This Company Is Growing Mini Livers Inside People to Fight Liver Disease

Share

Growing a substitute liver inside a human body sounds like science fiction.

Yet a patient with severe liver damage just received an injection that could grow an additional “mini liver” directly inside their body. If all goes well, it’ll take up the failing liver’s job of filtering toxins from the blood.

For people with end-stage liver disease, a transplant is the only solution. But matching donor organs are hard to come by. Across the globe, two million people die from liver failure each year.

The new treatment, helmed by biotechnology company LyGenesis, offers an unusual solution. Rather than transplanting a whole new liver, the team is injecting healthy donor liver cells into lymph nodes in the patient’s upper abdomen. In a few months, it’s hoped the cells will gradually replicate and grow into a functional miniature liver.

The patient is part of a Phase 2a clinical trial, a stage that begins to gauge whether a therapy is effective. In up to 12 people with end-stage liver disease, the trial will test multiple doses to find the “Goldilocks” zone of treatment—effective with minimal side effects.

If successful, the therapy could sidestep the transplant organ shortage problem, not just for liver disease, but potentially also for kidney failure or diabetes. The math also works in favor of patients. Instead of one donor organ per recipient, healthy cells from one person could help multiple people in need of new organs.

A Living Bioreactor

Most of us don’t think about lymph nodes until we catch a cold, and they swell up painfully under the chin. These structures are dotted throughout the body. Like tiny cellular nurseries, they help immune cells proliferate to fend off invading viruses and bacteria.

They also have a dark side. Lymph nodes aid the spread of breast and other types of cancers. Because they’re highly connected to a highway of lymphatic vessels, cancer cells tunnel into them and take advantage of nutrients in the blood to grow and spread across the body.

What seems like a biological downfall may benefit regenerative medicine. If lymph nodes can support both immune cells and cancer growth, they may also be able to incubate other cell types and grow them into tissues—or even replacement organs.

The idea diverges from usual regenerative therapies, such as stem cell treatments, which aim to revive damaged tissues at the spot of injury. This is a hard ask: When organs fail, they often scar and spew out toxic chemicals that prevent engrafted cells from growing.

Lymph nodes offer a way to skip these cellular cesspools entirely.

Growing organs inside lymph nodes may sound far-fetched, but over a decade ago, LyGenesis’ chief scientific officer and co-founder, Dr. Eric Lagasse, showed it was possible in mice. In one test, his team injected liver cells directly into a lymph node inside a mouse’s belly. They found the grafted cells stayed in the “nursery,” rather than roaming the body and causing unexpected side effects.

In a mouse model of lethal liver failure, an infusion of healthy liver cells into the lymph node grew into a mini liver in just twelve weeks. The transplanted cells took over their host, developing into cube-like cells characteristic of normal liver cells and leaving behind just a sliver of normal lymph node cells.

The graft could support immune system growth and grew cells to shuttle bile and other digestive chemicals. It also boosted the mice’s average survival rate. Without treatment, most mice died within 10 weeks of the start of the study. Most mice injected with liver cells survived past 30 weeks.

A similar strategy worked in dogs and pigs with damaged livers. Injecting donor cells into lymph nodes formed mini livers in less than two months in pigs. Under the microscope, the newborn structures resembled the liver’s intricate architecture, including “highways” for bile to easily flow along instead of accumulating, which causes even more damage and scarring.

The body has over 500 hundred lymph nodes. Injecting into other lymph nodes located elsewhere also grew mini livers, but they weren’t as effective.

Be Part of the Future

Sign up to receive top stories about groundbreaking technologies and visionary thinkers from SingularityHub.

“It’s all about location, location, location,” said Lagasse at the time.

A Daring Trial

With prior experience guiding their clinical trial, LyGenesis dosed a first patient in late March.

The team used a technique called endoscopic ultrasound to direct the cells into the designated lymph node. In the procedure, a thin, flexible tube with a small ultrasound device is inserted through the mouth into the digestive track. The ultrasound generates an image of the surrounding tissue and helps guide the tube to the target lymph node for injection.

The procedure may sound difficult, but compared to a liver transplant, it’s minimally invasive. In an interview with Nature, Dr. Michael Hufford, CEO of LyGenesis, said the patient is recovering well and already discharged from the clinic.

The company aims to enroll all 12 patients by mid 2025 to test the therapy’s safety and efficacy.

Many questions remain. The transplanted cells could grow into mini livers of different sizes, based on chemical signals from the body. Although not a problem in mice and pigs, could they potentially overgrow in humans? Meanwhile, patients receiving the treatment will need to take a hefty dose of medications to suppress their immune systems. How these will interact with the transplants is also unknown.

Another question is dosage. Lymph nodes are plentiful. The trial will inject liver cells into up to five lymph nodes to see if multiple mini livers can grow and function without side effects.

If successful, the therapy has wider reach.

