With a brain-stimulating procedure to relieve Parkinson’s disease and epilepsy and another that purports to prevent Alzheimer’s disease, it was only a matter of time before neurostimulation became an accepted treatment for migraine headaches, which affect about 1 in 10 people worldwide.

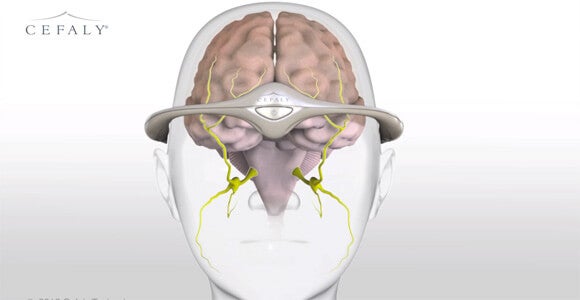

The FDA recently approved an external device that uses nerve stimulation to decrease the frequency of debilitating migraine headaches. The Cefaly headband, which connects to a stick-on electrode to stimulate the endings of the trigeminal nerve, is the first non-pharmaceutical treatment for chronic migraines to get the agency’s okay.

“Cefaly provides an alternative to medication for migraine prevention. This may help patients who cannot tolerate current migraine medications for preventing migraines or treating attacks,” Christy Foreman, director of device evaluation at the FDA’s Center for Devices and Radiological Health, said in a statement.

“Cefaly provides an alternative to medication for migraine prevention. This may help patients who cannot tolerate current migraine medications for preventing migraines or treating attacks,” Christy Foreman, director of device evaluation at the FDA’s Center for Devices and Radiological Health, said in a statement.

Cefaly, made by the Belgian company STX-Med, was already approved for sale in Europe and has sold roughly 50,000 units.

Migraine sufferers wear the headband for 20 minutes a day and can go about their daily routines as they do so. A 67-person clinical trial cited by the FDA showed that wearers experienced fewer headaches in a month. However, the device doesn’t prevent all migraines and, despite the company’s claims to the contrary, the FDA found no evidence that it relieves the pain of a migraine already in progress.

Patients experience a mild tingling sensation on their forehead while the headband is active. Some users disliked the sensation enough to discontinue use, but among the existing European users, more than half say they plan to continue using Cefaly.

Cefaly’s innovation is not neurostimulation, but neurostimulation without surgery to install the device.

Cefaly’s innovation is not neurostimulation, but neurostimulation without surgery to install the device.

Medical devices far more sophisticated than the anti-migraine headgear confront the same challenge: Researchers are developing a number of prosthetic devices that hook into the patient’s nervous system, but most require surgery.

For instance, Switzerland’s EFPL is testing a prosthetic hand that sends some sensory information back to the brain, giving the patient the illusion of feeling with the artificial hand. Cambridge scientists have proposed a neuroprosthetic bladder that would allow quadriplegics to control elimination with the touch of a button.

But in amputees and quadriplegics, the cost-benefit equation of surgical implantation is quite different than it is for those who suffer migraines, which, however miserable, do not threaten the patient’s long-term health.

Inquiries into brain-to-machine interfaces also rely on successfully linking nerves and machines together. Many are also currently focused on providing services for patients with paralysis due to the invasive installation. But if they are to gain acceptance among the general population, non-surgical hookups will likely be necessary.

Images: STX-Med, 9nong via Shutterstock.com