Psychedelics Rapidly Fight Depression—a New Study Offers a First Hint at Why

Share

Depression is like waking up to a rainy, dreary morning, every single day. Activities that previously lightened the mood lose their joy. Instead, every social interaction and memory is filtered through a negative lens.

This aspect of depression, called negative affective bias, leads to sadness and rumination—where haunting thoughts tumble around endlessly in the brain. Scientists have long sought to help people out of these ruts and back into a positive mindset by rewiring neural connections.

Traditional antidepressants, such as Prozac, cause these changes, but they take weeks or even months. In contrast, psychedelics rapidly trigger antidepressant effects with just one shot and last for months when administered in a controlled environment and combined with therapy.

Why? A new study suggests these drugs reduce negative affective bias by shaking up the brain networks that regulate emotion.

In rats with low mood, a dose of several psychedelics boosted their “outlook on life.” Based on several behavioral tests, ketamine—a party drug known for its dissociative high—and the hallucinogen scopolamine shifted the rodents’ emotional state to neutral.

Psilocybin, the active ingredient in magic mushrooms, further turned the emotional dial towards positivity. Rather than Debbie Downers, these rats adopted a sunny mindset with an openness to further learning, replacing negative thoughts with positive ones.

The study also gave insight into why psychedelics seem to work so fast.

Within a day, ketamine rewired brain circuits that shifted the emotional tone of memories, but not their content. The changes persisted long after the drugs left the body, possibly explaining why a single shot could have lasting antidepressant effects. When treated with both high and low doses of the psychedelics, lower doses especially helped reverse negative cognitive bias—hinting it’s possible to lower psychedelic doses and still retain therapeutic effect.

The results could “explain why the effects of a single treatment in human patients can be long-lasting, days (ketamine) to months (psilocybin),” said lead author Emma Robinson in a press release.

A Brainy Road Trip

Psychedelics are experiencing a renaissance. Once maligned as hippie drugs, scientists and regulators are increasingly taking them seriously as potential mental health therapies for depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, and anxiety.

Ketamine paved the way. Often used as anesthesia for farm animals or as a party drug, ketamine caught the attention of neuroscientists for its intriguing action in the brain—especially the hippocampus, which supports memories and emotions.

