Designer Babies Dilemma in Sharp Focus With Fast Moving Fertility Tech

Share

Moral panic around “designer babies” is nothing new, but rapid advances in technology that allows adult cells to be reprogrammed into sperm and egg cells could bring the issue into sharp focus.

Since the 90s it has been common practice to genetically profile embryos used in in vitro fertilization (IVF) treatment. This is done largely to screen for genetic diseases, but many genes that contribute to traits like eye color, height or athleticism are well-known.

At present their impact can’t be predicted with much certainty, but it’s not inconceivable that the same process could be used to select for these characteristics. That’s why most countries restrict embryo screening to medical uses or outright ban it, though the US is notable for having no federal regulation governing the process.

Despite this, the expense and complexity of producing embryos for IVF make designing the perfect baby largely impractical. The main limitation is the fact that eggs need to be drug-induced and surgically harvested in very small numbers, seriously limiting the number of embryos a couple has to choose from.

However, an emerging technology called in vitro gametogenesis (IVG) could provide a way to create large numbers of both eggs and sperm in the lab, which the authors of an editorial in the journal Science Translational Medicine last week say could have serious scientific, ethical and legal ramifications.

"IVG may raise the specter of 'embryo farming' on a scale currently unimagined, which might exacerbate concerns about the devaluation of human life," wrote Harvard Law School Professor I. Glenn Cohen, Dean of Harvard Medical School George Daley and professor of medical science at Brown University Eli Adashi.

"IVG could, depending on its ultimate financial cost, greatly increase the number of embryos from which to select, thus exacerbating concerns about parents selecting for their 'ideal' future child."

The method allows scientists to create gametes—sperm and eggs—from stem cells. These stem cells can come from embryos, but it is also possible to reprogram adult cells into so-called induced pluripotent stem cells.

Last October, Japanese researchers used IVG to develop viable egg cells in mice, but the approach is still experimental, and it will take considerable research to translate the technology into humans. The authors say clinical applications are unlikely in the near term and the main contribution will be a better understanding of reproductive science.

But at the same time, the authors note that the breakneck speed of scientific progress means these developments may happen sooner rather than later, and the dramatic implications of the technology mean it would be wise for scientists and legislators to get out ahead of the issues.

“IVG has the potential to upend one of the most traditional elements of human culture—our understanding of what parenthood is and how it occurs,” said Cohen, in a Harvard press release. “It is critical for law and medical ethics to grapple with the far-ranging implications of this new technology.”

Be Part of the Future

Sign up to receive top stories about groundbreaking technologies and visionary thinkers from SingularityHub.

The implications aren’t all negative—the technology has the potential to revolutionize the treatment of infertility by offering a safer, less invasive alternative to traditional IVF that could potentially have far higher success rates. It could also help reduce the risks of devastating mitochondrial disease and provide an inexhaustible supply of lab-made embryonic stem cells, which could dramatically accelerate medical research.

But at the same time, the technology is likely to amplify ethical concerns about the use of human embryos in research due to the scale of production it would enable. The ability to derive gametes from adult cells even raises the prospect of people's genetic code being stolen and them being made unwitting parents without their consent.

The headline concern, though, is making it much easier for people to create scores of embryos and then select the "best" for IVF. Combined with technologies like CRISPR/Cas9, which allows high-precision editing of the genome, it could even be possible to edit traits as well as just select for them.

The fear is that this could effectively usher in the kind of eugenics critiqued in the movie Gattaca, where economic inequalities begin to translate into genetic inequalities as those who can afford it pay to give their children the best start in life.

At the same time, others have warned against regulatory overreaction that could throw the genetically modified baby out with the bathwater. “A fear of designer babies should not distract us from the goal of healthy babies,” University of Oxford bioethicist Christopher Gyngell writes in The Guardian.

While these issues may not become a reality for decades, it would be wise to start thinking now about how to tread the fine line between creating a genetic underclass and stifling medical innovation. As the authors write in conclusion, “Before the inevitable, society will be well advised to strike and maintain a vigorous public conversation on the ethical challenges of IVG.”

