 3D printing with low-tech innovation such as “hyper-local” manufacturing to increase the independence of aid workers and those affected by disasters. And we tested out our approach in Haiti at the end of last year.

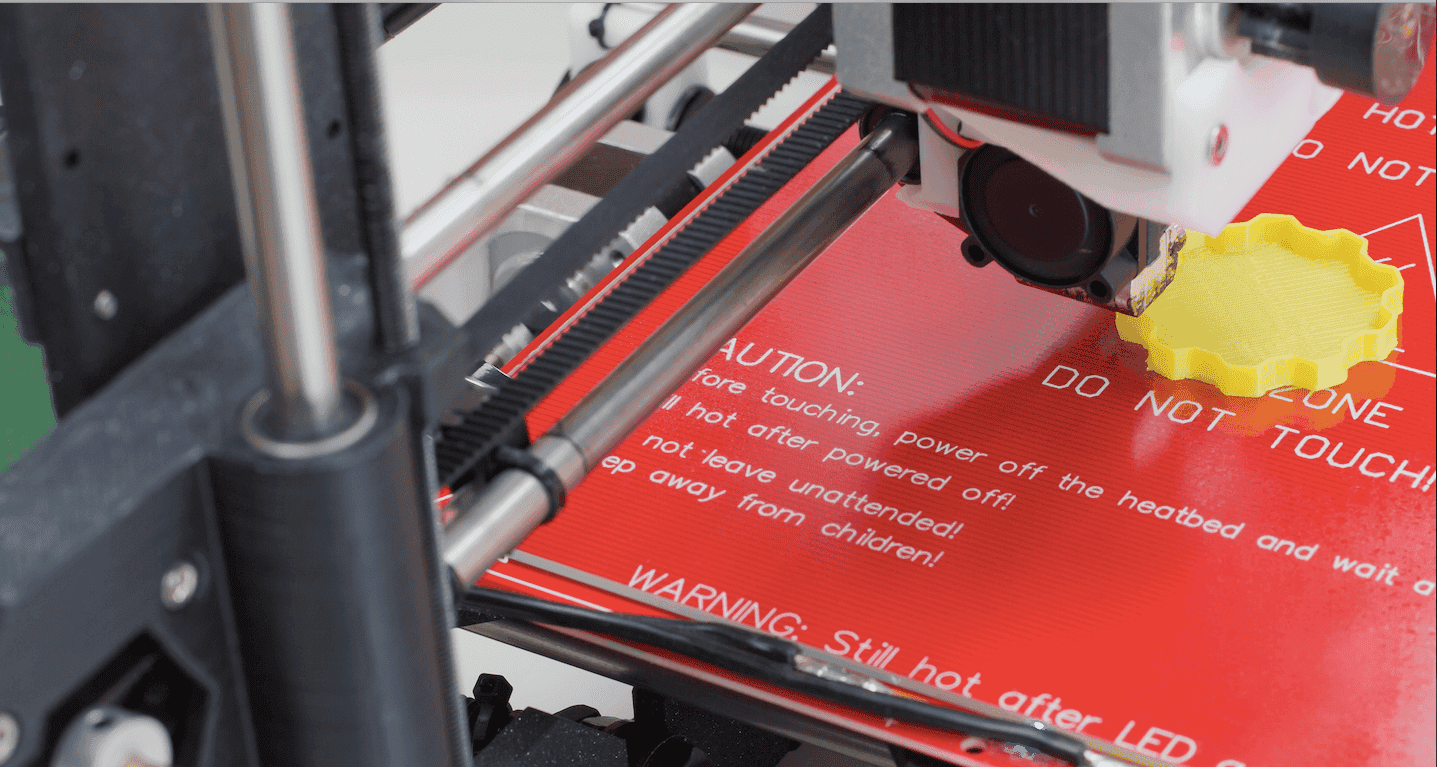

To start, we talked to health practitioners to better understand their challenges and design possible solutions. Then using 3D printers—UP Mini and MakerBot Replicators—and a range of software, we made and tested a series of medical disposables and other printed items. Of the 165 prints, including prototypes, 110 items were distributed for local use.