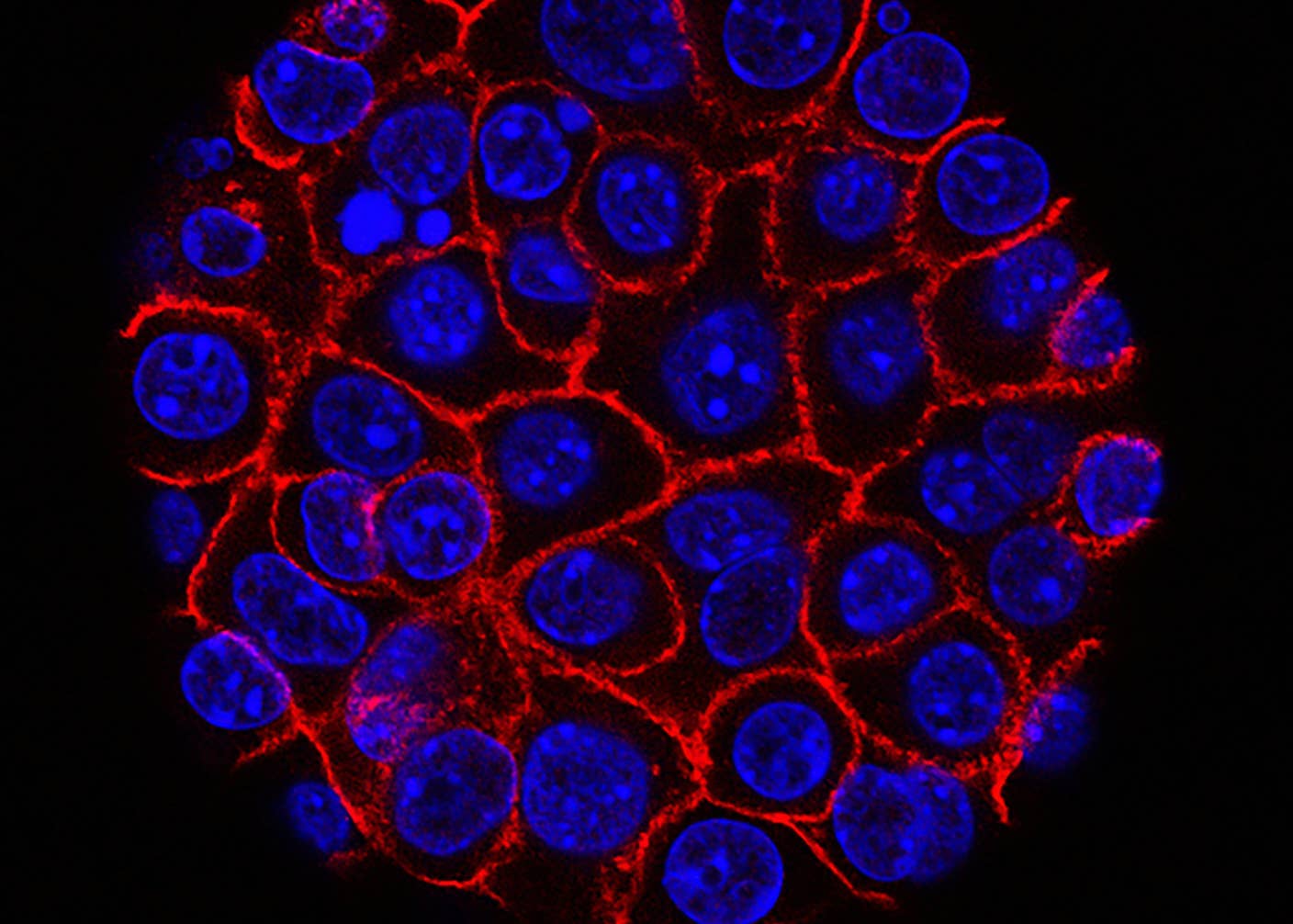

Our brain cells constantly reshuffle their connections. Called “neural plasticity,” changes in neural networks allow the brain to learn new things and encode memories. When healthy, neurons expand their branches, each dotted with multiple synapses linking to neighbors. In depression, these channels erode, making it more difficult to rewire the brain when faced with new learning or environments.

The hippocampus also gives birth to new neurons in rodents and, arguably, in humans. Like adding transistors to a computer chip, these baby neurons reshape information processing in the brain.

Ketamine spurs both these processes. An earlier study in mice found the drug increases the birth of baby neurons to lower depression. It also rapidly changed neural connections inside established hippocampal networks, making them more plastic. These studies in rodents, along with human clinical trials, propelled the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to greenlight a version of the drug in 2019 for people with depression who have tried other antidepressant medications but didn’t respond to them.

While psilocybin and other mind-altering drugs are gaining steam as fast-acting antidepressants, we’re still in the dark on how they work in the brain. The new study followed ketamine’s journey and dug deeper by testing it and other hallucinogens in a furry little critter.

Rat Race

The team started with a group of depressed rats.

Rats aren’t humans. But they are highly intelligent, social creatures that experience a wide range of emotions. They’re empathic towards friends, “laugh” in glee when tickled, and feel low after facing the equivalent of rodent mean girls. Also, scientists can examine their neural networks before and after psychedelic treatments and hunt changes in their neural connections.

Be Part of the Future

Sign up to receive top stories about groundbreaking technologies and visionary thinkers from SingularityHub.

Instead of tackling all aspects of depression, the new study focused on one facet: negative affective bias, which paints life in sad sepia tones. Rats can’t express their emotional states, so a few years back, the same team established a way to measure how they’re “viewing” the world by observing them digging for rewards.

In one trial, the rodents were allowed to dig through different materials—some led to a tasty treat, others not. Eventually, the critters learned their favorite material and how to choose between two best choices. It’s a bit like learning which door to open to get your midnight snack—freezer for ice cream or fridge for cake.

To induce negativity, the team injected them with two chemicals known to reduce mood. Some animals subsequently also had a dose of psilocybin, ketamine, or scopolamine, whereas others got salt water as a control.

When faced with their two favorites, the depressed rats given salt water didn’t seem to care. Despite knowing digging would lead to a treat, they languished when going for their preferred material. It’s like trying to get out of bed when depressed, but knowing you have to eat.

This is “consistent with a negatively biased memory,” the team wrote.

In contrast, depressed rats given a shot of psychedelic acted as they normally would. They went after their favorite pick without a thought. They did experience a “high,” shaking their fur like a wet dog, which is a common sign.

Psychedelics can tamper with memory. To make sure that wasn’t the case here, the team redid the test but without triggering any emotional bias. Rats treated with a low dose of psychedelics shifted their mood towards positivity, without notable side effects. However, higher doses of ketamine inhibited their ability to learn, suggesting there may be an overall effect on memory, rather than mood itself.

Psilocybin stood out amongst the group. When given before a test, the drug shifted the animals’ choices past neutral towards happier outcomes. Even when depressed, they eagerly dug through their favorite materials, knowing it would lead to a reward. Conventional antidepressants can shift negative bias back to neutral, but they don’t change existing memories. Psilocybin seems to be able to “paint over” darker memories—at least in rats.

In a final test, the team directly injected ketamine into the frontal parts of depressed rats’ brains. This region connects extensively with the brain’s memory and emotional centers. The treatment also shifted the rodent’s negative mood towards a neutral one.

To be very clear: The negative bias in the study was induced by chemicals and is not an exact replica for human emotions. It’s also hard to gauge a rat’s emotional state. But the study gave insight into how brain networks change with psychedelics, which could help develop drugs that mimic these chemicals but without the high.

“One thing we are now trying to understand is whether these dissociative or hallucinogenic effects involve the same or different underlying mechanisms and whether it might be possible to have rapid-acting antidepressants without these other effects,” said the team.

Image Credit: Diane Serik / Unsplash

Dr. Shelly Xuelai Fan is a neuroscientist-turned-science-writer. She's fascinated with research about the brain, AI, longevity, biotech, and especially their intersection. As a digital nomad, she enjoys exploring new cultures, local foods, and the great outdoors.

Related Articles

In a First, Researchers Use Stem Cells and Surgery to Treat Spina Bifida in the Womb

These Supercharged Immune Cells Completely Eliminated Solid Tumors in Mice

Souped-Up CRISPR Gene Editor Replicates and Spreads Like a Virus

What we’re reading