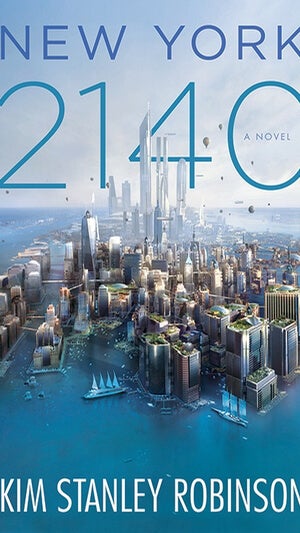

‘New York 2140’ Is a Sci-Fi Vision of the World Reshaped by Climate Change

Share

If a trip to Venice is your ideal holiday, then you’re going to love the future.

Most of us, however, will be quite sobered by Kim Stanley Robinson’s upcoming novel, New York 2140, a near-future projection of a world reshaped by climate change. Sea level has risen by 50 feet, flooding the Big Apple and countless coastal cities around the planet. Thousands of species have gone extinct.

The same economic and political forces driving the world ever closer to that reality are still in charge, setting life on a perpetual spin cycle of boom and bust, with the rich always getting richer.

Robinson’s latest science fiction creation is definitely no beach read. Of course, most of those beaches will be wiped out as the ice sheets in Antarctica and Greenland melt in the coming centuries. Most scientists agree that several meters of sea-level rise are likely inevitable in the next hundred years, though Robinson’s scenario is definitely at the extreme end of predictions for the mid-22nd century.

“I squeezed the timeline a little because I also wanted to talk about things happening right now, in global finance and our political economy more generally, so the closer to the present I set the novel, the more it suited my purposes,” he says by email in an interview with Singularity Hub.

"We live in a present mixed with various futures overshadowing us. In essence, we live in a science fiction novel we all write together."

“Near-future science fiction is always making these enjambments of present and future; it’s not unusual in them to smoosh different temporalities together and present them as one moment,” he adds. “Reality seems to do this, too—we live in a present mixed with various futures overshadowing us. In essence, we live in a science fiction novel we all write together, as I’ve been saying for some time. This book is another example of that, and writing it felt like writing realism. There’ll be many a supposedly realist novel published in 2017 that isn’t as realistic as this one.”

Realism is a trademark of Robinson’s science fiction, and his latest book is no exception. He seems particularly familiar with the scientific literature on climate change, especially as it relates to the pending collapse of parts of the world’s major ice sheets.

Return to the Ice

This isn’t all that surprising, really: about 20 years ago, Robinson visited Antarctica as part of the National Science Foundation’s Artists and Writers Program. The result was his novel Antarctica, which was quite prophetic in some of its predictions when it was published in 1997.

Robinson returned to the (still mostly) frozen continent in 2016, partly at the behest of the NSF. The $7-billion federal agency is planning to rebuild its main research base, McMurdo Station, over the next couple of decades and informally sought Robinson’s advice on its long-range plans.

Kim Stanley Robinson

The visit also included a rare nonfiction writing project for Smithsonian magazine about The Worst Journey in the World, Apsley Cherry-Garrard’s memoir about Robert Falcon Scott’s 1910–1913 British Antarctic expedition.

Robinson found on that return trip to the Ice—as those who journey there regularly refer to it—that at least one of his own predictions about how people respond to living in such an extreme environment wasn’t entirely on target.

“The main thing that struck me this time was that I had thought that Antarctica wrecked the lives of the people who fell in love with it, by distorting their careers and making their life back north so peculiar,” he says. “That turns out not to be entirely true. I saw a lot of people there whom I’d met in 1995, and from them I got the impression that although it takes some effort, one can construct a lifelong Antarctic career that is sane and satisfying. That was a pleasure to learn.”

Back to the future

In one of the more insane moments of his forthcoming novel, a half dozen polar bears suddenly escape into the cabin of character Amelia Black’s airship the Assisted Migration. She had been transporting the animals—on the brink of extinction—from the Arctic to Antarctic, a colder climate where they might be able to recover their population on a diet of seals and penguins.

"[T]here’s no such thing as pristine wilderness anymore."

After some harrowing aeronautical maneuvers by the autopilot, Frans, the powerful predators are recaptured and eventually set free in Antarctica—only to be killed (nuked!) by eco-terrorists bent on keeping the frozen continent pristine.

A 22nd-century version of a reality TV star, Amelia bristles at the idea of purity in a world that has been reshaped by millennia of human engineering. It’s a sentiment shared by Robinson.

“[T]here’s no such thing as pristine wilderness anymore, because the atmosphere is a part of it, and we’ve changed that chemically. Same with the oceans.

