Delivering Capsules of Stem Cells Helps Repair Injured Bones

Share

For the recorder of potentially breakthrough medical technology, sometimes it seems that the list is just so many applications of three new technologies: smaller electronics, new materials and stem cells. Any electronic device set up to function inside the body relies on smaller, flexible parts and new biocompatible casings, for example. Stem cells, properly manipulated, seem capable of mending nearly everything that ails us.

But the details of how best to cultivate certain kinds of cells and spur them to function in the body are still being worked out. According to University of Rochester researchers, materials science may be a big help.

One trouble with stem cells is that they don’t stay put. When doctors put cardiovascular progenitor cells in the heart to heal damage from a heart attack, the cells are whisked away in the bloodstream in a matter of hours.

Researchers, and a couple of renegade doctors in Colorado, have shown that stem cells do help bones heal. While bones, even the intricately shaped jawbone, have been grown in the lab, researchers have been somewhat stymied in their efforts at the seemingly more banal task of using stem cells and grafts to help heal major fractures, bones removed in surgery and other hard-to-fix injuries inside the body.

That’s where materials science comes in.

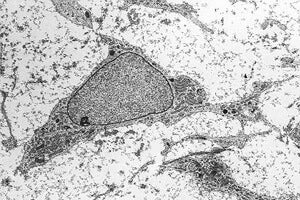

University of Rochester biomedical engineer Danielle Benoit encapsulated bone progenitor cells in a hydrogel wrapper and placed it on the bone she aimed to heal. Benoit hoped the wrapper would result in fewer stem cells being washed away and more sticking around to do the work of healing the bone. Others have used similar approaches to try to repair cartilage. (Nanomaterials have also been used to create new cartilage.)

Hydrogels are polymers that absorb water, and their texture is similar to that of bodily tissue. They are sometimes used to grow stem cells in the lab. But Benoit wanted to use them to grow cells in the body.

The pores in the gels Benoit used are smaller than cells, so the stem cells couldn’t escape. The wrappers were designed to dissolve in a couple of weeks — after the cells had begun their work but before the body identified them as interlopers and launched an immune attack.

It worked, Benoit recently reported in a biomaterials journal. As many new cells (tagged with fluorescence) remained at the site in a mouse as did in a petri dish, meaning that blood flow didn’t wash them away. And they managed to attach to the bone after the hydrogel wrapper dissolved.

Be Part of the Future

Sign up to receive top stories about groundbreaking technologies and visionary thinkers from SingularityHub.

If the wrappers work on human patients, they will mean that doctors can place stem cells very, very precisely in order to repair even the trickiest structures.

Because some tissues heal faster than others, Benoit demonstrated that different hydrogels that dissolve at different rates all worked.

“What we needed was a way to control how long the hydrogels remained at the site. Benoit said in a press release. “Our success opens the door for many — and more complicated — types of bone repair.”

Theoretically, the hydrogel wrapper could allow doctors to place stem cell seed bombs, if you will, anywhere in the body. Scientists at Emory University recently used a similar approach, but with a natural gel, to repair mouse hearts.

The first round of simply testing whether stem cells can help this or that problem (mostly they do), researchers may now turn to investigating how to make them work better.

Photos: Grzegorz Placzek / Shutterstock.com, Praisaeng / Shutterstock.com, Andrea via Wikimedia Commons

Cameron received degrees in Comparative Literature from Princeton and Cornell universities. He has worked at Mother Jones, SFGate and IDG News Service and been published in California Lawyer and SF Weekly. He lives, predictably, in SF.

Related Articles

Single Injection Transforms the Immune System Into a Cancer-Killing Machine

This Light-Powered AI Chip Is 100x Faster Than a Top Nvidia GPU

This Week’s Awesome Tech Stories From Around the Web (Through December 20)

What we’re reading