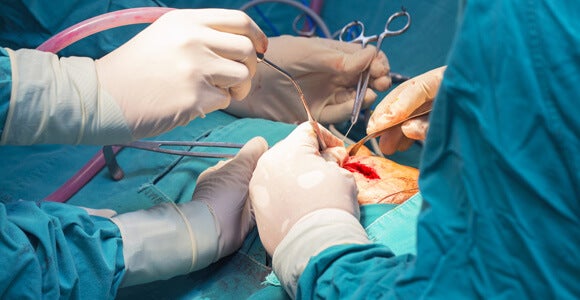

Hands-free devices like Google Glass can be really transformative when the hands they free are those of a surgeon. And leading hospitals, including Stanford and the University of California at San Francisco, are beginning to use Glass in the operating room.

In October, UCSF’s Pierre Theodore, a cardiothoracic surgeon, became the first doctor in the United States to obtain Institutional Review Board approval to use the device to assist him during surgery. Theodore pre-loads onto Glass the scans of images of the patient taken just before surgery and consults them during the operation.

“To be able to have those X-rays directly in your field without having to leave the operating room or to log on to another system elsewhere, or to turn yourself away from the patient in order to divert your attention, is very helpful in terms of maintaining your attention where it should be, which is on the patient 100 percent of the time,” said Theodore.

Theodore has performed a dozen surgeries using Google Glass. But before UCSF surgeons could access images in the operating room using Glass, they had to manually load the images after manually scrubbing them of personal information, so that they could transmit them over Wi-Fi without breaking confidentiality laws.

Theodore has performed a dozen surgeries using Google Glass. But before UCSF surgeons could access images in the operating room using Glass, they had to manually load the images after manually scrubbing them of personal information, so that they could transmit them over Wi-Fi without breaking confidentiality laws.

A Stanford-affiliated startup called VitalMedicals is developing a system that would automate doctors’ access to patient images and medical records using Glass by syncing them automatically via Wi-Fi. VitalMedicals’ debut app, VitalStream, sends live vital signs and alarms to the operating surgeon’s Glass device during conscious sedation. It gets the vital signs from its integration with the ViSi mobile vital sign monitor, which Singularity Hub also recently covered.

VitalMedicals is working on a second app, SurgStream, which displays the pre-surgical images and streams live fluoroscopy, ultrasound and endoscopy video to Glass or a tablet.

Surgeons do already have access to patient images, but they must sometimes peer behind other monitors or re-scrub after touching files or devices. The voice-activated Google Glass makes it that much easier for surgeons to consult those materials in the course of the procedure.

While average users might find Glass’s tiny display tiring to look at, surgeons are already accustomed to looking through magnifying glasses while they work.

While average users might find Glass’s tiny display tiring to look at, surgeons are already accustomed to looking through magnifying glasses while they work.

“If you believe in the fundamental assumption that having accurate data in the hands of the clinician leads to better decision-making, then it would seem to me that having that data in a way that’s convenient, comfortable and always present in the presence of the patient can lead to greater efficiencies and better decision-making overall,” Theodore said.

Before Glass can be widely used in operating rooms, the syncing that UCSF did by hand will have to be reliably automated. Images and patient records will have to be stripped of all potential identifying information to avoid breaches of privacy. And Wi-Fi connections will have to be assured in a difficult environment: The medical equipment in an operating room often interferes with Wi-Fi signals.

The projects, which emerged from Google’s early outreach to developers to create apps for Glass, are still in their earliest stages and still have time to iron out the bugs. But with many doctors interested in applications for the wearable interface, Glass is likely to spread quickly in ORs when they do.

Images: adirekjob via Shutterstock.com, UCSF, lasalus via Shutterstock.com