You have a right to the internet…maybe even a fast internet. In a breakthrough report to the 17th session of the United Nations’ Human Rights Council, UN Special Rapporteur Frank La Rue from Guatemala called for governments of the world to protect citizens’ access to the internet as a key tool for enabling their human rights. Open and anonymous online discourse has rapidly become one of the driving forces in political change around the world. In the aftermath of Iran’s election protests, WikiLeaks scandals, and Egyption revolutions, blogs and tweets are now tools for social justice. La Rue wants them to be available to people no matter the political climate of their homeland. The “Report of the Special Rapporteur on the promotion and protection of the right to freedom of opinion and expression” has already generated a wave of responses from media sources, on and offline. Yet as the UN moves to pressure its governments for freedom of expression on the internet, I’m left wondering if we aren’t missing half the issue. Open and anonymous is important, but so is fast and cheap. What good is protecting our freedom of online speech when most of us can’t even get online in the first place?

La Rue’s report to the UN is a powerful statement for the rights of individuals in the modern age. There’s little doubt that he sees online speech as one of the defining elements of enfranchisement, and that like freedom of the press in the 20th century, maintaining freedom of the internet will be integral to preventing states from oppressing their citizens in the 21st century:

“In recent months, we have seen a growing movement of people around the world who are advocating for change – for justice, equality, accountability of the powerful and better respect for human rights. However, the unique features of the Internet, which allow individuals to spread information instantly, to organize themselves, and to inform the world about situations of injustice and inequality, have also created fear among Governments and the powerful.” — Statements to the Human Rights Council, Frank La Rue, June 3, 2011.

We’ve recently discussed how Facebook, Google, and many other large name corporations provide governments with access to users’ information, mostly in the context of criminal investigations. Yet La Rue and his team highlight how this backdoor access is one of the ways in which states are limiting internet freedom. The report continually points to the efforts of governments to stem the tide of free and anonymous online expression as what it is: a fight to maintain power, especially power over information:

“The Special Rapporteur remains concerned that legitimate online expression is being criminalized in contravention of States’ international human rights obligations, whether it is through the application of existing criminal laws to online expression, or through the creation of new laws specifically designed to criminalize expression on the Internet. Such laws are often justified on the basis of protecting an individual’s reputation, national security or countering terrorism, but in practice are used to censor content that the Government and other powerful entities do not like or agree with. “

The UN’s take on online freedom is a bold one because it points fingers at everyone, and it’s unclear who would back real change in the assembly. The EU is planning on massive online tracking systems, ostensibly for the ongoing fight against terrorism. Certainly the members of the Security Council aren’t known for playing nice on the internet, either. The UK, France and the US may be upping their policing of the internet by considerable margins with new calls for a ‘civilized internet‘. In its fight with WikiLeaks the United States has repeatedly shown that its love for anonymous online discussions has its limits. La Rue reports that 109 prominent bloggers have been recently jailed for their statements, and 72 of those lived in China. That leaves Russia, which is known as the home of hackers, spam, and hilarious opulence.

Whether or not it has any strong hopes of enacting real change, the UN’s report calls states to promote online freedoms in five key ways (paraphrased):

- Protect citizen’s rights to speak anonymously on the internet.

- Refrain from building, using, or enforcing real-name databases that link online activity to user identity (even those used by popular companies like Facebook).

- Acknowledge that national security and anti-terrorism concerns can’t be used to restrict freedom of expression except in the most dire circumstances where there is an imminent and legitimate threat.

- Take meaningful steps to ensure the privacy of personal data.

- Decriminalize defamation.

I agree deeply with the sentiments in the La Rue report, and would be ecstatic if governments around the world, including my own, took more visible and active steps to ensure online freedom of expression. Open and anonymous discourse is one of the key ingredients that allow the internet to be used as a tool for change. Yet it’s not until the conclusion of the UN report that I think we see that it’s only half finished:

“Given that access to basic commodities such as electricity remains difficult in many developing States, the Special Rapporteur is acutely aware that universal access to the Internet for all individuals worldwide cannot be achieved instantly…”

“…Given that the Internet has become an indispensable tool for realizing a range of human rights, combating inequality, and accelerating development and human progress, ensuring universal access to the Internet should be a priority for all States.”

