An ambitious plan to build a quantum computer the size of a soccer field could soon become a reality. A startup founded by the researchers behind the idea has just come out of stealth with $4.5 million in funding.

While there has been some headline-grabbing progress in quantum computing in recent years—not least Google’s announcement that it had achieved quantum supremacy— today’s devices are still a long way from being put to practical use.

The reason quantum computers are so promising is their potential to solve problems beyond the reach of even the most powerful supercomputers. While bits in a conventional computer can only adopt the values of 1 or 0, the qubits at the heart of a quantum computer can adopt multiple combinations of 1 or 0 at the same time thanks to the quantum mechanical phenomena of superposition.

Another quantum phenomena called entanglement makes it possible to link many of these qubits together. The combination means that while a conventional computer would have to chug through the numbers sequentially, an ideal quantum computer could sort through every possible combination of 1s or 0s instantly.

Given their complexity, though, this is only useful for problems so big that it would take a conventional computer a very long time to work through. That requires a lot of qubits, far more than anyone has managed to string together so far. The superconducting qubits that industry leaders like Google, IBM, and D-Wave use are also noisy, so it’s expected that we’d need even more qubits to carry out error-correction as well.

The difficulty of scaling up these devices is the reason why people often talk of decades before we see practical uses for quantum computers. But in 2017 researchers from the University of Sussex in the UK put forward a bold plan for a modular quantum computer that could quickly scale up to billions of qubits. And now a startup founded by the same team, called Universal Quantum, has come out of stealth with plans to commercialize the idea.

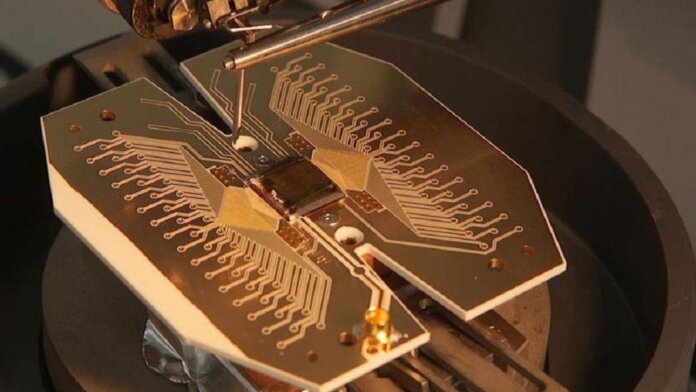

The company is taking a different tack to the market leaders, building its qubits out of trapped ions—charged atoms confined in a particular spot using using electromagnetic fields—rather than the superconducting circuits that have become the most popular solution in recent years.

Trapped ions are promising because they are all identical and therefore don’t suffer from the tiny variations in fabrication that can impact superconducting circuits. It’s also possible to push them into particular states and read those states back out with high fidelity. And most importantly, they are able to maintain their fragile quantum states for much longer than other approaches, which gives them more time to carry out calculations.

But combining large numbers of trapped ions in a single device while still maintaining control of them has proven tricky, and circuits made up of trapped ions are much slower than alternative technologies. Most designs so far also require individual lasers to control each qubit, which quickly gets impractical for devices with thousands if not millions of qubits.

Universal Quantum plans to get round this by using microwaves to control the qubits, relying on the same technology that is found in cell phones. They plan to build modular components of roughly 2,500 qubits which can then be linked together to create larger systems.

A downside to this modular approach is that the links between modules can be far slower than the quantum operations going on inside them, even using optical links that run at the speed of light. The company plans to get around this by instead shuttling the ions themselves around the system.

While they haven’t set any kind of timeline for when they might have a working device up and running, the founders of Universal Quantum told the BBC they are confident the technical capability exists to build the machine. The say the funds they’ve raised so far will be used to find a site and key staff, but that they’ll have to “raise a lot more money” to get the job done.

Betting against some of the largest and most powerful technology companies in the world is certainly a risky strategy. But if this plucky startup can pull off its vision, the quantum age may not be as distant as we think.

Image Credit: Winfried Hensinger