In diabetic mice, seeding lymph nodes with pancreatic cellular clusters restored their blood sugar levels. A similar strategy could combat Type 1 diabetes in humans. The company is also looking into whether the technology can revive kidney function or even combat aging.

But for now, Hufford is focused on helping millions of people with liver damage. “This therapy will potentially be a remarkable regenerative medicine milestone by helping patients with ESLD [end-stage liver disease] grow new functional ectopic livers in their own body,” he said.

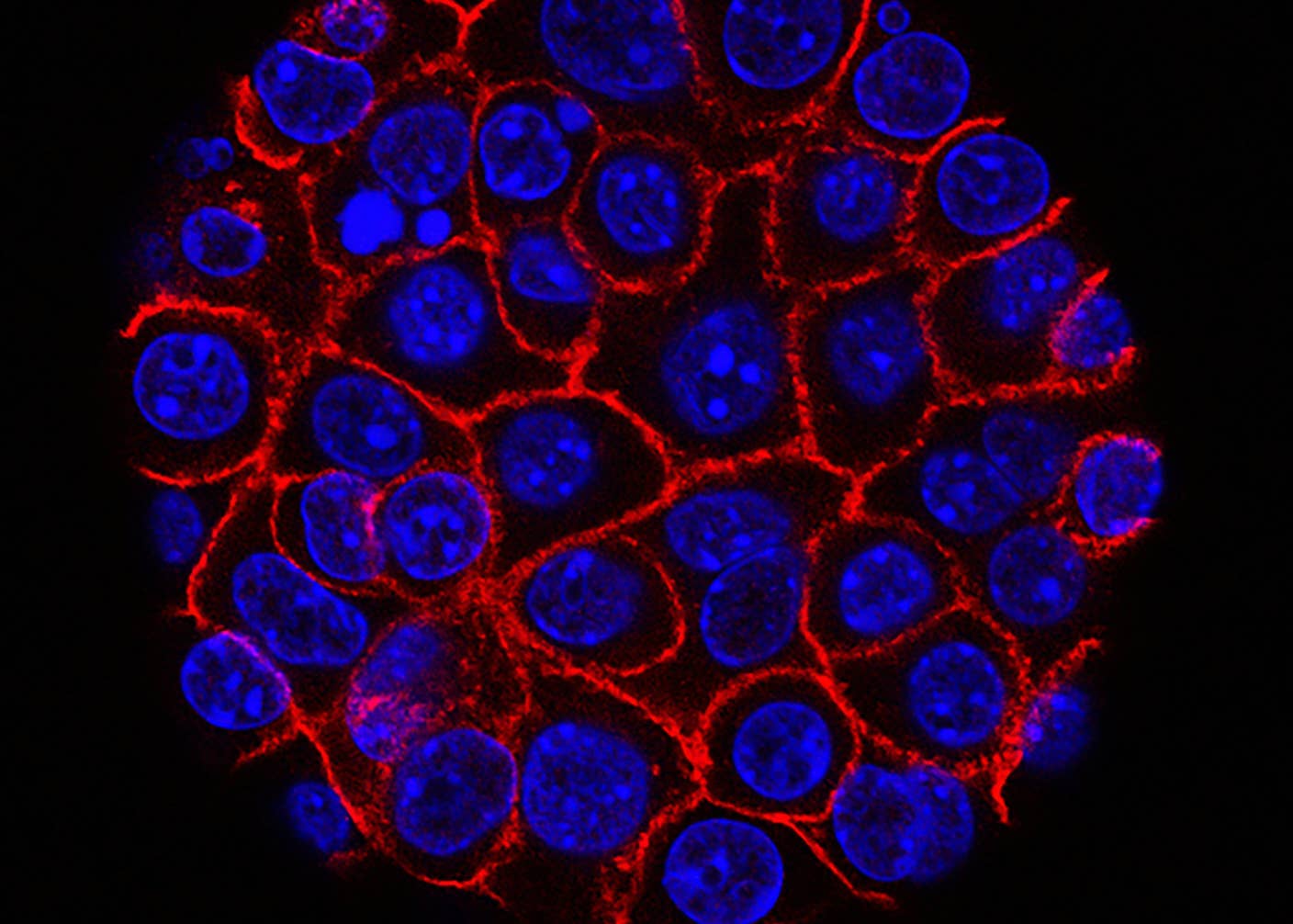

Image Credit: A solution with liver cells in suspension / LyGenesis

Dr. Shelly Xuelai Fan is a neuroscientist-turned-science-writer. She's fascinated with research about the brain, AI, longevity, biotech, and especially their intersection. As a digital nomad, she enjoys exploring new cultures, local foods, and the great outdoors.

Related Articles

These Supercharged Immune Cells Completely Eliminated Solid Tumors in Mice

Souped-Up CRISPR Gene Editor Replicates and Spreads Like a Virus

Your Genes Determine How Long You’ll Live Far More Than Previously Thought

What we’re reading