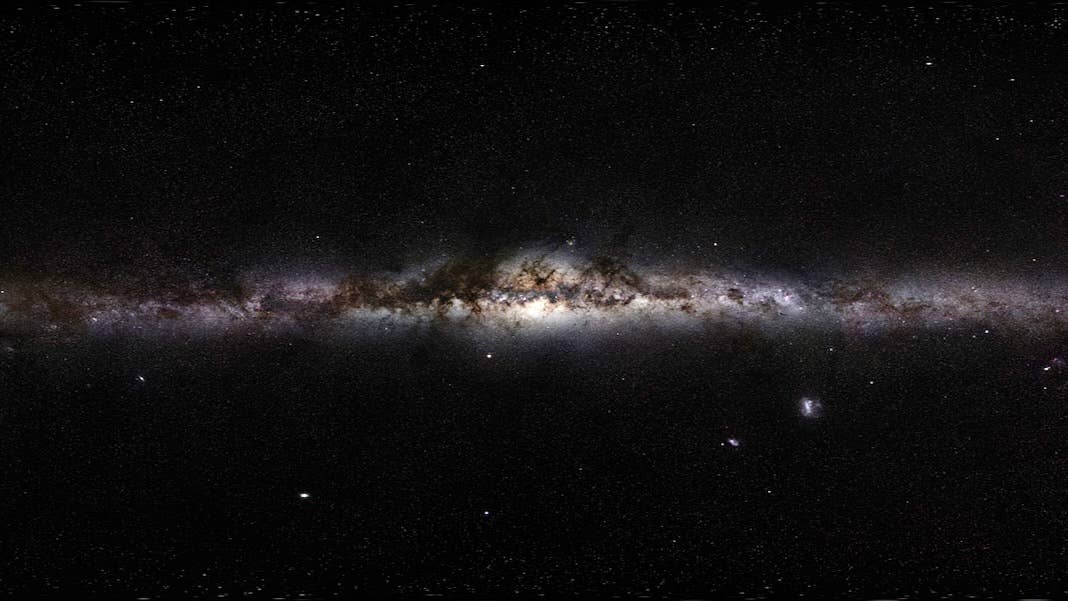

Have We Already Recorded Proof of Alien Civilizations? There’s Only One Way to Know for Sure

Share

My college laptop was slow. It didn't help that the internet was too. Neither fact distracted me from two crucial tasks: downloading music and searching for aliens. The former was a study in patience—tracks spooled out at glacial speeds—the latter a (lazy) labor of love. Scientists had the genius idea of parceling out astronomical data to laptops where a screen saver could comb through them for alien radio signals.

I'm sad to report: None found.

But a lot has changed since then. Computers are faster, software is smarter, and the amount of astronomical data—across the spectrum not to mention gravitational waves—has exploded. It's worth asking: If the data was too much for astronomers to process years ago, what potentially revolutionary signals have we missed since then?

In a recently released report, a team of Caltech and NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory astronomers, led by Joseph Lazio, George Djorgovski, Curt Cutler, and Andrew Howard, argue we can't know for sure unless we change our search strategy to match the times.

Whereas the search for extraterrestrial intelligence (SETI) has been focused on the detection of radio signals—think Jodie Foster with a pair to headphones in the movie Contact—we've since recorded an abundance of data from across the sky and developed tools that can comb it for subtle outliers, from radio signals to unusually bright or flickering objects.

"Ten, twenty years ago, we didn’t have this explosion of artificial intelligence and computation technologies," Anamaria Berea, a computational social scientist at George Mason University not involved in the project, told Wired. "Now they can be used also for archived data."

The idea is two-fold: First, let's widen the search from primarily radio signals to all technosignatures—that is, any telltale signs of technological civilizations, intended or not, from advanced communications to megastructures. Second, let's search for those technosignatures in all current and future observations by training algorithms to spot aberrations and outliers in the data.

A key benefit of such an approach is we "let the data tell us what is in the data," the team writes. Instead of plastering our own biases on the search, we can simply look for anything weird and then take a closer look to figure out why it's different.

At the beginning of the last century, the team say, Marconi, Tesla, and Edison all believed they'd detected radio signals from Mars. They were smart, and wrong. Their judgement was clouded by scientific and technological limits—they didn't know signals in the band detected couldn't get through Earth's atmosphere—and cultural biases—there was a strong popular interest in Mars at the time.

SETI, constrained by resources and availability of data, has suffered biases too. Astronomers could only do so many searches on a limited range of instruments, so they had to decide which lines of inquiry were most valuable. Assumptions have commonly included the idea technological civilizations would choose to signal others civilizations "using mid-20th century technology" coded in ways we would understand.

"Given the diversity of human cultures, including the existence of ancient and medieval documents that have not yet been deciphered or translated, there is reason to doubt the likely success of such heavily biased approaches," the team says.

The new report doesn't dismiss these approaches—radio signals are still a great way to hunt down aliens, and we've only scratched the surface—but the report also suggests new data allows us to widen our search, and new tools can help us reduce inherent anthropocentrism.

Be Part of the Future

Sign up to receive top stories about groundbreaking technologies and visionary thinkers from SingularityHub.

What technosignatures—intended or otherwise—might we keep an eye out for? Beyond radio signals, the report digs into the likes of lasers, megastructures, modulated quasars, and probes in orbit around our sun or sitting unnoticed on the surface of moons or planets.

The Wide-Field Infrared Survey Explorer (WISE) space telescope, for example, completed a detailed all-sky survey in infrared wavelengths ideal for searching out the theoretical heat signatures of Dyson spheres. Scientists have long proposed advanced civilizations might choose to surround their home stars with these megastructures to harvest energy.

Of course, this isn't the first time anyone's thought of using AI in astronomy. On the contrary, AI has a long history classifying galaxies and picking out exoplanets. Scientists recently used it to sharpen the first-ever image of a black hole. SETI has also employed machine learning in its search for radio signals. The new idea here is to comb through everything we've got—even when we don't know what we're looking for.

The standard disclaimers apply: AI is subject to bias too. In this case, it's only as good as the assumptions of its designers and the data it's fed. Careful preparation of information is crucial, alongside the deployment and testing of multiple models, the team writes.

Still, astronomers will have the final say, reviewing whatever outliers the models spit out. These may be naturally caused by some new phenomena, which is still of value, or if we're lucky, they could be the signature of another civilization. Win-win.

Future sky surveys will only add to the pile of sky-wide data to crunch. The Vera C. Rubin Observatory in Chile will observe billions of objects in our galaxy through time. And broader searches for biosignatures—proof of any life, no matter how simple—are getting heated as the James Webb and future telescopes begin to analyze exoplanet atmospheres.

"We now have vast data sets from sky surveys at all wavelengths, covering the sky again and again and again," said Djorgovski. "We’ve never had so much information about the sky in the past, and we have tools to explore it.”

Image Credit: ESO/S. Brunier

Jason is editorial director at SingularityHub. He researched and wrote about finance and economics before moving on to science and technology. He's curious about pretty much everything, but especially loves learning about and sharing big ideas and advances in artificial intelligence, computing, robotics, biotech, neuroscience, and space.

Related Articles

More Space Junk Is Plummeting to Earth. Earthquake Sensors Can Track It by the Sonic Booms.

Researchers Break Open AI’s Black Box—and Use What They Find Inside to Control It

What the Rise of AI Scientists May Mean for Human Research

What we’re reading