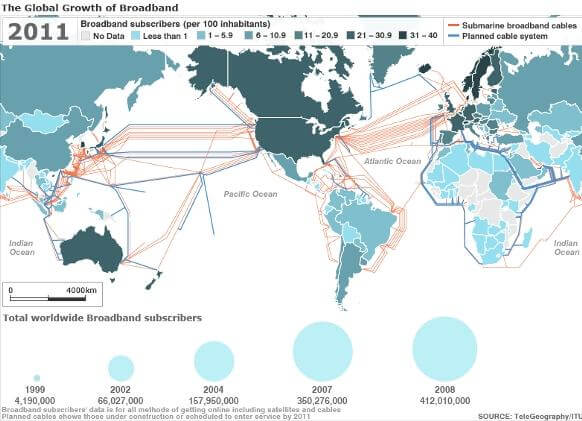

The global population is above 6.7 billion, yet less than a third of us have regular access to the internet. According to Point Topic, of those 2 billion internet users only about 500 million have access at broadband speeds. I’m not such a spoiled westerner that I consider connecting through dial up modems or non-smart phones a travesty to justice, but there is a visceral difference when you read about news and when you can watch news happen. A man gets beaten to death for defying a government’s corrupt policy – those who read about it may be outraged but those who watch the video of it happen will f*cking riot. Until users have access to rapid video sharing, live streamed podcasts, and up to the second tweets/status updates/etc, they are only experiencing a fraction of what the internet has to offer, and they can only wield a portion of the power it provides.

If internet speech is a human right, then we must concern ourselves with internet access as much as we do about government filtering and control. Nations like Finland were some of the first to guarantee broadband internet to its peoples, but now the UK, Australia, and others are moving to do the same. According to Net Index, South Korea, and parts of Europe lead the pack in average internet speeds. The top ten nations zip along at 23 Mbps or more but the vast majority of the world is well below 1 Mbps. The truth is that it’s going to take major investments in infrastructure to give the world’s citizens high speed access.

Just look at the US. Despite being the home for Google, Microsoft, and so many other big names, we never top the lists for speed, adoption, or penetration rates. Some of us will have access to gigabit connections, while other will face speeds, data limits, and accessibility issues that are ripe for comedy. When even a commercially powerful nation like the US is lagging when it comes to providing internet infrastructure to its citizens, what does that say about hope for internet access on the global level?

The saving grace may be in your pocket. While we’ve only two billion or so internet users, we have a whopping five billion mobile phone users. (As someone whose birth coincided with the birth of mobile technology, that fact always floors me.) With each new generation of phones we are given devices that are cheaper, faster, and more reliable. Every year, more of these phones are also capable of browsing the web. It’s very possible that phone adoption rates will be the determining factor when it comes to internet accessibility. Especially as mobile technology allows us to approximate reasonable broadband speeds on wireless connections. However we expand access to the internet, we need to do it now. E-commerce in the US economy alone is expected to near $200 billion this year, and the value of online activity in social, political terms is immeasurable.

Global internet use is expected to quadruple in the next four years with boosts from both private and public sectors. How will the fight for internet rights shift as more and more of us come online? La Rue’s report warns us that citizens that are blocked from accessing whatever parts of the internet they want (open) and commenting as they see fit (anonymous) are facing de facto oppression of their freedom of speech and press. I worry that broadband access (fast) and competitive infrastructure (cheap) aren’t sufficient to provide the expressive internet La Rue promotes. No matter how far we advance in internet adoption, however, those four pillars of a free internet will remain vulnerable. Whether we lose open access, as seen when China blocks sites from search results, or anonymity, as the US does when persecuting WikiLeaks, or speed, as denial of service attacks do regularly, or costs, as the economy and lack of competition do all the time, the results are the same: citizens of the world lose power.

I think that the future holds some hard questions for us as internet users. If we don’t provide affordable internet access to everyone, are we blocking democracy and political power? Does that mean we have to subsidize the internet (either in its infrastructure, or its service providers, or both)? When a country takes down any of the four pillars of the free internet, how will other countries respond? At some point will South Korea and Finland have moral obligations to sanction countries just because they have such slow download rates? For that matter, given how important e-commerce will be in the years ahead, will the slow download speeds be a sanction on their own?

Perhaps the one thing I know for certain is that Mr. La Rue’s sentiment in his report is right: the internet can be a transformative tool for justice, and it’s up to the people of the world to promote and protect it. Without that power, citizens can be left at the mercy of horrific regimes. I was appalled at the news that North Korea was keeping more than 200,000 of its people in slave camps. We don’t even know how terrible situations were there because organizations like Amnestry International had to base their estimates off of satellite images and a handful of first person accounts. Could you imagine such an atrocity going unchecked for so many years if every North Korean had a mobile phone with a video camera and access to the internet?

The push for a faster, cheaper, more open, and anonymous internet is a smart one, with great financial and cultural rewards. La Rue’s United Nations report, however, makes me believe that it might just be a noble pursuit as well.

[image credits: Vincent Diamante via WikiCommons, BBC, other images in public domain]

[source: Report of the Special Rapporteur on the promotion and protection of the right to freedom of opinion and expression, Frank La Rue (PDF), The UN Office of the High Commission for Human Rights]