New Techinique Makes IVF Dramatically Cheaper, More Accurate

Connor Levy is proof of concept. Barely two months old, Connor is the first child born from an embryo screened with next-generation DNA sequencing techniques to ensure that doctors provided his mother, Marybeth Scheidts, 36, with a genetically viable fertilized egg. The new process is dramatically cheaper and has initially proven at least as effective as the genetic methods fertility clinics use now.

Share

Connor Levy is proof of concept. Barely two months old, Connor is the first child born from an embryo screened with next-generation DNA sequencing techniques to ensure that his mother, Marybeth Scheidts, 36, got a genetically viable fertilized egg. The new process is dramatically cheaper and has initially proven at least as effective as the genetic methods fertility clinics use now.

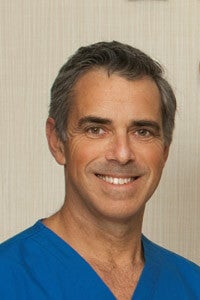

Dr. Dagan Wells, an Oxford University medical researcher, pioneered the approach that Scheidts and her husband, David Levy, 42, used to conceive Connor.

Wells and his team used next-generation DNA sequencing methods to screen the embryos of Scheidts and Levy, who were treated at Main Line Fertility Clinic outside Philadelphia, and another couple, who were treated at New York University's fertility clinic and are still awaiting the birth of their child.

Since its introduction in the late 1970s, in vitro fertilization, or IVF, has remained an expensive last resort for those who have trouble conceiving. And even so, IVF's success rate for American women aged 35-37 is under 35 percent.

Many IVF embryos, produced by mixing sperm and surgically removed ova in a laboratory, suffer chromosomal abnormalities that prevent them from implanting in the uterus or developing to term. The abnormalities don't always show up under a microscope before it's time to implant one or several embryos.

Despite growing availability and falling costs, next-generation sequencing methods have not been applied to IVF embryos because researchers can only safely remove a single cell from each embryo without risking destroying it.

Wells's team tackled that problem by sequencing the cells from multiple embryos at the same time. Researchers added short DNA tags, or "barcodes," to the genetic material from each embryo to ensure they could connect the correct result to right embryo. They sequenced about two percent of each embryo's genome, which is enough to determine whether it has the right number of chromosomes but insufficient to analyze specific genes.

The current genetic method Main Line uses, called comparative genomic hybridization, costs somewhere in the vicinity of $5,000. Wells's method, which taps newer DNA sequencing methods developed with cost in mind, could cut the price down as low as $1,000, according to Michael Glassner, the head of the Main Line infertility division.

The price difference could make testing possible for many more couples.

"We just couldn't afford genetic testing; it was too much money out of pocket for us. The study afforded us a better opportunity to know which embryos would actually give us a child," Levy told Singularity Hub.

Levy and Scheidts found themselves in the right place at the right time to participate in the early trial of Wells's approach. The Main Line clinic had been alerted Wells was looking for volunteers because it does a lot of genetic screening, said Glassner.

After several years of trying to conceive, Scheidts and Levy produced 13 embryos in their first attempt at IVF at Main Line, all of which developed normally for the first five days. Doctors knew many of the embryos would likely have genetic defects, but with all looking equally healthy under a microscope, they didn't know which embryos to transfer to Scheidts.

"My wife was in the facility to do the transplant that day, and the doctor came in and said, 'Listen, you hit the lottery,'" Levy said.

The test procedure could help make the call, and the large number of embryos would maximize the usefulness for the researchers.

Be Part of the Future

Sign up to receive top stories about groundbreaking technologies and visionary thinkers from SingularityHub.

After the couple agreed to participate in the experiment, their embryos were first subjected to conventional genetic screening (at no cost) to provide a point of comparison for Wells's approach. The screening ruled out all but four embryos. The embryos were then shipped to Wells in the UK, where just three were deemed viable.

Glassner was so confident that any of the three sound embryos would result in a child that he transferred only one to Scheidts, Levy said. Fertility doctors often transfer several embryos to improve the odds that their female patients will get pregnant, but the practice often results in riskier multiple births. Pre-screening embryos can boost the chance of success from a given round of IVF by as much as half; it also reduces the chance of miscarriage by half, Glassner said.

Wells's approach will next be tested in clinical trials. If the method holds up with a control group and larger sample size—and is eventually given the green light for wider use—it could increase the number of babies born through IVF , even as it might reduce the number of multiple births.

"Since this broke, we've had calls from all over the world from patients who want to get involved in the clinical trial. It's made patients very aware of the genetic reality of embryos," Glassner told Singularity Hub.

If more patients opted for genetic screening, the number of embryos in cryogenic storage could also drop, since few couples would opt to store those that are found nonviable. Main Line alone has 8,000 frozen embryos.

"They create a moral dilemma," Glassner said.

Of course, another moral dilemma will be what to do with the information next-generation DNA screening can provide. The next logical use of the technology would be to reveal the chances of disease encoded in the embryos, Wells says, steering parents to healthy babies. Soon the door opens onto parents choosing embryos based on height, eye color and the like, Glassner said.

But for now, Wells's technique realistically just shortens IVF by a few cycles and puts it within reach for more aspiring parents.

Photos: Connor Levy by Jaimie Miele; Dagan Wells courtesy Oxford University; embryo by Harimiao via Wikimedia Commons; Michael Glassner courtesy Main Line Fertility Clinic

Cameron received degrees in Comparative Literature from Princeton and Cornell universities. He has worked at Mother Jones, SFGate and IDG News Service and been published in California Lawyer and SF Weekly. He lives, predictably, in SF.

Related Articles

This Light-Powered AI Chip Is 100x Faster Than a Top Nvidia GPU

This Week’s Awesome Tech Stories From Around the Web (Through December 20)

Data Centers in Space: Will 2027 Really Be the Year AI Goes to Orbit?

What we’re reading