Link Between Mom’s Diet at Conception and Child’s Lifelong Health, Study Reveals

The mother’s nutrition at the time of conception can permanently and fundamentally affect physical characteristics of her offspring, according to a study just published in Nature Communications, by influencing the child's epigenome.

Share

There’s an imposing volume of research that shows that children raised in poverty are more likely to have lousy health outcomes. But while many studies have tried to nail down what exactly about poverty causes each of the diseases for which children’s risks are elevated, those answers remain elusive.

A study just published in Nature Communications points to a previously unknown mechanism: Researchers linked inadequate nutrition in the mother at and just prior to conception with particular changes in the children’s epigenome, which controls how a person's genes are expressed over his or her lifetime.

The mother’s nutrition at the time of conception can permanently and fundamentally affect physical characteristics of her offspring, according to the study.

"Our results represent the first demonstration in humans that a mother's nutritional well-being at the time of conception can change how her child's genes will be interpreted, with a life-long impact,” senior author Branwen Hennig said in a news release.

The study took advantage of a control group provided by nature itself: the rainy season. In the Gambia, the rainy season is often called the hungry season; the dry season, by contrast, is when the harvest takes place. So researchers from the Gambia Unit of the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine compared babies conceived at the peak of the rainy season with those conceived at the peak of the harvest season.

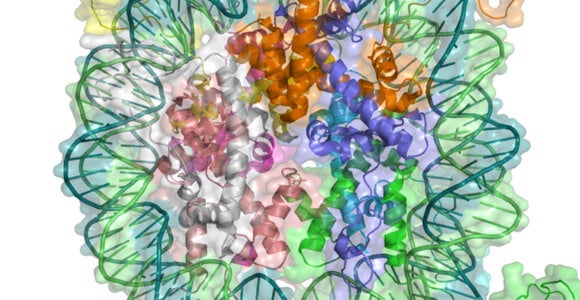

Children conceived during the “hungry” season had more DNA methylation than those conceived during the harvest season. DNA methylation is most often credited with silencing genes, though in some cases it can activate them.

The study does not address what specific consequences methylation will be for the infants, but it documents for the first time that methylation at specific sites, called metastable epialleles, can produce permanent physical differences even given identical genes. It builds on observations of genetically identical lab mice whose coats nonetheless varied in color.

In fact, the researchers can't yet say whether methylation at the studied sites is good or bad, but only that, through it, maternal nutrition at the time of conception can have permanent, pervasive effects on the child's health.

“Overall what this shows is that mom’s nutrition around the time of conception can determine whether her baby will have more or less epigenetic dysregulation, and our hunch is that it’s that dysregulation overall which will prove to be deleterious,” co-author Rob Waterland, a professor of pediatrics and genetics at Baylor College of Medicine, told Singularity Hub.

Be Part of the Future

Sign up to receive top stories about groundbreaking technologies and visionary thinkers from SingularityHub.

Already pushing to answer some of those questions, the researchers said the work will ultimately most likely point mothers-to-be toward an overall balance of nutrients rather than a few specific supplements. The two strongest nutritional correlations indicate that higher levels of the metabolites homocysteine and cysteine in the mother's blood correlate with less methylation in the child's DNA.

“Our on-going research is yielding strong indications that the methylation machinery can be disrupted by nutrient deficiencies and that this can lead to disease. Our ultimate goal is to define an optimal diet for mothers-to-be that would prevent defects in the methylation process … [O]ur research is pointing towards the need for a cocktail of nutrients, which could come from the diet or from supplements,” said Andrew Prentice, another of the authors.

The study also indicates that the mother's weight influenced the child's gene regulation. Of the 167 women in the study, those with higher body-mass indexes, or BMIs, generally had babies with less DNA methylation. Among the study population of rural Gambian women, higher BMI indicated that the women were better nourished, not that they were obese.

Still, if maternal weight affects how a child’s genes express over his or her lifetime, it could be that, in developed countries, maternal obesity saddles children with the effects of epigenetic dysregulation.

“There’s a lot of interest in the idea that maternal obesity could promote obesity in her children, and epigenetics could be one potential mechanism for this to happen,” Waterland explained.

Whatever the specifics turn out to be, it's clear that it's important for women in poor countries and rich alike to get quality nutrition in their child-bearing years.

Images: Richard Wheeler via Wikimedia Commons; Felicia Webb

Cameron received degrees in Comparative Literature from Princeton and Cornell universities. He has worked at Mother Jones, SFGate and IDG News Service and been published in California Lawyer and SF Weekly. He lives, predictably, in SF.

Related Articles

Single Injection Transforms the Immune System Into a Cancer-Killing Machine

This Light-Powered AI Chip Is 100x Faster Than a Top Nvidia GPU

This Week’s Awesome Tech Stories From Around the Web (Through December 20)

What we’re reading