Piloting your drone aircraft through an intricate, Star Wars-like obstacle course or ramming an enemy to the ground in a dogfight—sounds slightly like science fiction, doesn’t it? It’s not. In fact, both sports already exist.

They are part of the rapidly expanding ecosystem of drone sports, which looks set to follow the growth trajectory of the hugely popular world of live video gaming known as eSports.

Something that owes a lot to the speed of technological development and a punk-meets-maker-movement attitude. It’s a melding that has already led to experiments with paintball gun dogfights—and in one case, a flying flamethrower.

Taking the pilot’s view

You have probably already heard about drone racing, which illustrates how quickly drone sports have taken off.

Drone Racing League (DRL) is a good example. DRL organizes drone races across the globe and films them using a mix of camera drones, stationary cameras and first-person-view (FPV) video. Since its launch in 2015–2016, its races have been viewed on YouTube, Twitch and Facebook over 43 million times. DRL events have also been on TV, and the organization expects the coming season to be viewable on TV screens in up to 75 countries.

“Part of the fascination is seeing drones whiz around at 80 miles an hour,” Nicholas Horbaczewski, CEO and founder of Drone Racing League, says.

Spectators at live events also have the opportunity to see exactly what the pilots are seeing.

Each drone is equipped with a camera that streams images in real time to first person view (FPV) goggles worn by the pilots. The pilot literally feels like he or she is sitting on the nose of the drone, as it flies around courses in venues like outdoor stadiums, factory buildings or tents.

“Drone racing essentially means that a pilot can shift their consciousness into the aircraft, flying through tiny gaps without any fear of physical danger,” Chris Ballard, director of communication at Freedom Class drones, explains.

Anyone wearing FPV goggles can share the pilot’s experience, something that has often been compared to Star Wars or a computer game.

The early golden years

DRL is just one of the drone racing organizers around today.

Freedom Class is an Australian group that is taking drone racing in a slightly different direction.

If Webster’s dictionary needs a definition for “big-ass racing drone,” they could use a picture of the 1.2 meter Freedom Class V1.0, capable of speeds up to 160 kilometers an hour. The size solves one of the challenges of live drone races—the fact that following the action and finding out who is actually in the lead can be difficult when the competing craft are roughly the size of a shoebox.

Then there’s DR1 Racing, whose races air on TV channels like Eurosport and Discovery Channel, and MultiGP, which is likely the biggest drone racing organizer based on number of registered pilots (16,195) and chapters (1,041) around the world.

Finding analyses of the market potential of these—and many other—organizers, not to mention drone sports generally, is difficult. However, if the broad market for drones is anything to go by, the outlook is promising. A 2016 report from PricewaterhouseCoopers forecast that the world drone market will be worth nearly $127 billion by 2020.

The price of drones and other technology is also falling rapidly. A racing drone, FPV goggles and controller would likely cost you $500 to $800 today. However, entry-level equipment packages are available for around $200–$300. Some industry insiders expect that to fall to around $100 within a couple of years. Many organizers actively encourage entry-level drones as a starting point because part of the learning process of drone racing invariably involves crashing—at speed.

The final indicator comes from drone sports’ closest cousin, eSports. Both are children of the 21st century, taking advantage of falling prices of technology. Both also excel at using “new media” channels like YouTube, Twitch, Twitter and Facebook to reach and engage with their audiences.

