In the search for forms of identification that can’t be forged, biometric scans have been an enduring source of interest.

In the search for forms of identification that can’t be forged, biometric scans have been an enduring source of interest.

But which parts of an individual’s anatomy are truly unchangeable, even as he or she ages and potentially undergoes plastic surgery?

As far back as the late 1980s, the U.S. Patent Office issued its first patent for iris recognition scans. (Retinal scans, though widely talked about, are not as widely used as iris scans.) The Canadian Border Services offer an opt-in expedited security program that relies on an iris scan. And India’s ambitious national identification program, which relies heavily on biometric methods to serve a population that includes a huge number of illiterate people, uses iris scans among other methods.

But some researchers who have studied iris-scanning technology have found too much variety in the scans generated over time by a single person.

It now appears that those studies simply pointed to how not to do iris scans, according to a new meta-analysis by the National Institute of Standards and Technology. The report concludes that, done properly, iris scans offer a stable means of biometric identification for up to a decade at a time.

Yes, even the iris is affected by aging, which causes pupils to shrink slightly. But that need not preempt use of the iris as a biometric identifier. Participants in eye-based identification programs can be required to provide a new baseline scan every 10 years — similar to existing requirements for many forms of government photo ID.

Yes, even the iris is affected by aging, which causes pupils to shrink slightly. But that need not preempt use of the iris as a biometric identifier. Participants in eye-based identification programs can be required to provide a new baseline scan every 10 years — similar to existing requirements for many forms of government photo ID.

India’s program, however, allows citizens to use the same scan throughout their lifetime.

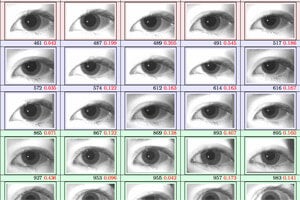

The NIST analysis found that the variance identified in previous studies, including one at Notre Dame that scanned students’ eyes, stemmed mainly from varying environmental conditions rather than changes to the iris itself. The analysis also looked at data from Canada’s iris recognition program.

The direction of the person’s gaze and how dilated his or her pupils were, for example, could result in a scan that appeared too different from the baseline scan to verify the person’s identity. Scanning equipment that controls these factors could rule out the false negatives, NIST concluded.

Still, iris scans aren’t a slam-dunk method of biometric ID — at least not yet. The NIST didn’t delve into how to control for lighting and the direction of the subject’s gaze. And the cornea, which covers the iris, can alter the image of the iris somewhat as it changes in shape. Cataract surgery can also cause the iris to change dramatically, at least temporarily.

Still, iris scans aren’t a slam-dunk method of biometric ID — at least not yet. The NIST didn’t delve into how to control for lighting and the direction of the subject’s gaze. And the cornea, which covers the iris, can alter the image of the iris somewhat as it changes in shape. Cataract surgery can also cause the iris to change dramatically, at least temporarily.

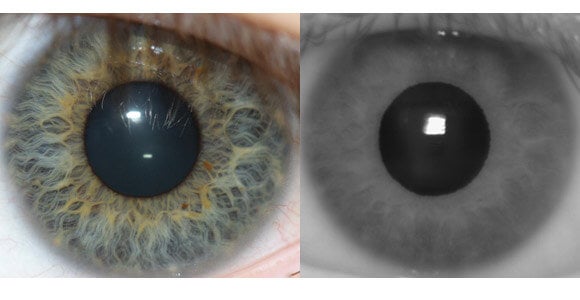

Colored contacts, however, won’t fool the scanners, which rely on pattern recognition that looks beyond color.

Even with the vote of confidence from NIST, iris scans will continue to compete to become the dominant basis for biometric identification with systems that focus on anatomical quirks including fingerprints, facial and voice recognition.

Images: Smhossei via Wikimedia Commons, NIST, Department of Defense via Wikimedia Commons