A promising new approach to treating cancer involves removing some of the patient’s immune T cells and reprogramming them so that they can successfully destroy cancer cells. The modified cells are cultivated in the lab before being re-introduced into the patient to grow their ranks and kill off cancer.

For patients with end-stage cancer, the fact that it costs quite a bit of money to grow cells in a lab may not matter much. But for doctors looking for an approach that will work for more patients in more hospitals, it does.

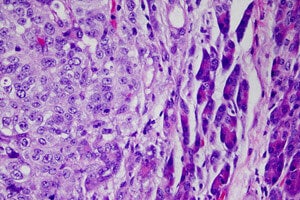

A diverse team of Boston-based doctors and scientists has developed an approach that lets the patient’s own body serve as a bioreactor to nurture a powerful immune reaction to melanoma, the deadliest form of skin cancer.

The treatment recently began a two-year clinical trial on 25 patients at the Dana-Farber Cancer Center after it resulted in a 90 percent survival rate in an earlier study on mice with otherwise fatal cancer. Half of the mice showed no signs of cancer at all after being treated with the vaccine.

The treatment recently began a two-year clinical trial on 25 patients at the Dana-Farber Cancer Center after it resulted in a 90 percent survival rate in an earlier study on mice with otherwise fatal cancer. Half of the mice showed no signs of cancer at all after being treated with the vaccine.

Doctors insert an aspirin-sized sponge, which consists of polymers, just under the skin. By mimicking infection, the materials in the sponge signal immune cells to come to it. The device then supercharges the cells before sending them out to find and kill cancer.

“We’re trying to take the biology that normally happens in a lab and instead move it into the human body, and it’s all orchestrated by these little pieces of plastic. It looks like it might be more powerful than the traditional way of pursuing cancer vaccines and it clearly could be much less expensive and much less of a regulatory burden as well,” said David Mooney, a Harvard professor of bioengineering who is part of the cross-disciplinary team that developed the implant.

The vaccine specifically works by stimulating dendritic cells to teach the rest of the immune system to recognize cancer as an invader and mount a counter-attack.

Other promising vaccines have used stem cells to supply the patient with more T cells and altered the shape of the T cells to enable them to skewer cancer cells. Another put together immune cells and cancer cells marked with a protein to make them easier to recognize as a threat in order to train the patient’s immune cells before reintroducing them.

Other promising vaccines have used stem cells to supply the patient with more T cells and altered the shape of the T cells to enable them to skewer cancer cells. Another put together immune cells and cancer cells marked with a protein to make them easier to recognize as a threat in order to train the patient’s immune cells before reintroducing them.

The Phase I trial is intended primarily to determine whether the vaccine is safe for humans. But because all of participants suffer from late-stage melanoma, researchers also expect to get some “very limited data” on how well the method works, Mooney told Singularity Hub.

If the implant proves safe, the researchers are poised to modify it for use against other types of cancer as well.

Images: Mataj Kastelic via Shutterstock.com; vaccine courtesy Dana-Farber Cancer Center; melanoma cells by Richard Lee National Cancer Institute via Wikimedia Commons