The Power of Unsafe Thinking to Bring Bold, World-Changing Ideas to Life

Share

Jonah Sachs is a storyteller, entrepreneur, and “unsafe thinker.”

Sachs is the founder and former CEO of Free Range studios, a pioneering creative firm that helped create some of the first viral marketing campaigns around social issues, such as the “The Story of Stuff,” which was viewed by over 60 million people and whose purpose was to educate and engage people about the environmental and social impact of consumer goods.

Working on global campaigns from Greenpeace, Human Rights Campaign, and the ACLU, among corporate clients, Sachs has helped pioneer innovative approaches to digital media to bring new social values such as equity, empowerment, and responsibility to the forefront of business and popular culture.

Sachs’ newest book, Unsafe Thinking: How to Be Nimble and Bold When You Need It Most, blends decades of research on creativity and performance with stories of trailblazers in business, health, education, and activism and provides practical tips for how we can all get more comfortable bringing bold, world-changing ideas to life.

Lisa Kay Solomon: What does it mean to support “unsafe thinking”? Why is it so important at this moment in time?

Jonah Sachs: Unsafe thinking is the term I use to describe the ways innovators break out of standard operating procedure, break old habits of problem solving, and go against dead conventional wisdom when they need it most. We live at a time of extremely rapid change, and that means we too are constantly challenged to change. But that’s really hard for human beings, and it often gets harder once we’ve reached a reasonable level of success.

If we want to tackle the enormous business, social, political, and environmental problems we face, safe thinking and incremental solutions simply won’t work. I believe that practices of unsafe thinking can help us accelerate intelligent risk-taking and empower innovators to be more creative and to act more boldly.

LKS: A lot of the stories you share in the book mention leaders who had to learn how to get comfortable with being uncomfortable. Can you share some tips on how more leaders can embrace that practice in their everyday work?

JS: I was initially surprised by what I heard from innovators. I had expected many of them to just be naturally drawn to risk, to be the “crazy ones,” as the old Apple ad called them. But each of them told me how much fear they’ve faced throughout their careers. What made them different than average performers wasn’t that they didn’t feel anxiety. It’s that they learned to reframe it, for themselves and their teams. They consistently told themselves that they’d never had an idea that was breakthrough that didn’t scare them and that didn't bring up many easy objections. So they came to see fear as a sign they were on their creative edge and chose to make a hit of moving toward it rather than away from it.

LKS: You’ve spent a lot of time with leaders who have used meaningful setbacks as fuel for their next ventures. What are some patterns you’ve seen from leaders who are able to recover—and even thrive—after a failure versus those who don’t?

JS: One of my favorite stories was that of Julie Wainwright. When I met Julie, she was running The Real Real, a billion-dollar online consignment business. She was passionate and confident. But Julie is also known in Silicon Valley as one of its biggest failures. She ran Pets.com during the first dot-com bust. She lost her company, her reputation, and her marriage all on the day she had to shut Pets.com down. Julie had this amazing ability to learn from but not dwell on failure. Instead, she used it as one of many experiences that she referenced as she made choices about the future.

Experiences with strong emotional content tends to occupy unreasonable space in our understanding of the world—it’s known as availability bias. When we have a strong negative experience, we tend to walk into every situation and see signs that it’s similar to the one that’s caused us pain. This bias can be extremely distorting because failure is often the result of some combination of the environment we were in, our actions, and luck.

Leaders are best served when they humbly use their failure as only one of many data points they use to evaluate a new situation. Often, focusing on the stories of others instead of being solely focused on their own stories helps introduce these needed new data points. That’s part of the reason I tell a lot of stories in the book about those who bounce back from failures.

LKS: Your work talks about the importance of balancing the “beginner’s mindset” with expertise. Why are both so important for creative thinking and innovation?

