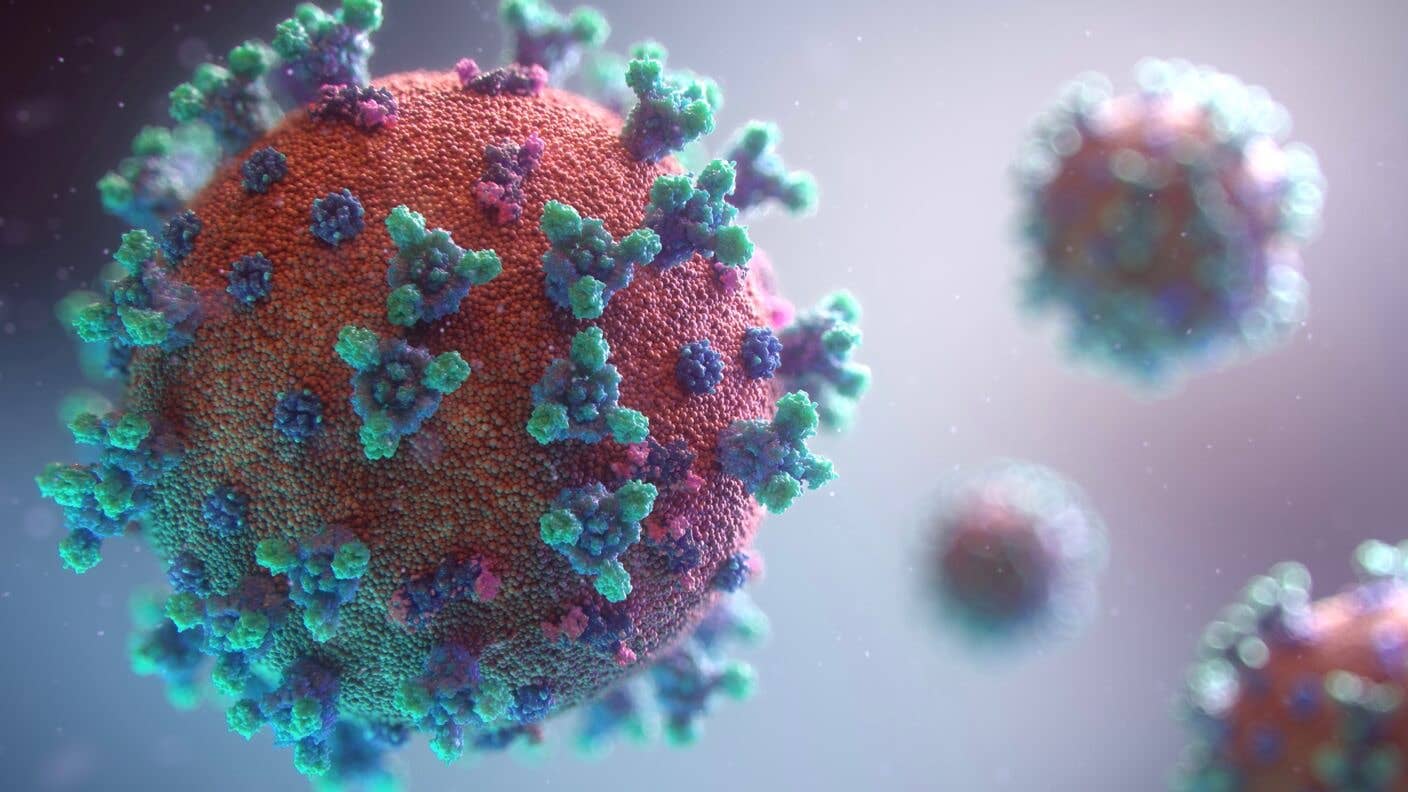

Can Genes Explain Why Coronavirus Seriously Sickens Some and Spares Others?

Share

In the early 1980s, a deadly epidemic was gaining momentum. Caused by a virus dubbed HIV, AIDs has since infected and killed millions of people around the world. But not everyone who is exposed to HIV gets sick. In the mid-90s, researchers found that a variation of a gene called CCR5 made some people resistant to the virus.

When it comes to how viral infections interact with our bodies, genes matter.

Now, scientists are turning to DNA to solve a mystery at the heart of the Covid-19 pandemic. Why do some young and otherwise healthy people get gravely ill, while others have only mild symptoms or no symptoms at all? Might the answer be in our genes?

A host of studies aims to tap the genetic information of thousands of people to find out.

It’ll take time to tease answers from the data, and the story will have to account for the complicated dance of genes, body, environment, and behavior. But scientists hope new discoveries can help us identify those most at risk—even if they don’t seem it—better trace the disease’s course in the body, and more effectively treat patients.

A Covid-19 Mystery

From the earliest days of the pandemic, reports have noted Covid-19 was most severe for the elderly and ill. The CDC says there’s still not enough information to fully outline risk factors. But older people with pre-existing health conditions, including asthma and lung disease, cardiac disease, diabetes, and immune conditions are most at risk.

In the general population, however, there’s a wide range of how sick people get.

