Evidence Mounts for Gene Therapy as Treatment for Heart Failure

Damage done to the vital organ by heart failure has been the focus of much research into gene therapy, a process in which patients receive, usually inside an inert virus, replacement genes for those suspected of causing an illness. One genetic treatment has gotten as far as clinical trials in patients with heart failure, and initial results presented recently at an American Heart Association meeting, suggest that the gene therapy may just help hearts damaged by heart failure heal themselves.

Share

Doctors are quite good at bringing patients back from the swelling and exhaustion of heart failure, which affects nearly 30 million people worldwide. But there’s little they can do with conventional approaches to repair the damage done to their hearts.

That's why heart failure has been the focus of much research into gene therapy, a process in which patients receive, usually inside an inert virus, replacement genes for those suspected of causing an illness.

One genetic treatment has gotten as far as clinical trials in patients with heart failure, and initial results presented recently at an American Heart Association meeting, suggest that the gene therapy may just help hearts damaged by heart failure heal themselves.

The genetic approach, pioneered by Roger Hajjar at Mt. Sinai and commercialized by a company he co-founded, introduces the SERCA2 gene. In results shared in mid-November, Hajjar and his colleagues said that patients who received the gene experienced 80 percent fewer cardiovascular “events” than those who received a placebo.

Untreated, patients who have suffered heart failure have 50/50 odds of living more than five years.

But wait, there’s more: That’s how an infomercial might introduce Hajjar’s recent claim, in a paper also published in November, that a modification to the approach promises even better results. The paper argues that using the same technique to introduce a gene, called SUMO-1, that regulates the work of SERCA2 is more effective in large animals than introducing SERCA2 itself.

“SUMO-1 gene therapy may be one of the first treatments that can actually shrink enlarged hearts and significantly improve a damaged heart’s life-sustaining function,” Hajjar said in a news release.

Be Part of the Future

Sign up to receive top stories about groundbreaking technologies and visionary thinkers from SingularityHub.

Here’s the science behind the two linked approaches. SERCA2 produces an enzyme that allows cells to pump calcium out. In heart failure, SERCA2 is dysfunctional, forcing the heart to work harder and swell. The SUMO-1 gene, which regulates SERCA2’s activity, is also largely absent in failing human hearts.

The animal results compared SUMO-1 gene therapy, SERCA2 gene therapy and a combination of SUMO-1 and SERCA2. The delivery of high dose SUMO-1 alone, as well as SUMO-1 and SERCA2 together, resulted in stronger heart contractions, better blood flow, and reduced heart volumes, the researchers found.

Hajjar is seeking FDA approval to test the new therapy on humans and the SERCA2 therapy has qualified for an expedited approval process.

Gene therapy successes with heart failure come at a time that the approach appears to be recovering from earlier setbacks. Late last year, the European Union approved the first such medication. The Children's Hospital of Philadelphia spun out a company to usher some of its gene therapy drugs through the approval pipeline, clearly betting that the drugs will eventually be sold.

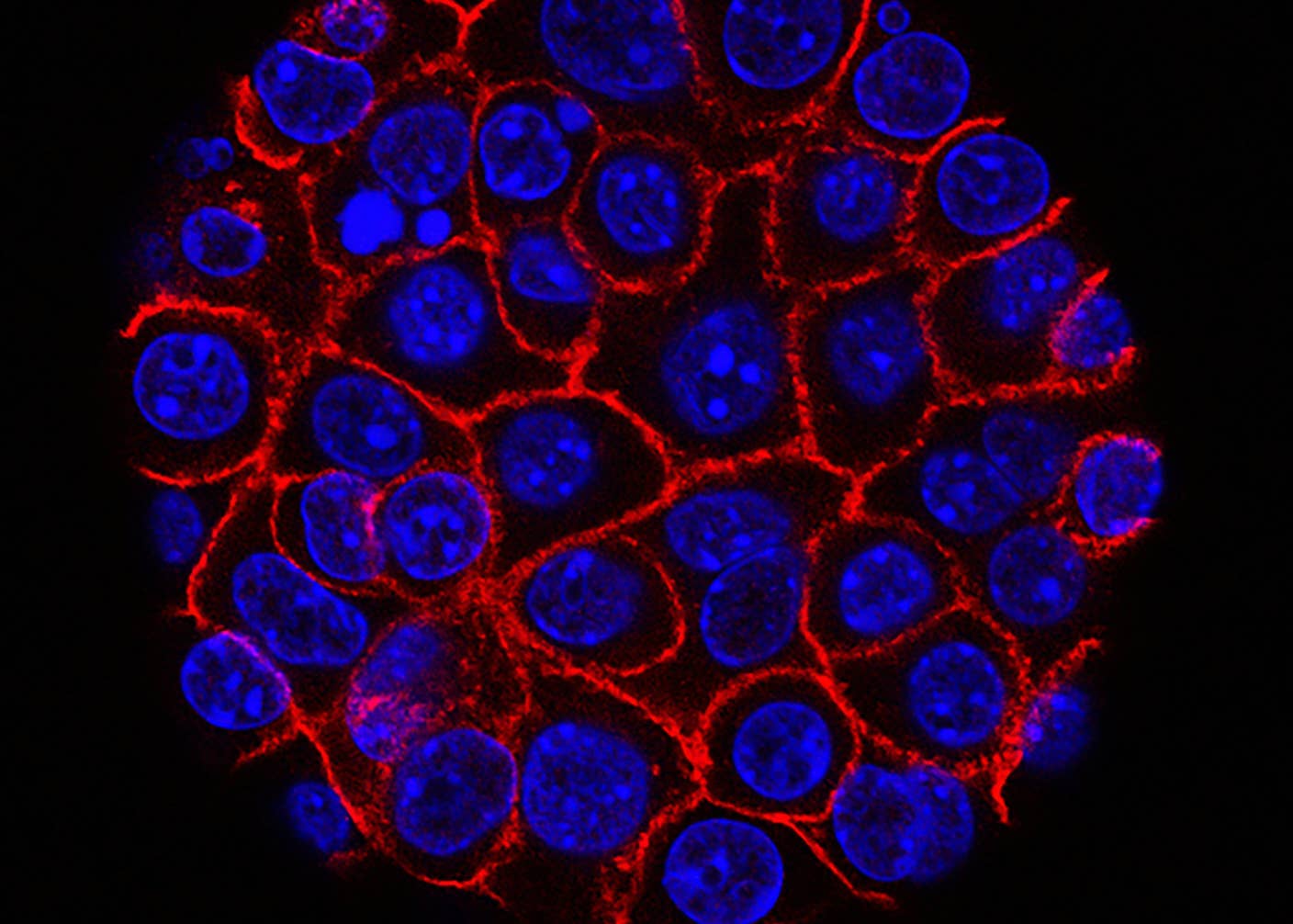

Meanwhile, other researchers are also investigating whether stem cells inserted into damaged hearts could develop into new, healthy tissue. One of the most promising approaches would use progenitor cells recovered from the patient’s bone marrow. But no stem cell treatments have yet gotten as far as human clinical trials.

Photos: BlueRingMedia and Mopic via Shutterstock.com

Cameron received degrees in Comparative Literature from Princeton and Cornell universities. He has worked at Mother Jones, SFGate and IDG News Service and been published in California Lawyer and SF Weekly. He lives, predictably, in SF.

Related Articles

Thousands of Everyday Drone Pilots Are Making a Google Street View From Above

These Supercharged Immune Cells Completely Eliminated Solid Tumors in Mice

New Device Detects Brain Waves in Mini Brains Mimicking Early Human Development

What we’re reading