JS: The idea of a rank beginner coming into a field, seeing something nobody else does, and shaking it up is a nice one, but it’s a myth. To do anything of value, we need to gain expertise: to know what’s been tried before, to understand the patterns around us, to benefit from the thinking of the masters that came before us. But there’s a point on the graph at which expertise and the potential for innovation part ways. That point is called “entrenchment” and it happens often when our egos get attached to what we know, or what we think we know. Experts who are acknowledged in their fields and who self-identify with their expertise are often threatened by new information that doesn’t fit their models of the world. They don’t look at ideas that contradict theirs with curiosity and openness—the costs seem too high.

Be Part of the Future

Sign up to receive top stories about groundbreaking technologies and visionary thinkers from SingularityHub.

In games with clearly-defined rules that never change, unlimited expertise is great. But in games with sketchy rules that are always changing—and that’s the world we face today—identifying as an expert can be deadly. I found that the best unsafe thinkers identified as explorers. That is, they were passionate about gaining knowledge and understanding their fields. They just never thought of themselves as experts.

LKS: How can leaders build cultures of “unsafe thinkers”? What are some choices they can make to help scale creative, nimble, and bold behaviors?

JS: Ironically, I found that cultures that encourage unsafe thinking worked hard to make people feel safe enough to take big risks. I spoke to Steve Kerr, coach of the Golden State Warriors, a team that has the most creative style of play in NBA history. Steve told me his first work taking over the Warriors involved turning down the pressure and sense that if a player didn’t perform, he’d be kicked off the team. He made the locker room a refuge where everyone felt valued and accepted. So when they got on the court, they were freed from having to look over their shoulders.

Companies can do a number of things to make their teams feel safe enough to get unsafe.

They can celebrate rule-breakers who find important hacks and workarounds instead of forcing these creative rebels to operate in the shadows. They can directly reward not just results and the people who originate great ideas but the people who speak up and challenge consensus or those who take intelligent risks even when those risks fail.

Finally, they need to embrace a wide mix of cognitive types.

Companies that insist on “hiring for cultural fit” too often become monocultures of thought and action. Plenty of research shows that cognitively diverse teams vastly outperform homogeneous teams in situations where creativity is called for. Companies need to work harder to expand the concept of diversity and bring on people with different life experiences and even different value systems. If employees get the message that they must conform to the group and contribute to harmony as a top priority, you’ll get a lot of nice people, but little in the way of breakthrough results.

Image Credit: Roman Tarasevych / Shutterstock.com

We are a participant in the Amazon Services LLC Associates Program, an affiliate advertising program designed to provide a means for us to earn fees by linking to Amazon.com and affiliated sites.

Lisa Kay Solomon is a well-known thought leader in design innovation with a focus on helping leaders learn how to be more creative, flexible and resilient in the face of constant change. Lisa is the Chair of Transformational Practices and Leadership at Singularity University a global community of smart, passionate, action-oriented leaders who want to use exponential technologies to positively impact the world. She coauthored the Wall Street Journal bestseller, Moments of Impact: How to Design Strategic Conversations that Accelerate Change, and more recently, Design a Better Business: New Tools, Skills and Mindset for Strategy and Innovation. Lisa is a frequent keynote speaker on innovation, design thinking and leadership at global conferences and business schools. A passionate educator, Lisa has taught at the revolutionary Design MBA program at California College of the Arts and has developed and led popular classes for Stanford d. School such as Networking By Design and Design With the Brain in Mind. She is also the Executive Producer of the annual Inspired4Schools conference, a design leadership program for educators, and is on the leadership committee for The Nueva School’s Innovative Learning Conference, a biennial gathering for trends related to the future of education.

