Earlier this year, a digital artist conned unsuspecting NFT collectors to highlight a vulnerability in the way cryptographically secured assets are managed online. The anonymous artist, known by their twitter handle @neitherconfirm, sold a collection of stylized portraits as NFTs, but once sold, immediately changed the image file associated with the token to photos of rugs. And not even originals—just watermarked pictures of ugly carpets.

The symbolism wasn’t lost on the crypto community, where “rug pulls” are a well-known scam in which unsuspecting traders are left holding worthless cryptocurrency.

The mostly harmless prank by @neitherconfirm calls attention to the way some NFT file storage relies on centralized mechanisms through which single individuals can still manipulate the data associated with an NFT. Similarly, if a digital marketplace hosting and minting NFTs with centralized addresses later disappears, those NFTs may become worthless. Some collectors buying NFT tweets, for example, learned the hard way that if a tokenized tweet is deleted, they become the proud owner of an NFT pointing to nothing at all.

It’s understandable if you’re skeptical of NFT collecting and wonder whether it’s merely a casino for the crypto elite. Why care about the challenges of NFT data management? Behind the hype, there could be something substantial taking shape. The protocol now widely used to mitigate these issues, called the Interplanetary File System (or IPFS for short), has broader applications, and could fundamentally reshape how all data is managed across the web.

When I recently spoke to Molly Mackinlay, who leads product and engineering at Protocol Labs—a company overseeing the development of IPFS—she suggested the protocol may affect a range of significant sociopolitical systems. IPFS-enabled file preservation and data authentication could impact judicial systems, historical archiving in the digital world, and even bolster the fight against “fake news” and misinformation when trust in journalism is declining.

During our conversation, Mackinlay said today’s internet architecture requires us to trust centralized intermediaries (and those with access to them) not to quietly change online information like news articles, scientific data sets, or images associated with an NFT. But as we’ve seen, the internet is always changing in both obvious and subtle ways.

The early days of the Covid-19 pandemic in the US offers a relevant case in point, when the Trump administration ordered hospitals to send patient data to centralized databases in Washington, bypassing the CDC which traditionally had received such data. The unusual move prompted fears that the data might be altered in politicized ways which could undermine research efforts. There were similar fears that the EPA might modify climate data.

“Understanding which version of a data file you’re accessing should be built directly into data on the internet, and if you need to reference a specific version of an article, image, or scientific data set, you should know if the thing you’re getting back has been altered,” Mackinlay said.

As a protocol, IPFS could yield a more dependable archive for our ephemeral internet. “Ultimately, what we’re talking about is technologically embedding trust right into the protocol itself,” Mackinlay said.

To understand the implications of IPFS, Mackinlay framed it within the development of Web3, a significant shift in the way we design the internet. At its core, Web3 is the return to a decentralized internet. An online world that’s less reliant on centralized institutions and has layers of authentication embedded directly into its architecture. In a 2018 talk, Protocol Labs CEO, Juan Benet, suggested Web3 could do for internet services and applications what Bitcoin hopes to do for money—remove centralized intermediaries while preserving trust.

At its heart, IPFS is a peer-to-peer data storage system (not unlike the original Napster or BitTorrent). Instead of storing files on a central server, data is distributed across a network of participants incentivized to host and verify the legitimacy of the data. Those willing to offer unused hard drive space to store IPFS “objects” are rewarded by a complementary system called Filecoin, a blockchain that oversees payments to those storing files and data.

Another critical aspect of IPFS relates to something called addressing.

Addressing is how internet users access content online. Protocol Labs hopes to swap out the widespread use of location-based addressing with something called “content-addressing.” With location addressing, URLs and domain names point to a specific place where an image file or news article is hosted, and it doesn’t matter to the URL what content is stored there. It can be an NFT of a portrait one day and an ugly carpet the next. Content-based addressing, by contrast, manages data by confirming and verifying what the file is rather than where it’s located.

Every piece of data on the IPFS network is stored as an “object” and given a unique hash (a sort of digital fingerprint). When someone enters an IPFS web address, they are asking the network to show them a file associated with the specific hash entered. And because the data cannot be changed without also changing the hash associated with it, the user can trust that the file returned by the network contains the legitimate data they requested.

For NFT collectors purchasing a file created with IPFS, they can be sure that the NFT is associated with a piece of content that cannot be changed. Here is an example of an NFT’s metadata (which an NFT collector would “own” the record of), and here is the NFT image itself.

Beyond securing the long-term value of NFTs, a range of organizations are using IPFS, including Project Starling, a joint venture from Reuters, Stanford, and USC aiming to boost trust in news media. During Reuters’ coverage of the 2020 US election, photojournalists were given devices that used IPFS to create hashes for photographs and then upload them to Filecoin’s decentralized storage network. In this way, the authenticity of the image was preserved at the point of capture. The hope is that IPFS will make manipulating news images increasingly difficult in the future.

It’s worth noting that IPFS is as much a community of independent node operators as it is a core technology. It’s not clear, for example, how decentralized (and takedown-resistant) file hosting will deal with the inevitable challenges of copyright issues and other more objectionable content. In these cases, Mackinlay pointed out that the burden of responsibility to comply with local and federal laws shifts to individuals participating as nodes on the network, and pointed toward the beginnings of a content moderation mechanism being designed for a decentralized web.

Given the social challenges that centralized platform companies have had in moderating content online, the idea of a public, transparent, and community driven moderation process could even be a welcome change. At a minimum, it’s clearly recognized by the Web3 community as an issue to focus on.

“IPFS is designed around the belief that no one person or company should have unilateral control over all available content on the internet. No node should be forced to host content they don’t want to, and vice versa, no central node controls what the entire network of independent nodes can and can’t host,” Mackinlay said.

As decentralized architecture works to replace the centralized systems of today’s internet, IPFS could grow to power many of the coming products and services at the heart of Web3. While it’s not yet clear whether unfettered decentralization is good for every aspect of our online lives, it’s likely that it will be useful for many things. And for those use cases, IPFS should prove to be a solid protocol for the online world of tomorrow.

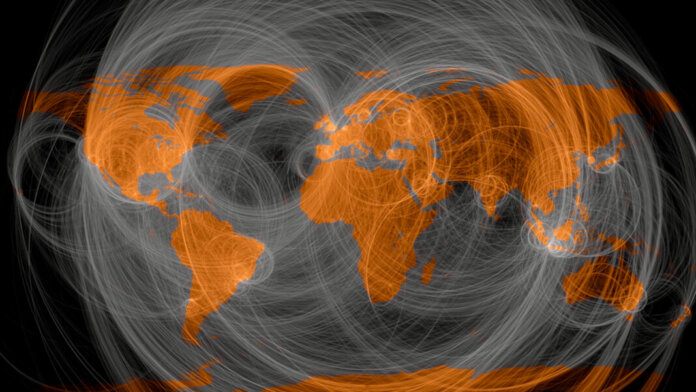

Image Credit: The geography of Twitter replies: The map is a data visualization of how often Twitter users in different locations reply to each to other. Erica Fischer / Flickr