There are accounts of young and seemingly healthy people admitted to the ICU, while others—scientists don’t know how many yet—have no symptoms at all. There’s even some variation between the extremes. Some people get moderately sick with a dry cough, fever, fatigue, and shortness of breath. Some lose their sense of taste. Others have diarrhea.

Epidemiologists are already digging through a trove of information to better understand the disease. How do demographics, behavior, medications, or availability of care affect outcomes? Answers to these questions will likely be most helpful in coming weeks and months, just as soap, water, communication, and planning are our most effective short-term weapons for halting the virus's spread.

New capabilities—maybe for this pandemic, maybe the next one—are emerging too though. While studies into how genes bend the course of a disease would have once taken years, we’re nearing a time when they can yield answers faster to bring more targeted care.

But first, how might DNA play a role in how sick Covid-19 makes people?

Viruses Pick Cellular Locks. Some Genes Rekey Them.

Viruses break into our cells and commandeer cellular machinery to reproduce. Like a thief who’s copied the key to your front door, they carry proteins that fit complementary “receptor” proteins on a cell’s surface. If there’s a match, presto, they’re in.

The CCR5 mutation, for example, codes for a variant of the surface protein HIV uses to invade immune cells. As the key no longer fits the lock, the virus is left out in the cold. Unable to replicate on its own, it can’t spread. The would-be invasion hits a wall.

The virus behind Covid-19 also uses a protein receptor, ACE2, to enter respiratory cells. It may be that some people’s genes produce protein “locks” that are harder for Covid-19 to pick, or that regulatory genes are slowing the production of ACE2. Depending on our DNA, then, some of us may have cells that are more open to infection—and so suffer more serious illness—while others offer fewer viral targets and escape relatively unscathed.

Another possibility is that genetic variants are tuning our immune systems differently. Perhaps it’s a combination, or some other cog in the machine still waiting to be discovered.

At the moment, we just don’t know.

Be Part of the Future

Sign up to receive top stories about groundbreaking technologies and visionary thinkers from SingularityHub.

But We Do Have Lots of DNA to Sift

Mainstream genetic testing and whole genome sequencing are tools we haven’t had in the past. Not long ago, DNA testing kits for ancestry or general health were some of the most popular holiday gifts. Meanwhile, the cost of sequencing a whole human genome has been at or under $1,000 for years, leading to a number of very large sequencing projects.

In the former case, companies like 23andMe have assembled huge DNA databases. Though such tests look at only a fraction of a genome—using a process called genotyping—23andMe has the genetic data of over 10 million people on file. Eighty percent of these have authorized the company to use their data for research, and to that end, they recently sent customers a survey to collect information for a potential Covid-19 study.

If they get enough responses, they’ll combine survey answers with each person’s genetic profile and conduct a genome-wide association study to link genetic similarities and differences to particular traits and outcomes. This approach would most likely find common gene variants shared by many people, but it may miss less common variants that more complete gene sequences would capture. And such rarities may be key, according to Stephen Chapman, a University of Oxford respiratory physician and researcher.

This is where collections of more complete genomic data may prove powerful.

Many such studies already exist, and new ones are popping up. To gather the work under one banner, the University of Helsinki’s Andrea Ganna and Mark Daly started the Covid-19 Host Genetics Initiative. Over 100 studies are participating in the project, according to their site, and a dozen large biobanks have shown interest.

“There are long-standing studies, involving hundreds of thousands of people, and other smaller ones collecting data on patients who test positive," Ganna told the BBC. "It’s such a huge diversity and there are a lot of countries involved, and we will try to centralize it.”

The UK Biobank is an example of one of those bigger existing studies.

The biobank has biological samples and health information for 500,000 people and plans to collect and add Covid-19 information to the database. Over 15,000 scientists have access to the data. Similarly, DeCODE Genetics, an Icelandic company, has the genetic and health data of over half of Iceland's population and is also testing people for Covid-19.

The Personal Genome Project, founded in 2005 by Harvard’s George Church, is hoping to add Covid-19 data from thousands of participants to its database too. And a team led by Jean-Laurent Casanova, a Rockefeller University professor, will tap sequencing hubs around the world to record the genomes of young, healthy patients sent to the ICU with Covid-19.

It’s unclear what these projects will find, or how long it will take. What is clear is that large collections of genetic and health information are making it possible to quickly begin serious genetic studies of the disease—sometimes with little more needed than a new survey.

Scientists have never so willingly shared information or singularly focused on one problem. Add to that a flood of clinical and scientific information gathering and a digital highway to deliver it worldwide, and you have the recipe for scientific collaboration of epic proportions.

We’ll know more tomorrow, in two weeks, and in two months than we do today. Faced with so much uncertainty, that’s a hopeful thought.

Image Credit: Fusion Medical Animation / Unsplash

Jason is editorial director at SingularityHub. He researched and wrote about finance and economics before moving on to science and technology. He's curious about pretty much everything, but especially loves learning about and sharing big ideas and advances in artificial intelligence, computing, robotics, biotech, neuroscience, and space.

Related Articles

Single Injection Transforms the Immune System Into a Cancer-Killing Machine

This Light-Powered AI Chip Is 100x Faster Than a Top Nvidia GPU

This Week’s Awesome Tech Stories From Around the Web (Through December 20)

What we’re reading