Related Articles

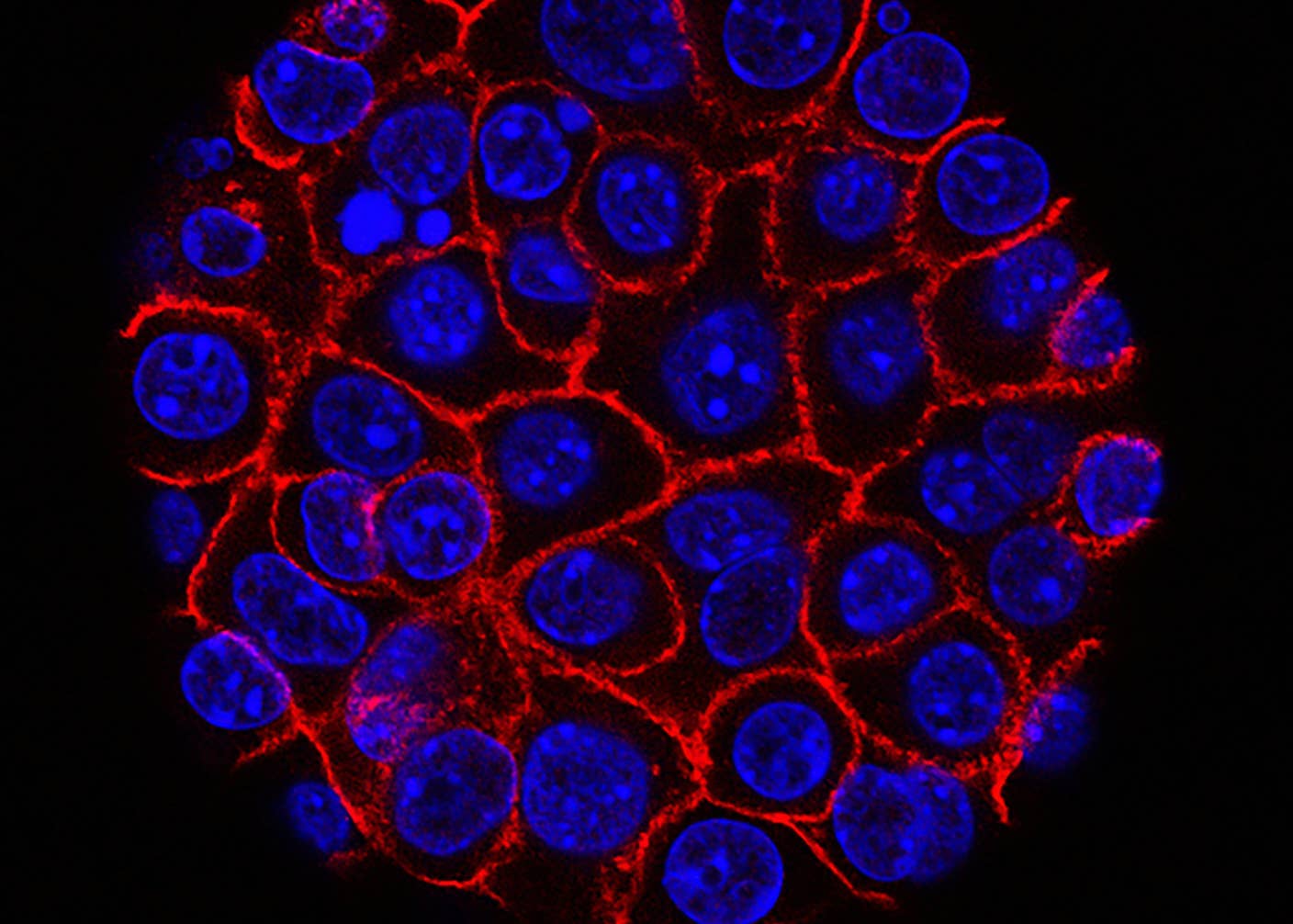

These Supercharged Immune Cells Completely Eliminated Solid Tumors in Mice

New Device Detects Brain Waves in Mini Brains Mimicking Early Human Development

This Week’s Awesome Tech Stories From Around the Web (Through February 28)

What we’re reading