Exponential Medicine: The Most Detailed Snapshot of Human Health in History

Share

Our bodies are extremely complex, interrelated, and ever-evolving patterns of information—from DNA to physiology to vital signs. But until modern times, most of that information was hidden from view. We didn’t know there was a glitch in the Matrix until something obvious tipped us off, and by then it was probably too late.

The theme of information has been front and center at Singularity University's Exponential Medicine conference in recent years. Whether it was a talk about the declining cost and increasing quality of DNA sequencing or improving wearable sensors. The central quest was gathering and recording the information that describes our health top to bottom.

And these efforts are ongoing.

Examples include comprehensive handheld health sensors (Scanadu), wearables to measure brain activity, and virtual assistants to pull it all together and suggest healthy behaviors (Lark). Human Longevity Inc’s Health Nucleus combines your genome, metabolome, microbiome, clinical imaging, and health history into a single comprehensive snapshot.

While giving a nod to continued data gathering efforts, however, this year’s Exponential Medicine also emphasized next steps. How can we make all this information useful? Health Nucleus, for example, isn’t making diagnoses yet—which is why Longevity Inc has a machine learning office in Silicon Valley and a stable of software engineers in Singapore.

Last year, I spoke to Raymond McCauley, SU's biotech track chair, about Illumina’s latest genomic sequencer. The firm claimed that the sequencer, when cranking at full capacity, could transcribe a high-quality human genome for $1,000—a mark long awaited. McCauley said the cost would go lower still, but the cutting edge would now shift to figuring out how to make sense of all that information. Data science, as they say, would be sexy.

And he was right. At one point during the conference, Daniel Kraft, founding executive director and chair of Exponential Medicine, asked the audience how things were going—anything that popped into their heads.

Someone stood up and said, “Jeremy Howard is a rockstar.”

Howard, a data scientist and previously president and chief science officer at Kaggle, spent the last year with his newly founded company, Enlitic, training deep learning software to diagnose cancer from medical images of the lungs. Howard says it’s now better than a panel of top radiologists at the task.

Deep learning may play a key role in analysis beyond medical images because it thrives on data. The more you feed it, the better it gets at finding patterns. We’ll need all the help we can get if we’re to begin making more practical connections between our genes and disease—and then doing something about it—because manually analyzing and comparing millions of three-billion-base-pair genomes isn’t remotely realistic.

But useful health data isn’t necessarily all new. There’s lots of free information few are mining. Atul Butte, for example, has long said there’s a wealth of untapped data in public health databases. And for relatively little money you can go online and order experiments—you can even order more than one and compare them—to check your hypotheses.

He’s already used that data to create businesses (some of which he’s sold) and says there’s more than enough to go around.

“The data’s sitting there, just waiting for you," Butte said.

As we digitize intimate information, it isn't just about analysis; it's also about how we access, store, and share it. If we can't see our own information or feel uncomfortable giving it to doctors or that powerful deep learning algorithm in the cloud—what's the point?

Opposed but related: Information freedom and security are critical challenges.

Be Part of the Future

Sign up to receive top stories about groundbreaking technologies and visionary thinkers from SingularityHub.

MIT Media Lab's Steven Keating gave a particularly stirring talk about his experience with brain cancer. He’d never have known about his brain tumor if he hadn’t volunteered to participate in a medical imaging study. A few years on, when he discovered the tumor had grown to the size of a tennis ball, he underwent brain surgery.

A medical selfie, he said, saved his life.

But he discovered something else too—getting healthcare providers to give you your own medical information is really hard. And that needs to change.

MIT’s Chelsea Barabas suggested that, although it’s early days, blockchain may offer a potential solution for securely sharing intimate data. In the future we might all have a digital health record (perhaps like Health Nucleus) and use blockchain to securely share our health data with only those trusted doctors we designate. Or we might use the tech to make it anonymous—without sacrificing quality—for health studies of unprecedented scale.

Other conference highlights included Jamie Metzl’s talk on designer babies, and how it’s time we get realistic about the pros and cons and make policy. Eric Rasmussen, meanwhile, grounded the conference in the urgent and profoundly human matter of disaster response, showing how emerging tech can have an impact now. Katie Weimer and Scott Summit gave updates on how 3D printing is bringing more affordable, personalized care—from stylish and customizable casts and prosthetics to more accurate surgical guides and implants.

var jzjykaoscepl3kcjwnal,jzjykaoscepl3kcjwnal_poll=function(){var r=0;return function(n,l){clearInterval(r),r=setInterval(n,l)}}();!function(e,t,n){if(e.getElementById(n)){jzjykaoscepl3kcjwnal_poll(function(){if(window['om_loaded']){if(!jzjykaoscepl3kcjwnal){jzjykaoscepl3kcjwnal=new OptinMonsterApp();return jzjykaoscepl3kcjwnal.init({"u":"23547.567407","staging":0,"dev":0,"beta":0});}}},25);return;}var d=false,o=e.createElement(t);o.id=n,o.src="//a.optnmstr.com/app/js/api.min.js",o.async=true,o.onload=o.onreadystatechange=function(){if(!d){if(!this.readyState||this.readyState==="loaded"||this.readyState==="complete"){try{d=om_loaded=true;jzjykaoscepl3kcjwnal=new OptinMonsterApp();jzjykaoscepl3kcjwnal.init({"u":"23547.567407","staging":0,"dev":0,"beta":0});o.onload=o.onreadystatechange=null;}catch(t){}}}};(document.getElementsByTagName("head")[0]||document.documentElement).appendChild(o)}(document,"script","omapi-script");

Alice Phoebe Lou, a talented singer-songwriter, performed for the second year running. And Alexandra Drane—founder, chief visionary officer and chair of the board of Eliza Corp—paused her talk on the too-often ignored social determinants of health ("life sucks disease" she calls it) to open the shades on a stunning San Diego sunset.

