For the first time, an off-the-shelf CAR T cell therapy has been used to treat potentially life-threatening autoimmune disorders in three people. With a single shot, the treatment rapidly reversed their debilitating symptoms for up to a year.

The treatment changed one recipient’s life. Diagnosed with systemic sclerosis—an autoimmune condition that wrecked his muscles and joints—the 57-year-old man, who the study identifies by his last name, Gong, regained his life just two weeks after the injection. He could move the muscles around his mouth to smile. His fingers again danced across a keyboard at work.

After a year, he told Nature, “I feel very good.”

Gong is part of an ongoing clinical trial to genetically reprogram healthy donor cells into a universal “living drug.” The trial, set to end in 2025, could upend current interventions for untreatable autoimmune disorders. These life-long diseases are mostly managed, but not cured, with immunosuppressant drugs. Though helpful, the medications drastically lower a person’s ability to battle infectious diseases, making it hard to fight off bacterial or viral attacks.

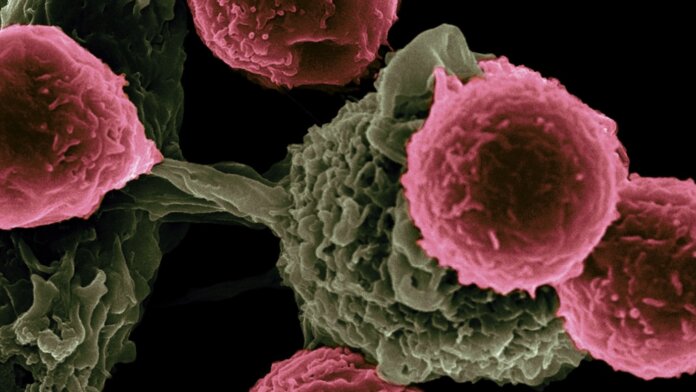

Chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cell therapies take a different approach.

Here, immune cells called T cells are genetically engineered to hunt targets inside the body, including rogue immune cells that destroy the body’s own tissues. The treatment is generally tailored for each person. The new study hints that personalization isn’t always necessary—we might be able to mass produce living drugs in the future and thereby slash costs.

A CAR T Refresher

CAR T therapy is perhaps best known for its revolutionary ability to tackle previously untreatable blood cancers.

Here’s how it usually works. A patient’s immune cells are extracted and genetically engineered to produce specific protein “guides” that attach to the surface of each cell. These guides help the cells home in on cancers and alert the body’s immune system to ramp up attacks.

It’s been a game-changer for blood cancer. The FDA has already approved half a dozen CAR T therapies. Newer studies have tried directly reprogramming immune cells inside the body. The therapy has “been hailed as one of the greatest breakthroughs,” wrote the authors.

But CAR T has more tricks up its sleeve. For nearly a decade, scientists have believed it could tackle autoimmune diseases that turn the immune system against itself in a civil war.

It’s a tale of two types of immune cells, T and B cells. Normally, B cells pump out antibodies that grab onto invading pathogens and tag them for elimination. But in autoimmune diseases, they mark healthy tissues as the foe, alerting T cells to destroy them and causing the body to attack itself. CAR T cells that target these defective B cells could nip autoimmune problems in the bud.

Making the body fight itself sounds irrational, but the idea seems to work. A therapy for anti-synthetase syndrome, an autoimmune disease that wrecks the lungs and muscles, improved breathing and mobility in patients in just three months. Similar therapies have also tackled pemphigus vulgaris, a deadly autoimmune condition that causes the skin to gradually peel off.

Despite its promise, CAR T has a problem. Because each treatment is tailored to the person, the process is expensive and time consuming. Currently approved treatments cost in the hundreds of thousands of dollars in the US. While India is making cutting-edge CAR T therapies for cancer around one-tenth the cost, low-cost treatments aren’t available for autoimmune disorders.

One way to slash costs and accelerate production is to nix personalization altogether. A more efficient way to make CAR T cells is to use immune cells from healthy donors. Like a plug-and-play Mr. Potato head, the cells can be given genes to increase immune attacks on cancer cells—or to dial down friendly fire from autoimmune flare-ups.

Plug and Play

In the new study, researchers harvested immune T cells from a single donor: A healthy 21-year-old woman. They reprogrammed the donated cells with a single gene that tackles the overzealous B cells behind two autoimmune diseases.

The first, immune-mediated necrotizing myopathy (IMNM) attacks muscles and generally can’t be treated with medications. The other, systemic sclerosis, is especially harrowing as it damages internal organs and causes irreversible scarring around the heart and kidneys.

Using the gene editor CRISPR-Cas9, the team wiped out five genes in the donor T cells to prevent them from attacking host cells and protect them from the host’s immune system. The cells were also engineered to go after dangerous B cells triggering autoimmune responses.

The study recruited three people between the ages of 42 and 56, two suffering from systemic sclerosis and one with IMNM. After injection, the CAR T cells multiplied and destroyed targeted B cells. Most of the engineered cells survived for weeks inside the body before dwindling—something often seen in this type of therapy.

But it worked.

The IMNM patient’s symptoms completely disappeared two months after treatment, and she remained symptom-free for at least six months. She regained the use of her muscles and reported a better quality of life. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans of her thigh muscles showed reduced swelling and inflammation.

Over time, her B cells returned to normal levels. But rather than causing disease, the cells were healthy and fought off pathogens instead of attacking her own body.

The two other people with systemic sclerosis also saw improvements. Their symptoms steadily improved two months after treatment and that lasted for at least half a year. The engineered cells rejuvenated scarred skin and lung tissue and restored it to a younger, healthier version.

In all three people, antibodies that attack healthy tissue dropped to nearly undetectable levels.

“The clinical outcomes are phenomenal,” Dr. Lin Xin at Tsinghua University, who was not involved in the work, told Nature.

Way Forward

Though it’s promising, the study is very small. The team plans to further test the treatment on around 15 people with autoimmune disorders.

However, its safety profile held up. One concern with CAR T therapy is a runaway immune response called a “cytokine storm.” Here, the body damages healthy tissues with a hefty dose of immune molecules meant to attack the CAR T invaders. In all three participants, the engineered cells worked as expected with minimal side effects.

Cancer is another concern. A handful of cancer patients receiving engineered cells developed new tumors months to years after treatment. It’s still debatable whether the cancers were due to the CAR T cells, but the team is aware of the risk.

They’ll follow up with the three patients to gauge the therapy’s effects and safety and recruit more patients for the clinical trial.

Eventually, the researchers want to compare off-the-shelf CAR T cells to those engineered from individuals, both in terms of how well they work and how much they cost. Developing a universal treatment, versus a personalized one, could lead to a new generation of affordable, adaptable, and safe “living drugs” that can keep autoimmune disorders in check.

Image Credit: NIH via Flickr