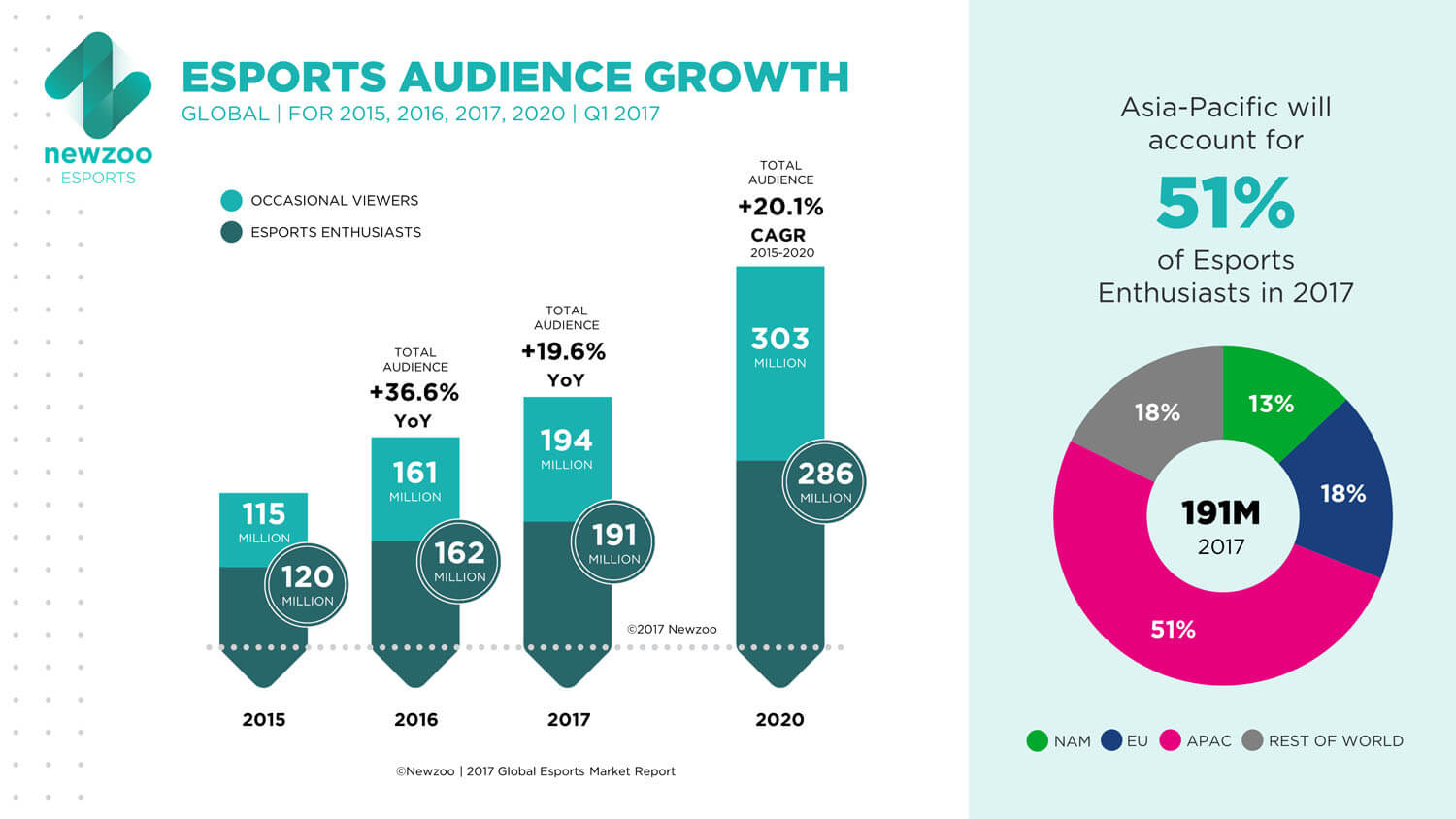

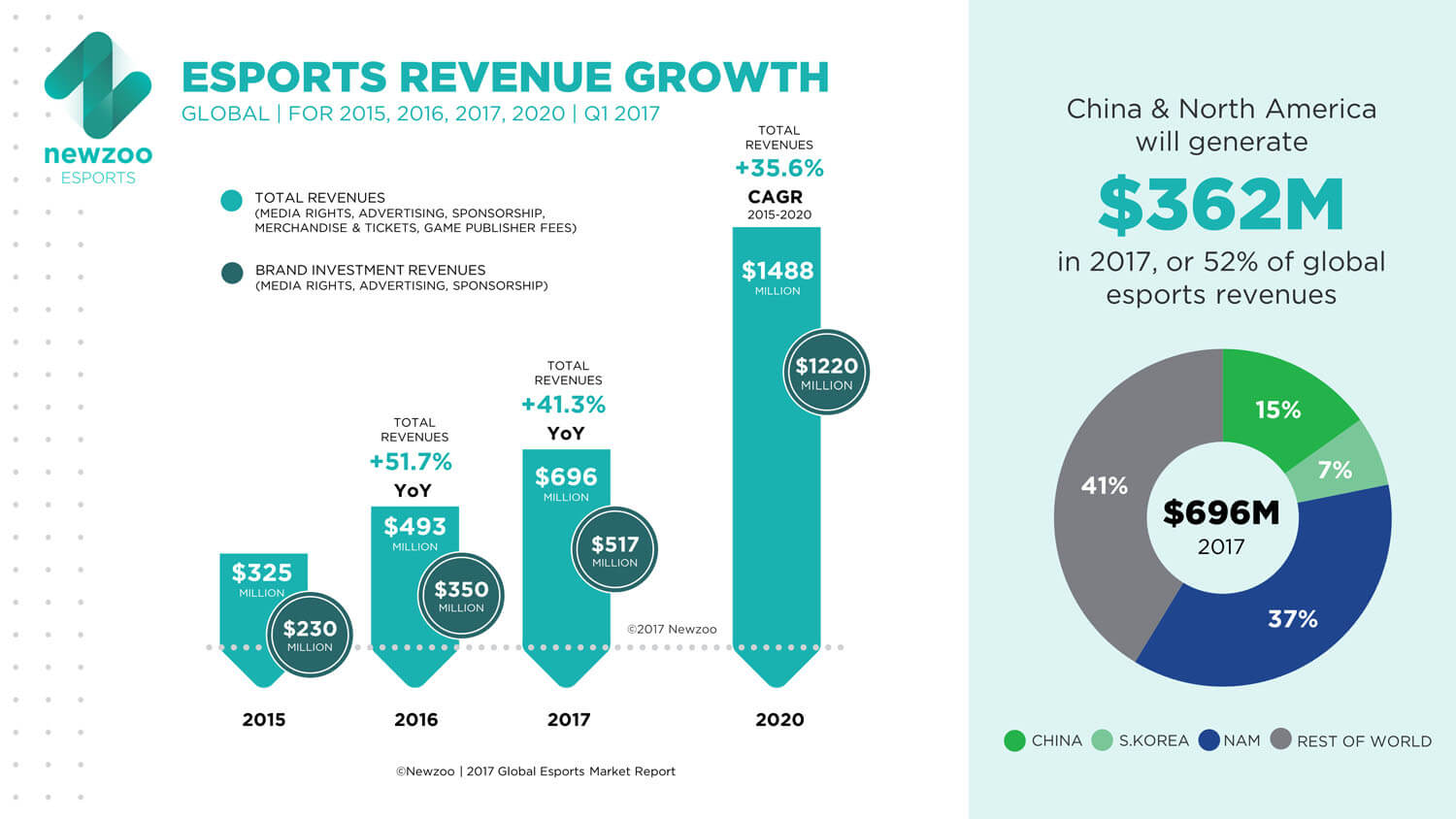

Newzoo, an eSports analysis company, has projected the growth of both global audience and revenue in eSports, and given the similarities to drone sports, it may provide a useful benchmark for growth potential.

Source: Newzoo

Endless possibilities

Drone racing is far from the only kind of drone sport. One other example traces its roots to the area around San Francisco.

“In the beginning, back around 2011–2012, it was a bunch of geeky maker-friends who met up on Friday nights in someone’s garage to fly drones and smash them in battles,” Marque Cornblatt explains.

The concept grew, and some drone pilots quickly started adding things like net-launchers, bottle rockets and paintball guns to the drones. One ambitious maker even attached a mini-flamethrower. From five to six people meeting up in a garage, the events quickly grew to 150–200 people.

Cornblatt and his compatriots decided to form the Aerial Sports League (ASL), which today hosts a range of different drone sports events, including one that is perhaps best likened to a UFC of drone combat with added pit crews. Drone pilots attempt to destroy or force opponent’s drones to the ground. If a drone is downed, its crew has a limited time to get it back in the air. The loser is the drone that’s literally unable to fly anymore.

ASL has strong ties with the maker movement. Its installation and competitions have proven to be the single most popular exhibition at several recent Maker Faires across the US, with over 250,000 spectators in 2016.

The potential for further inventions and iterations of drone sports is part of what gets Marque Cornblatt most excited about where drone sports are today.

“Adding laser tag and paintball markers to drones would make actual dogfights a possibility. Our drone battles could expand into multiplayer king-of-the-hill kind of events,” he says.

