These Mice Were Born From Sperm That Spent Almost 6 Years in Space

Share

As inconceivable as it still sounds, the wheels have been set in motion for humans to one day reach and colonize Mars. There’s already a detailed design for the first Martian city, SpaceX is building its first offshore spaceport to one day launch Starships to Mars (among other missions), and NASA recently flew a helicopter on Mars. But there are a few big pieces of the puzzle still missing, including the answer to one crucial question: after we get humans to Mars, how will we ensure that our species is able to continue there? In other words, we don’t yet know whether humans can reproduce in space.

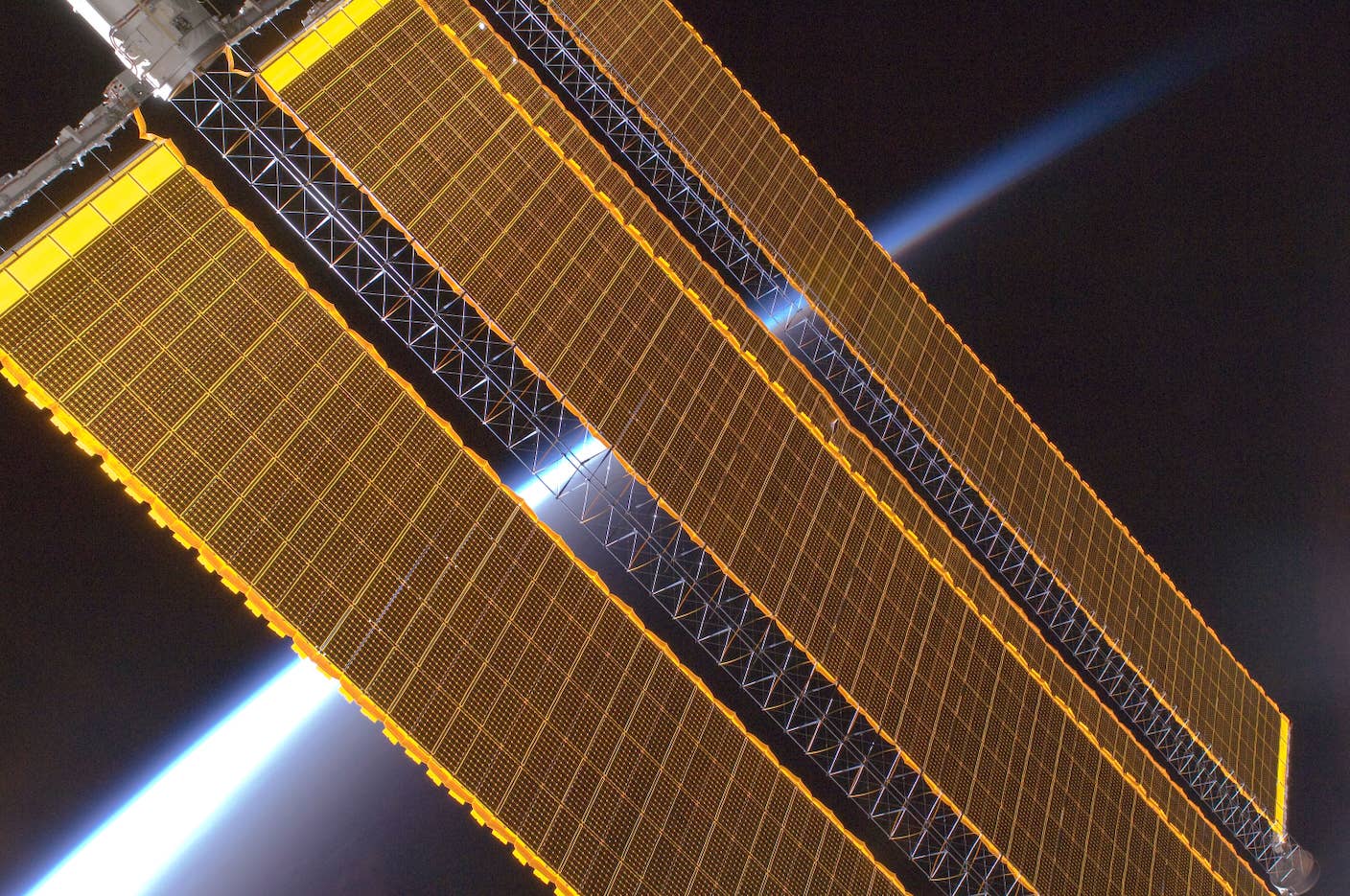

A study by Japanese researchers just brought us a small step closer to answering some of these questions. The scientists sent freeze-dried mouse sperm to the International Space Station (ISS), where it stayed for varying lengths of time—from nine months up to five years and ten months—before being brought back to Earth and used to impregnate female mice. The team published their results last week in the journal Science Advances.