We also printed a unique prototype prosthetic hand (using just five parts), filament guides that were used to repair and improve the printers, a butterfly-needle holder, a prototype screwdriver, prototype pipe clamps and bottles and a mock-up of a gas cylinder regulator.

Traditionally, items like these would take several weeks and often months to make their way to a disaster zone—but with a few 3D printers and spools of filament, delivery is near-instantaneous.

The potential good here is enormous, and we aren’t the only ones developing a solution.

Others include Oxfam (with their partners Griffith University and MyMiniFactory.com) in Kenya and the Innovation & Planning Agency (IPA) in Jordan. Another group, eNable, is working to print prosthetic limbs using an all-volunteer-based approach.

At the same time, a step beyond 3D printing is already underway.

Be Part of the Future

Sign up to receive top stories about groundbreaking technologies and visionary thinkers from SingularityHub.

MIT’s Self-Assembly Lab is pioneering 4D printing, which allows materials to “self-assemble” into 3D structures. For humanitarian aid, this may mean small bridges, structures for medical care and water piping can be quickly deployed following a disaster. It may also allow items to repair themselves when after-shocks and other hazards re-occur.

And it isn’t just about the tech. The Ethical Filament Foundation, for example, promotes filament sourced directly from waste picker groups in developing countries, thus creating income generation opportunities and at the same time supplying 3D printers.

All this points to future relief efforts broadly transformed by technology—and such a future can’t come fast enough.

Humanitarian relief is still messy, tough and perplexing. With few exceptions, aid is provided in the most difficult places on earth, and relief situations are the outcomes of catastrophic failure—usually, a collapse of cooperation and good governance.

In 2013, there were 334 “country-level natural disasters” in 109 countries. Wars in Syria and Ukraine, as well as festering often-forgotten conflicts in places like Nigeria, Yemen and Afghanistan, continue to wreak havoc. Meanwhile, the growing challenges of urbanization and climate change are having an uncertain impact.

Technology can be a powerful force for good, but due to the necessarily improvisational and urgent nature of relief work, the adoption of technology and innovation has been slow. That’s changing. In the last several years, there has been an increasingly active push to bring about change based on innovation, technology and new ways of thinking.

Examples beyond 3D printing include biometric scanners to replace lost documentation and prove people’s identity, UAVs for restoring communications and delivering critical relief items, wearable devices to aid search and rescue and reconnect families and networked sensors for detecting and reporting fires in informal human settlements.

Last August, Jason Dorrier wrote a thoughtful post entitled “We Justify Human Suffering Because We’ve Never Had a Choice in the Matter,” which points toward a shift in the way people are thinking about disasters. Rather than hapless victims, we now have in our grasp new ways of tackling humanitarian challenges head-on.

Eric James is co-founder and director of Field Ready, a 2012 GSP Teaching Fellow and visiting lecturer at Singularity University, and has spent over 15 years working as a humanitarian aid worker.

Images courtesy Shutterstock and Field Ready.

Eric James, PhD is an entrepreneur, aid worker, author and lecturer specializing in the management of humanitarian relief and disaster response. Eric began his career in international development with USAID in 1995 and has since worked for a number of NGOs including IMC, IRC, RI and ChildFund as well as the UN. This professional experience spans over twenty countries including Afghanistan, Albania, Burundi, East Timor, Iraq, Liberia, Sri Lanka and Zimbabwe. His research interests include improving humanitarian assistance, NGO management and civil-military relations. He taught previously at the University of Manchester's Institute of Development Policy and Management, DePaul University's School for Public Service and is a Lecturer at University of Minnesota's Humphrey School of Public Affairs. In addition to academic articles, he is the author of Managing Humanitarian Relief: An Operational Guide for NGOs (Practical Action 2008).

Related Articles

AI Companies Are Betting Billions on AI Scaling Laws. Will Their Wager Pay Off?

Super Precise 3D Printer Uses a Mosquito’s Needle-Like Mouth as a Nozzle

Is the AI Bubble About to Burst? What to Watch for as the Markets Wobble

What we’re reading