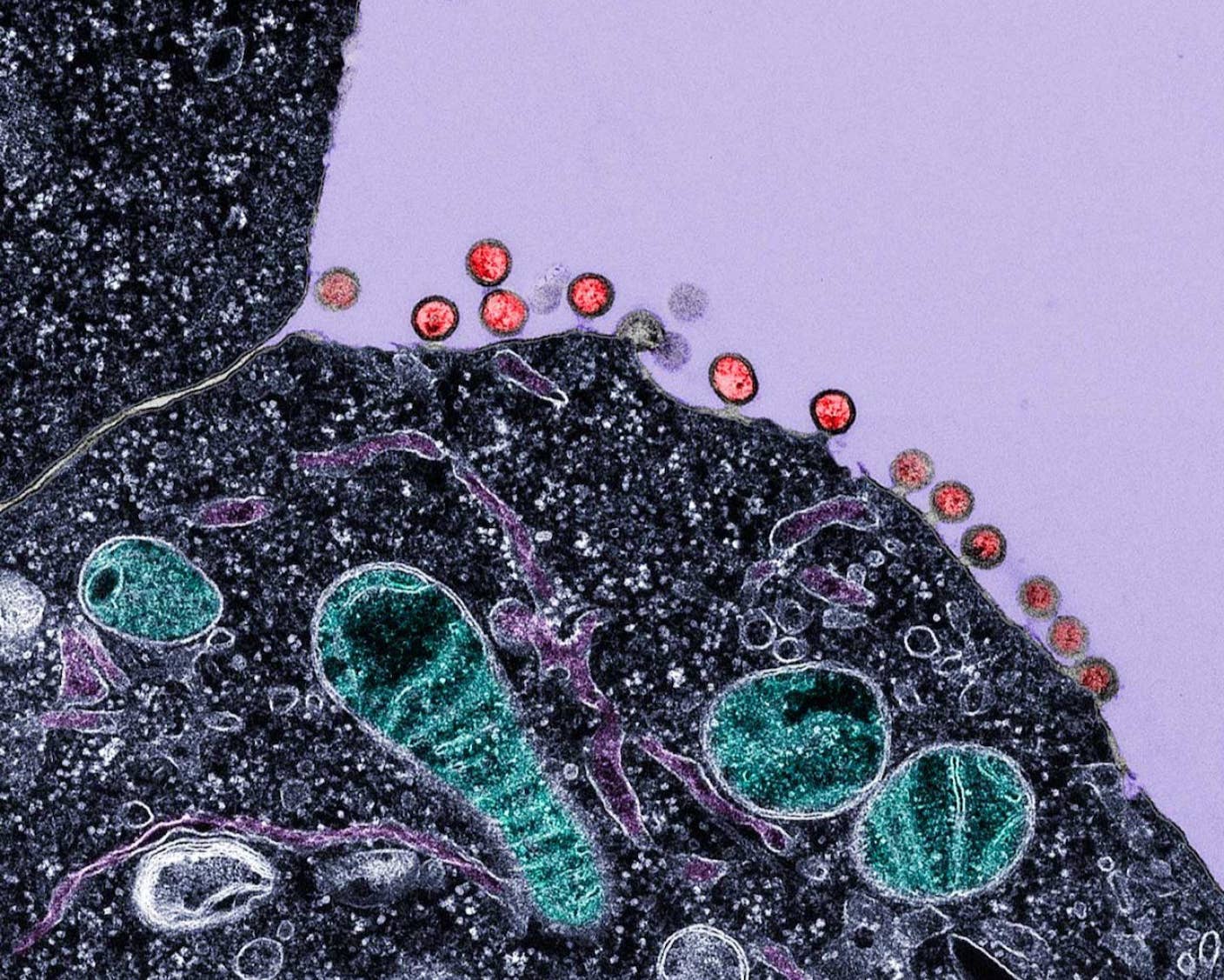

Image Credit: Shutterstock

Related Articles

This Week’s Awesome Tech Stories From Around the Web (Through December 13)

New Immune Treatment May Suppress HIV—No Daily Pills Required

How Scientists Are Growing Computers From Human Brain Cells—and Why They Want to Keep Doing It

What we’re reading