Space Station Sperm

Sending sperm to the ISS seems like a bizarre idea. What could this tell us about humans’ potential to reproduce in space, especially since the sperm essentially took an extended field trip then came back, rather than being turned into babies off-Earth?

The team mainly wanted to study the impact of space radiation on DNA and fertility. Radiation can cause damage to somatic cells as well as germline cells, and in space there’s more potential for harm from solar particle events, where the sun sends out high-charge, high-energy particles. These are called HZE particles, and they’re potent enough to break the interwoven strands of DNA’s double helix. Galactic cosmic rays coming from outside the solar system can cause harm, too.

A species can certainly survive with some genetic mutations, but as more of them accumulate and are passed on to new generations, and the DNA of those generations undergoes additional mutations, it’s not long before you’re dealing with an intractable set of problems—or, as the team put it in their paper, “If radiation were continuously irradiated into the body of a species and several mutations accumulated in germ cells over a long period of time, then the species would become a different species.”

By storing the sperm on the ISS, then, the team was able to observe its behavior and its resilience to space radiation, namely whether its DNA was damaged.

What Happened

Out of 66 male mice, the scientists took sperm samples from the 12 that were healthiest and had the most genetic diversity. They divided the sperm into six different boxes, sending three to space and keeping three on Earth as a control group. The boxes sent to space were brought back nine months later, two years and nine months later, and five years and ten months later, respectively (this final timespan, by the way, is the longest that samples have ever been held on the ISS for biological research).

The team tested the repatriated sperm and the embryos created with them for things like abnormal chromosome segregation, cytoplasmic damage, cell number of blastocysts, and apoptosis rate. They found that the time the sperm spent in space didn’t cause damage to their DNA.

The space sperm and the control group sperm were both used to impregnate female mice via IVF, and all the mouse pups were born healthy, with no significant differences between them. Not only that, the team bred an additional generation to check the health of those pups, too, and found no abnormalities. “The space radiation did not affect sperm DNA or fertility after preservation on ISS, and many genetically normal offspring were obtained without reducing the success rate compared to the ground-preserved control,” they wrote.

Be Part of the Future

Sign up to receive top stories about groundbreaking technologies and visionary thinkers from SingularityHub.

What We Know, What We Don’t

While these results are promising, they’re really just the beginning of our research on reproducing in space, and there are a few important caveats.

For starters, the International Space Station is only about 250 miles from Earth, and it’s partially shielded from space radiation by Earth’s magnetic field. There are a lot more harmful particles flying around as you get farther away, and radiation on Mars is a major concern for human health in general, before even considering its impact on reproduction.

In addition, while five years and ten months is a long time in terms of biological research done in space, it’s not long relative to an average human lifespan; who’s to say what will happen to germline cells inside human bodies when they’re in space for 10 or 20 years, or when they’re born in space? And radiation isn’t the only wild card up there—there’s also microgravity (as if being pregnant and giving birth with gravity’s help wasn’t already hard enough).

One piece of good news? The study found that freeze-drying sperm actually gives the sperm’s nucleus a higher tolerance for radiation as compared to fresh sperm. This could be relevant for sending samples of germline cells to space and preserving or utilizing them there, perhaps to ensure high genetic diversity for future colonies. A project called the Lunar Ark aims to store DNA on the moon as a “modern global insurance policy.”

Since we’re still decades away from human reproduction actually happening off Earth, what’s next in terms of relevant research? The team notes that NASA is planning to launch a multi-purpose outpost to orbit the moon as part of its Artemis program, and they’re hoping to perform similar research with freeze-dried sperm there to study the effects of radiation deeper in space. “These discoveries are essential and important for mankind to progress into the space age,” they wrote.

Image Credit: Teruhiko Wakayama/University of Yamanashi

Vanessa has been writing about science and technology for eight years and was senior editor at SingularityHub. She's interested in biotechnology and genetic engineering, the nitty-gritty of the renewable energy transition, the roles technology and science play in geopolitics and international development, and countless other topics.

Related Articles

Data Centers in Space: Will 2027 Really Be the Year AI Goes to Orbit?

How Scientists Are Growing Computers From Human Brain Cells—and Why They Want to Keep Doing It

Scientists Say We Need a Circular Space Economy to Avoid Trashing Orbit

What we’re reading