“So I think the overriding consideration now is for us to work to avoid extinctions as much as possible, and save as many species as we can by way of active ecological interventions of all kinds. In that effort some wilderness is good, yes, but also interventions that are part of making working landscapes of various kinds, including some unconventional mixes and movements, essentially whatever it takes to keep species alive.”

Clean technology unleashed

The human species, despite the devastation wrought by an unpredictable climate, is far from becoming extinct in fictitious 2140. Technology has proven to be a valuable tool for survival, but exists largely in the background of the novel.

Be Part of the Future

Sign up to receive top stories about groundbreaking technologies and visionary thinkers from SingularityHub.

After becoming neck deep (times a hundred), people finally concede that pumping carbon dioxide willy-nilly into the atmosphere is the road to ruin. Carbon neutral and even carbon negative technologies rapidly replace dirty energy, construction and manufacturing in Robinson’s partly drowned world.

Photovoltaic paint covers New York’s skyscrapers. Construction materials are made by pulling carbon out of the air and turning it into graphene, which is then transformed into super-strong composites by 3D printing. Electric cars, bicycles and trains come to dominate land transportation, with many roads ripped out to create habitat corridors to help species survive.

"Optimism is a political position, to be wielded like a club... It’s a choice made to insist that things could be better if we worked at it."

Skyvillages serve as the new farms, floating above the Earth, returning only long enough to plant and harvest crops. Livestock becomes free range, though most meat is grown in vats. The urban landscape is also re-envisioned, as Robinson writes, “… farms on the roofs, water capture systems, water tanks on the roofs in the traditional NYC style, lifestraw purification filters, all standard operating procedure everywhere in lower Manhattan.”

He notes for the interview, “Technology is advancing rapidly on these fronts, if you use the usual sense of the word and mean machinery and chemistry and materials science. I didn’t make any of that up in this book—maybe the diamond spray [for waterproofing]. But in the important areas, carbon neutral and even carbon negative technologies are ready to accomplish what we want to get done—generate energy, grow food, and move around—and they’re being made stronger every year.

“But still they can’t save us, because they are prototypes. There’s been good progress with solar and wind power, and in other areas, but they all have yet to be implemented at speed, they are still constrained by what gets called market forces. They have to be paid for—the materials and the human labor time it will take to implement them.

But if we continue to believe what our current economic system tells us, we can’t afford to do that. We can’t afford to save the biosphere and create a sustainable civilization—it’s too expensive! Economics proves it, and is the law of the world.

So what does that mean? It means that our economics is inadequate to the situation we find ourselves in. It’s a fraud on the future generations, a Ponzi scheme, a mistake we’re trapped in—however you want to characterize it, it isn’t up to the task of rapidly implementing our already-invented clean techs.”

Economics restrained

Unfettered capitalism and the practices that led to the 2008 economic meltdown are squarely in Robinson’s crosshairs in New York 2140, where the future is no less unscrupulous than the present. The subprime mortgage crisis has been replaced by something he calls the Intertidal Property Pricing Index, where investors hedge against properties that exist in the fragile zone between high and low tide—another riff on sell high and buy low.

In the end, Robinson’s unlikely cast of characters overcome market forces and cash in on a better society. In light of recent rising uncertainty in the United States and abroad, I couldn’t help but ask Robinson if he’s still optimistic.

His answer:

“Optimism is a political position, to be wielded like a club. It’s not naïve and it’s not innocent. … [O]ptimism is a moral and political position. It’s a choice made to insist that things could be better if we worked at it. [Italian neo-Marxist theorist Antonio] Gramsci suggested this with his motto, ‘Pessimism of the intellect, optimism of the will.’

“This is just one moment in a long battle between science and capitalism. That’s the story of our time, and the story won’t end in our lifetime, but we can pitch in and make a contribution toward the good, and I trust many people will. Is that optimism? I think it’s just a description of the project at hand.”

Image Credit: Shutterstock

We are a participant in the Amazon Services LLC Associates Program, an affiliate advertising program designed to provide a means for us to earn fees by linking to Amazon.com and affiliated sites.

Formerly the world’s only full-time journalist covering research in Antarctica, Peter became a freelance writer and digital nomad in 2015. Peter’s focus for the last decade has been on science journalism, but his interests and expertise include travel, outdoors, cycling, and Epicureanism (food and beer). Follow him at @poliepete.

Related Articles

Data Centers in Space: Will 2027 Really Be the Year AI Goes to Orbit?

How Scientists Are Growing Computers From Human Brain Cells—and Why They Want to Keep Doing It

Scientists Say We Need a Circular Space Economy to Avoid Trashing Orbit

What we’re reading