The same goes for the technologies used to make and fly drones. Cornblatt explains he is currently working on a system that lets you fly the drone using things like eye movement and head-tracking.

Tech opening the doors wide

Much of the innovation is ground-up, coming from the grass roots of the fledgling sport, where many—if not all—pilots and drone league organizers have learned how to repair and upgrade drones out of sheer necessity.

“The technologies are evolving at an incredible rate, with new products and features seemingly coming out on a monthly basis. This is being driven by the DIY aspect of the drone community,” Dave Heavyside, creative director at Freedom Class Drones, says.

One example is the ‘Tiny Whoop’ phenomenon. Team Big Whoop pilot Jesse Perkins decided to modify a standard Blade Inductrix microdrone by adding a micro-FPV camera and upgrading the motors and battery from different suppliers. The recipe proved so successful that people started ordering the upgrades from Jesse’s website. Today, the term Tiny Whoop is more or less synonymous with micro / indoor FPV drones.

This link to the maker/hacker movement will stand drone sports in good stead, as they still face technical challenges, including how to improve the quality of FPV-view and broadcast it beyond the physical location. Once that happens, you should be able to follow a drone race with FPV goggles at home in your living room. AR/VR technology is another area that drone sports have yet to fully integrate and exploit.

Drone sports could soon be getting help with these issues from the next generation of STEM-interested innovators, who are learning through drones.

“We get emails from high school teachers about how drones are helping them reach the students and from high school students saying thanks for getting them interested in science. Once kids / students get to work figuring out how drones work and how you can improve them, they don’t even realize that they’re learning things like mechanical engineering, electronics and aerodynamics,” Nicholas Horbaczewski says.

Banner Image Credit: DRL