Stem cells promise bright new frontiers in medicine: Doctors can already study patients’ unique disease manifestations without biopsies thanks to the cells, and one day they hope to use them to spur patients to grow healthy new cells to restore or replace diseased body parts.

Recognizing their revolutionary potential, the Nobel committee awarded the 2012 Nobel Prize in medicine to Shinya Yamanaka and others who made it possible to obtain stem cells by mixing foreign DNA with an adult patient’s cells to create an ersatz embryo. (Cells created using this method are called induced pluripotent stem cells, or iPSCs.)

But new research has found a way to develop the malleable stem cells using a simpler and potentially cheaper method. In a paper published in Nature, researchers from Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Japan’s RIKEN Center show that by simply giving an adult cell an acid bath, they can convert it into a stem cell.

“Our research findings demonstrate that creation of a stem cell from an individual that has the potential to be used for a therapeutic purpose without an embryo is possible,” said senior author Charles Vacanti, director of the Laboratory for Tissue Engineering and Regenerative Medicine at Brigham and Women’s Hospital.

The startlingly simple method was inspired by the researchers’ observations of plant behavior. Injured plant cells create a callus that can develop into a new plant, prompting the researchers to wonder if animal cells might have the same response. In the experiment, they took mature mouse white blood cells and stressed them almost to the point of death. Within a few days, the cells had recovered by reverting into a state of newborn potential like that heralded in embryonic stem cells.

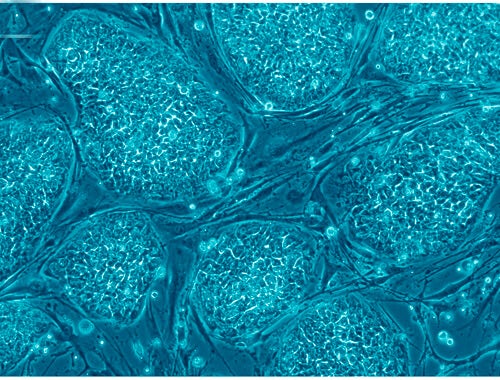

They then put the cells — which they call STAP, or stimulus-triggered acquisition of pluripotency, cells — back into live mice, and confirmed that they specialized and spready throughout the body (pictured).

They then put the cells — which they call STAP, or stimulus-triggered acquisition of pluripotency, cells — back into live mice, and confirmed that they specialized and spready throughout the body (pictured).

“Our findings suggest that somehow, through part of a natural repair process, mature cells turn off some of the epigenetic controls that inhibit expression of certain nuclear genes that result in differentiation,” said Vacanti.

Lorenz Studer, a developmental biologist at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center who was not involved in the study, told Singularity Hub the findings could represent a breakthrough in stem cell-based medicine.

But “like every really truly breakthrough study, it raises more questions than it answers,” he said.

The major question is whether the process will work as well with human cells as it did with mouse cells, and whether it will work using types of cells that doctors can easily harvest from patients of all ages. Studer also noted that the exact properties of the STAP cells aren’t really evident from the early findings.

If the method does work with human cells, it will have major clinical implications. Yamanaka’s method of creating stem cells is expensive and inefficient — just one percent of cells that undergo the 20-day process become iSPCs. These bottlenecks limit research in the field, and a major improvement to any one could make STAP the new clinical norm, Studer said.

One thing is for sure: With a process this simple and important, many labs are going to be trying it using human cells, so answers should be forthcoming soon.

Photos: Nissim Benvenisty via Wikimedia Commons; Charles Vacanti courtesy Nature

Note: Since this article was published, some scientists have challenged the validity of the STAP study based on their inability to reproduce the results, and the RIKEN Center has launched an internal investigation. The authors have withdrawn the paper while the questions are addressed.