Patient’s Cranium Replaced With Custom 3D Printed Implant

Share

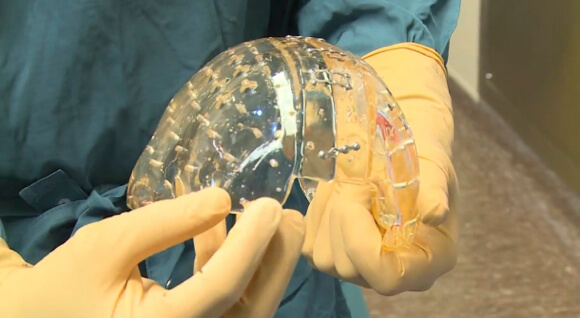

Three months ago, a 22-year-old woman, suffering from a rare bone ailment, underwent brain surgery in Holland. Her skull, which had grown some three times thicker than average, was putting pressure on her brain, causing loss of vision and motor skills.

Left unchecked, she would have died from the condition. Instead, thanks to a 3D printed skull implant, her vision has been restored, and she’s back at work with no complaints.

Just a few years ago, there would have been no effective treatment for the patient’s disorder, according to Dr. Bon Verweij of the University Medical Center Utrecht. In the past, implants were hand constructed in the operating room out of a type of cement. They tended to be ill-fitting at best. But now doctors can generate a 3D model of a patient’s skull and then print a precise, custom-fitted plastic implant.

“This has major advantages, not only cosmetically,” says Verweij, “But also because patients often have better brain function compared with the old method."

The UMC Utrecht press release claims it’s the first ever complete skull replacement, but that's a little misleading.

The skull is composed of the cranium and the facial skeleton. The surgeons replaced almost all of the cranium (presumably, they needed bone to attach the implant). Yet it’s not the first such procedure. Last year, we wrote about an American patient who had 75% of his cranium replaced with an FDA-approved 3D printed implant.

Although both implants are plastic, the American implant, made by Oxford Performance Materials, is opaque and has the look of dried clay, while the Dutch implant, made by Australian firm Anatomics, is transparent. The implants are attached with titanium clasps and screws, and once secure, the scalp is re-attached.

“There are almost no traces that she had any surgery at all,” says Verweij.

Though in this particular case the woman's condition is rare, 3D printed implants may prove more widely useful for other bone conditions and those suffering skull damage and brain swelling after an accident or caused by tumors. (To see more of the procedure, check out the video below—but be forewarned, it contains graphic images of the brain.)

Be Part of the Future

Sign up to receive top stories about groundbreaking technologies and visionary thinkers from SingularityHub.

It’s often said 3D printing will revolutionize 21st century manufacturing, but its potential in medicine is less heralded—personalized body parts and prosthetics can improve recovery, functionality, cosmetics, and reduce procedure time and cost too.

After a 2012 motorcycle accident, for example, 29-year-old Stephen Power underwent reconstructive surgery. Doctors used 3D models of the patient’s face to plan the surgery, 3D printed drilling and cutting guides to reduce the chances of error, and 3D printed titanium implants to support Power’s bone structure.

Two years ago, a 3D printed custom implant saved a six-week old baby boy’s life. Suffering from a rare condition causing the cartilage of the trachea to soften and collapse, the boy stopped breathing at dinner. The FDA fast-tracked approval of a procedure to implant a custom 3D printed stint to keep his airways open.

Other medical uses include 3D printed scaffolding to grow prosthetic ears and 3D printed parts for affordable prosthetic hands. Even more impressive, firms like Organovo are developing technology to print living tissue, even entire organs.

Medical 3D printing isn't ubiquitous, but there are more examples each year. In the case of skull implants, thousands of patients in just the US and Europe alone stand to benefit.

Image Credit: UMC Utrecht/YouTube

Jason is editorial director at SingularityHub. He researched and wrote about finance and economics before moving on to science and technology. He's curious about pretty much everything, but especially loves learning about and sharing big ideas and advances in artificial intelligence, computing, robotics, biotech, neuroscience, and space.

Related Articles

This Week’s Awesome Tech Stories From Around the Web (Through February 14)

Vast ‘Blobs’ of Rock Have Stabilized Earth’s Magnetic Field for Hundreds of Millions of Years

Elon Musk Says SpaceX Is Pivoting From Mars to the Moon

What we’re reading