A $500 Million International Project Will Create the Most Detailed Map of the Brain Ever

Share

Despite decades of research, the human brain remains largely a mystery to science. A new $500 million project to create the most comprehensive map of it ever could help change that.

Our brains are among the most complex objects in the known universe. Deciphering how they work could bring tremendous benefits, from finding ways to treat brain diseases and neurological disorders to inspiring new forms of machine intelligence.

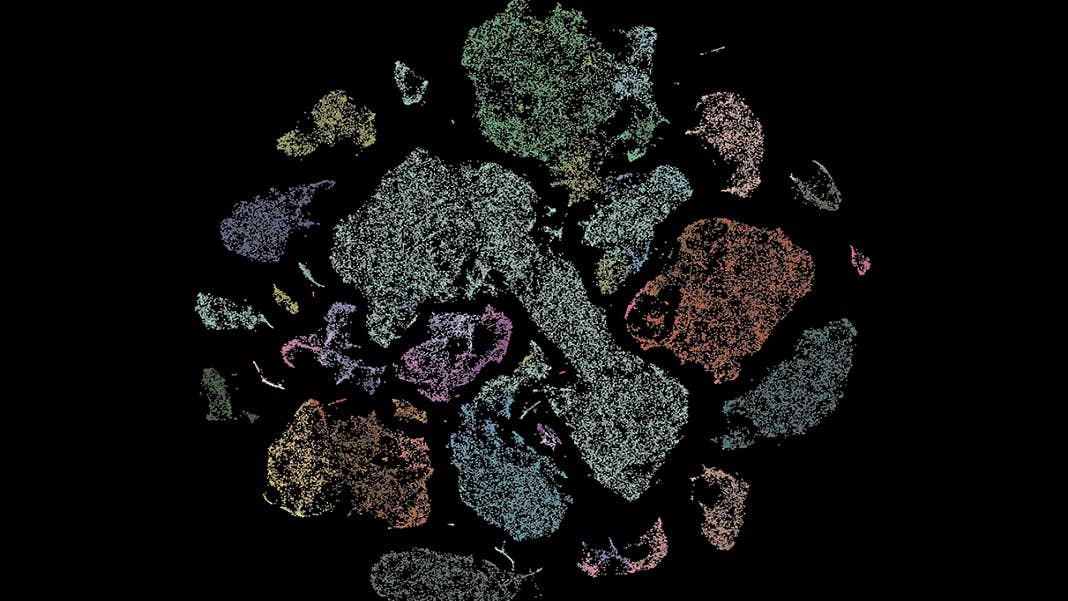

But a critical starting point is coming up with a parts list. While everyone knows that brains are primarily made up of neurons, there are a dazzling array of different types of these cells. That’s not to mention the various kinds of glial cells that make up the connective tissue of the brain and play a crucial supporting role.

That’s why the National Institutes of Health’s BRAIN Initiative has just announced $500 million in funding over five years for an effort to characterize and map neuronal and other types of cells across the entire human brain. The project will be spearheaded by the Allen Institute in Seattle, but involves collaborations across 17 other institutions in the US, Europe, and Japan.

“These awards will enable researchers to explore the multifaceted characteristics of the more than 200 billion neurons and non-neuronal cells in the human brain at unprecedented detail and scale,” John Ngai, director of the NIH BRAIN Initiative, said in a statement.

The BRAIN initiative was launched in 2014 by former president Barack Obama to revolutionize our understanding of the human brain. The new project builds on a previous effort to identify and map more than 100 cell types across the motor cortex of a mouse, and will borrow many of the tools and techniques developed for that effort.

These include approaches like single-cell transcriptomics, which make it possible to measure the gene expression of individual cells, and spatial transcriptomics, which make it possible to map gene expression over large sections of tissue and localize gene activity to specific regions.

A group from the Salk Institute in San Diego will also focus specifically on how the brain changes as we get older by measuring changes in gene expression over time—known as epigenetic changes—in brain samples from people of varying ages.

Be Part of the Future

Sign up to receive top stories about groundbreaking technologies and visionary thinkers from SingularityHub.

It will be an ambitious task, though. The human brain is 1,000 times larger than a mouse brain and far more complex, so scaling these techniques up won’t be a simple process. If they succeed, the resulting cell atlas will become a powerful and freely-accessible resource for neuroscientists all over the world.

“I really do view this as like the Human Genome Project. We have the ability now to define cells like we were able to define genes,” Ed Lein, who is leading the Allen Institute’s contribution, told STAT. “This is the foundation to start to understand a lot of other aspects of biology and disease.”

These projects are part of a new round of funding dubbed BRAIN 2.0 that was launched at the start of this year. Alongside the scaling up of efforts to map out different kinds of brain cells, $36 million will go towards an initiative called the Armamentarium for Precision Brain Cell Access, which will use data on brain cell types to develop new tools designed to target them for study and potentially treatment.

And there’s more funding to come. Early next year, the NIH will dole out another $30 million to projects seeking to take the next step in mapping out the brain, moving on from the parts list to working out the wiring diagrams that govern how different cells and regions are connected.

With the project expected to generate petabytes of data, it’s likely to be years before scientists are able to make full use of this new resource. But it could prove to be a critical piece of the puzzle as we try and unravel the mysteries of the human brain.

Image Credit: Allen Institute

Related Articles

This Brain Pattern Could Signal the Moment Consciousness Slips Away

Vast ‘Blobs’ of Rock Have Stabilized Earth’s Magnetic Field for Hundreds of Millions of Years

Your Genes Determine How Long You’ll Live Far More Than Previously Thought

What we’re reading