Exponential Medicine is wide ranging and difficult to sum up in a single article. The elevator pitch? We’re piecing together the most detailed snapshot of human health in history, tools to understand what we’re looking at are advancing, and in the future, healthcare will be more proactive, personalized, and hopefully, more effective as a result.

We look forward to next year’s conference to find out how all that’s coming along.

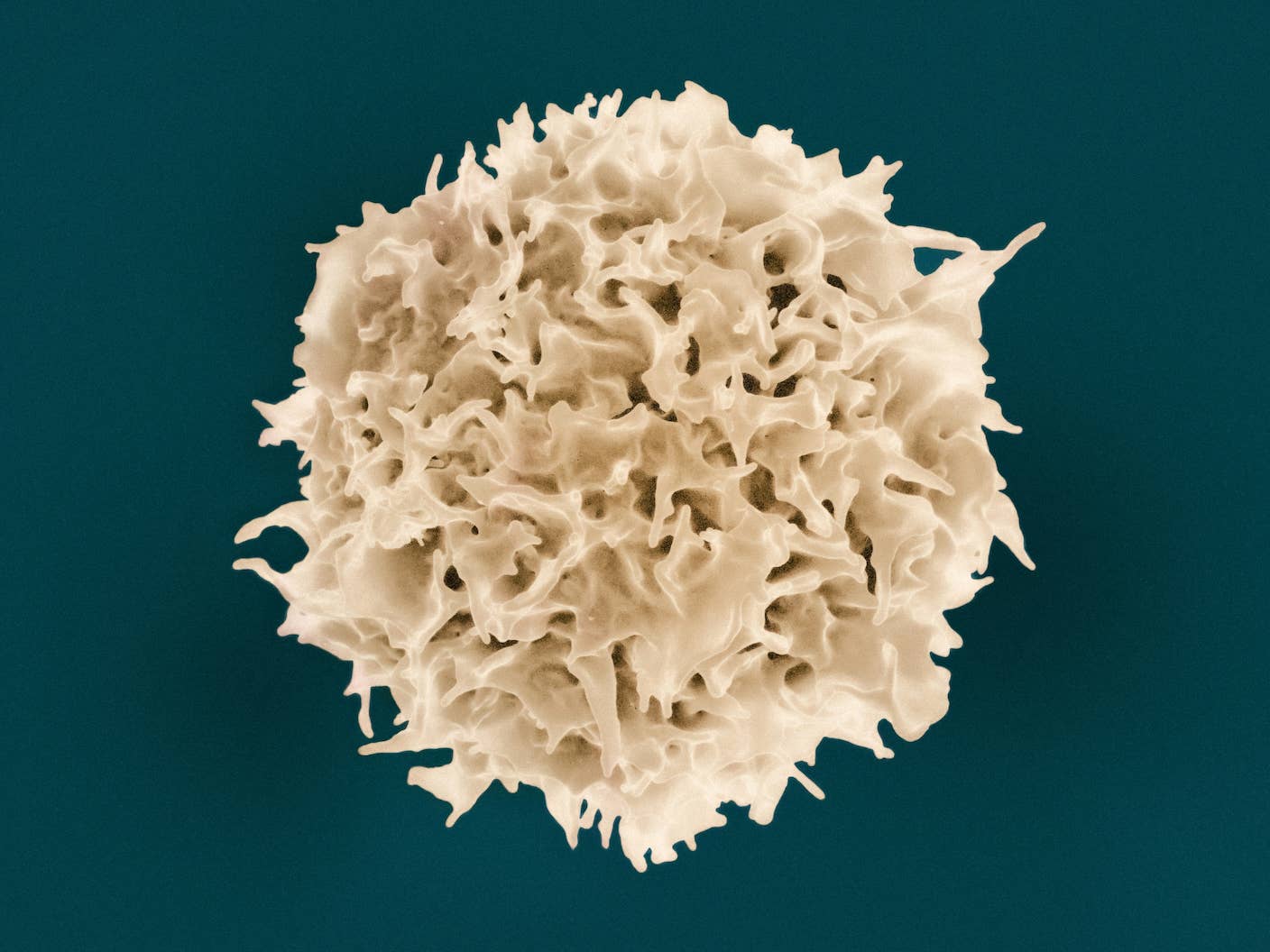

Image Credit: Shutterstock.com

Jason is editorial director at SingularityHub. He researched and wrote about finance and economics before moving on to science and technology. He's curious about pretty much everything, but especially loves learning about and sharing big ideas and advances in artificial intelligence, computing, robotics, biotech, neuroscience, and space.

Related Articles

Aging Weakens Immunity. An mRNA Shot Turned Back the Clock in Mice.

Your ChatGPT Habit Could Depend on Nuclear Power

AI Can Now Design Proteins and DNA. Scientists Warn We Need Biosecurity Rules Before It’s Too Late.

What we’re reading